Scores of children among 128 dead in Russian sinking

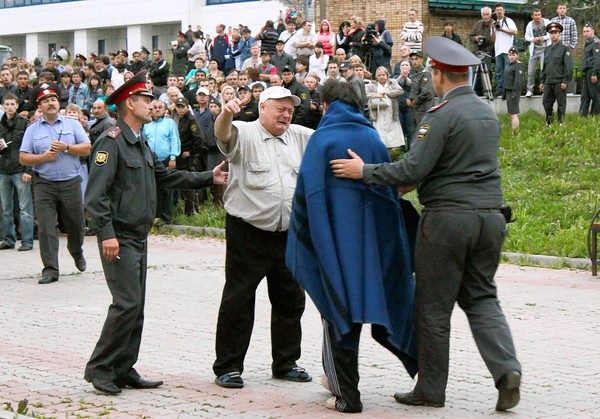

A relative greets a survivor in Kazan, Russia. (Tatarstan Emergencies Ministry / July 10, 2011)

When the cruise boat lurched on one side and then, slowly, capsized, the room became a sealed container. Adults broke windows with the heels of their shoes, or slid down the corridor and scrambled into the water. Meanwhile, babysitters managed to fasten life jackets on some of the children — there were 40 children, by some estimates. But they could not break out of the play room.

On Monday, divers were bringing the dead to the surface one by one. In all, 128 people were presumed drowned. It was the worst loss of life among children in Russia since 2004, when terrorists seized a school in the southern town of Beslan. Russian television showed rescued parents standing on a pier, screaming. “The child was left behind,” one man sobbed, wrapping his arms around a woman. “The child was left behind.”

As many as 208 people were on board when the boat sank, including at least 59 children. About 80 people were hauled out of the water about an hour and a half later, when the third of three passing vessels stopped to help.

Nikolai Laptev helped pull the survivors up, in shock and slick with diesel fuel, he told the newspaper Argumenty i Fakty. He could recall seeing only three children among them.

Authorities said the accident seemed to be the result of poor maintenance and a disregard for safety. Survivors said the 56-year-old boat was listing to the left even at port, which Russian maritime experts said was possibly because a sewage tank was overfull. Some passengers were so concerned by the tilt that they asked the captain to cancel the trip while docked at a port earlier Sunday, but the captain refused, Itar-Tass reported.

The boat suffered mechanical troubles that caused one of two engines to break down, according to the elite Investigative Committee,which is examining possible criminal misconduct. It was overburdened, carrying as many as 208 people when it was licensed to carry only 14o and crew. Twenty-three of the passengers were not registered.

It had last been overhauled in 1980, and its operators had no license to carry passengers, the Prosecutor General reported. Documents had been filled out sloppily — an official with the Emergency Situations Ministry told the RIA news agency that of the 59 children on board, 36 were listed as having been born on Dec. 30, 1999.

President Dmitri A. Medvedev convened his senior ministers on Monday at his residence outside Moscow.

“We have far too many old ships sailing our waters,” he said, according to a transcript on his Web site. “Just because up until now nothing had gone wrong did not mean that this kind of tragedy could not happen. It has happened now, and with the most terrible consequences.” Accounts by survivors and rescue officials suggest that the children had little chance of escape. Capt. Aleksandr Ostrovsky — whose own family happened to be aboard that day — was trying to turn the tilting, underpowered boat in the choppy water of a dammed portion of the Volga River that forms a broad lake, called the Kuybyshev Reservoir. Witnesses said they were almost two miles from the nearest shore.

As he turned, the captain exposed the boat’s length to waves, the news Web site Life News reported. One washed over the deck, sweeping some of the adults into the water, and the boat tilted.

“It just tipped to the right, flipped over, and sank,” Nikolai Chernov, one of the survivors, told Russian television.

“That was it,” he said. “There was no warning, nothing.”

Those who escaped had to fight their way out. Two dozen of the survivors picked up by the rescue ship, the Arabella, had lacerations and broken bones — caused by breaking the windows on their cabins and squeezing through, as the boat filled with water.

One passenger said her teenaged daughter had pulled out life jackets and thrust them at her parents. She said her husband cracked the window with his foot, and they were sucked out and fought their way to the surface — but their daughter never appeared. Natalya Makarova told state television that her daughter slipped from her hands as they tried to escape.

“We were all buried alive in the boat like in a metal coffin,” said Ms. Makarova, who escaped through a window. “I practically crawled up from the bottom. My 10-year-old child was with me, I held onto her as long as possible.”

Some survivors described moments of selflessness. Lilia Satarova, interviewed in a hospital in Kazan, said a man slammed against the glass window of her cabin until it broke — and then shoved her out first. “By then, we were already six feet underwater,” Ms. Satarova said.

The survivors spent an hour and a half in the water, clinging to debris and life vests. Two cargo barges passed without stopping, said Mr. Chernov. Another survivor told the Russia Today television station that passengers on one passing boat were taking cellphone videos of the people in the water.

Russian television showed survivors shaking with grief or staring hollowly at the port in Kazan where they were taken. In one, a woman yells, “My granddaughter, she was only five years old.”

On Monday, the first divers to examine the wreck at the bottom of the river said more than 100 bodies were inside, some of them wearing life preservers, a rescue official told Russian news agencies.

The name of the captain, Mr. Ostrovsky, was not among the list of rescued, and neither were the names of his wife and children, whom he had brought along on the trip.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Russian President congratulates Vietnamese Party leader during phone talks (January 25, 2026 | 09:58)

- Worldwide congratulations underscore confidence in Vietnam’s 14th Party Congress (January 23, 2026 | 09:02)

- Political parties, organisations, int’l friends send congratulations to 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:33)

- 14th National Party Congress: Japanese media highlight Vietnam’s growth targets (January 21, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th National Party Congress: Driving force for Vietnam to continue renewal, innovation, breakthroughs (January 21, 2026 | 09:42)

- Vietnam remains spiritual support for progressive forces: Colombian party leader (January 21, 2026 | 08:00)

- Int'l media provides large coverage of 14th National Party Congress's first working day (January 20, 2026 | 09:09)

- Vietnamese firms win top honours at ASEAN Digital Awards (January 16, 2026 | 16:45)

- ASEAN Digital Ministers' Meeting opens in Hanoi (January 15, 2026 | 15:33)

- ASEAN economies move up the global chip value chain (December 09, 2025 | 13:32)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version