The United States concluded CSPs with Vietnam in 2023 and Malaysia in 2025, both emphasising technology and semiconductor cooperation – a focus largely absent in earlier, trade-centred frameworks. Similarly, China’s CSPs with Malaysia (2013, 2024) and Thailand (2024) have evolved to include chip collaboration. This trend highlights how semiconductors have become a key marker of strategic trust and high-level alignment in the region.

ASEAN economies move up the global chip value chain

|

According to a report released by Hinrich Foundation on November 25, once peripheral players in assembly and testing, ASEAN economies are now emerging as strategic nodes in global chip production and investment. Yet, as they climb the value chain, these countries also face mounting exposure to geopolitical shocks and technological dependencies.

ASEAN's share of global semiconductor export growth is estimated to have risen from 20 per cent in 2015 to nearly 30 per cent in 2024. The region is literally 'powering up' with analogue semiconductors serving as its strongest growth driver, accounting for roughly half of the global trade expansion over the last decade.

Malaysia and Singapore dominate production, while Vietnam and Indonesia are increasing imports to support new electric vehicle manufacturing bases. Optoelectronic, sensor, and discrete chips, a major class of chips used for sensing light, have grown from 18 to 24 per cent of world exports, driven by Vietnam and Thailand's new assembly and testing capacity.

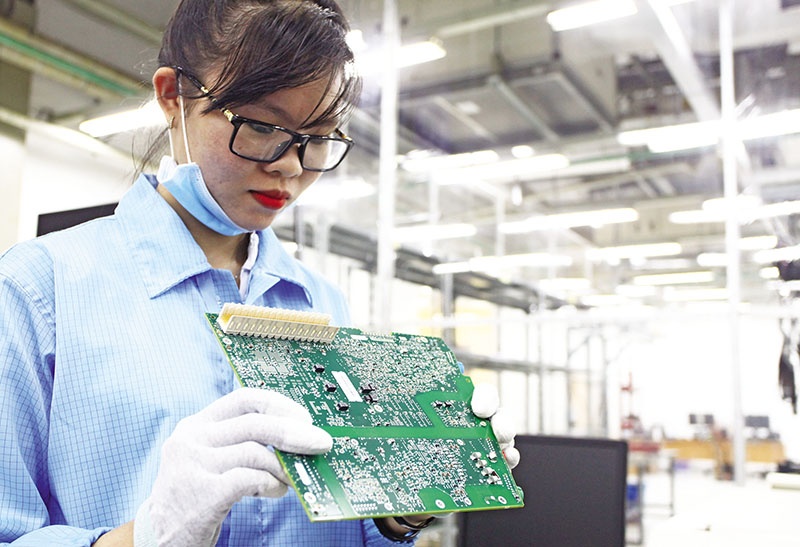

This pattern reveals a multi-tiered ecosystem – Singapore and Malaysia underpin high-value production and testing, while Vietnam and Thailand are advancing through new assembly, packaging, and printed circuit board (PCB) facilities. Integrated circuit (IC) design parks are also emerging across all four destinations.

The report pointed out that governments across the region are pursuing distinct yet complementary industrial-policy models.

Singapore has adopted an innovation-driven path, embedding its semiconductor plans within the Research, Innovation and Enterprise 2025 and Manufacturing 2030 strategies. With more than $23 billion in new projects – such as the Vanguard-NXP power-chip fab and Micron's high-bandwidth-memory plant – the city-state remains ASEAN's research and development (R&D) and design leader.

In 2024, Malaysia unveiled its National Semiconductor Strategy, supported by USD5.9 billion in fiscal incentives, aiming to shift from outsourced assembly and testing to advanced packaging and IC design. Key initiatives include Infineon’s USD7 billion silicon carbide fabrication facility (fab) in Kulim, new IC design parks in Puchong and Cyberjaya, and Sarawak’s semiconductor fabs, signalling a strategic pivot towards power and design specialisation.

Vietnam represents a fast-follower model, using foreign partnerships to accelerate industrialisation. The 2024 national semiconductor strategy targets 100 design firms and one fab by 2030, expanding to 300 firms and three fabs by 2050. Amkor's $3.6 billion packaging plant and Samsung's multi-billion-dollar expansions anchor this growth.

Thailand, a manufacturing integrator, is building an ecosystem around PCBs and power devices under its National Semiconductor and Advanced Electronics Strategy. New research and development (R&D) centres, such as the KMITL Academy of Innovative Semiconductors, and investments by Toshiba and Murata aim to link the electronics and electric vehicle supply chains.

Geopolitics now defines much of this growth. The four governments are navigating an increasingly crowded field of strategic partnerships. In the past, Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships (CSPs) between ASEAN states and major powers were broad diplomatic instruments. Today, they have become increasingly semiconductor-oriented, signalling a deeper alignment between foreign policy and technology strategy.

But diversification remains the operative word. While the US remains a major investor in Vietnam and Malaysia, Taiwanese and European firms dominate Singapore's inflows, and Chinese and Taiwanese manufacturers lead Thailand's PCB investments. New players – India, South Korea, and Japan – are brokering semiconductor CSPs and MoUs focused on talent and R&D cooperation.

At the same time, intra-ASEAN coordination is slowly emerging. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand are exploring a regional growth triangle in semiconductor trade, and the proposed ASEAN Framework for Integrated Semiconductor Supply Chain aims to align standards and incentives.

Despite its diversification, the region's position is not entirely worry-free. The boom in data-centre construction – driven by AI and localisation rules – has created new vulnerabilities. Singapore and Malaysia, the region's data-centre hubs, have been drawn into US investigations over possible re-exports of restricted Nvidia chips to Chinese entities. Malaysia's new export-permit regime for high-performance AI chips underscores the balancing act between US compliance and Chinese investment.

Fiscal strain poses another risk. Generous incentives and tax breaks have triggered 'incentive shopping', where firms push governments towards a race to the bottom. Without coordination, such subsidy races could undermine long-term fiscal stability and environmental goals.

Trade concentration adds another layer of exposure. Singapore imports 72 per cent of analogue chips from South Korea and half of its memory chips from Taiwan, while Malaysia sources 86 per cent of its analogue chips from Singapore.

Vietnam and Thailand depend significantly on US demand for optoelectronic, sensor, and discrete exports. Although new partners such as India and Europe are gaining a foothold, true diversification remains limited.

While the four countries have made impressive strides, their collective success should be viewed cautiously. Gaps in innovation capacity and governance still separate Singapore from its regional peers. Singapore has invested heavily in public R&D, capital markets, and education, whereas Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand continue to rely on foreign capital and technology spillovers. Without stronger regional research systems and innovation ecosystems, Southeast Asia risks remaining a manufacturing arm of global firms rather than a source of new technologies.

ASEAN’s semiconductor future rests on a delicate balance: seizing opportunities from US–China competition while avoiding dependency risks. CSPs focused on semiconductor cooperation may offer diplomatic safeguards, but they also raise expectations for performance and alignment. Sustaining momentum will depend on whether these four countries can move beyond investment attraction to innovation creation – shifting from production hubs to active participants in shaping the next generation of chips.

| Vietnam’s semiconductor leap: turning vision into global leadership The Vietnam Semiconductor Industry Exhibition 2025 (SemiExpo Vietnam 2025) opened on November 7, marking an important milestone in Vietnam’s journey towards high-tech integration and global innovation. |

| Vietnam bets on AI and semiconductors to drive tech transformation A SEMIExpo Vietnam 2025 conference spotlighted AI and semiconductors as the dual engines powering the country’s technological leap. |

| Manufacturing deals bring stronger supply chains closer Supply chain diversification is fuelling mergers and acquisitions in the manufacturing and industrial sector as companies look to acquire Vietnamese-based assets. |

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- France supports Vietnam’s growing role in international arena: French Ambassador (January 25, 2026 | 10:11)

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

- Russian President congratulates Vietnamese Party leader during phone talks (January 25, 2026 | 09:58)

- Worldwide congratulations underscore confidence in Vietnam’s 14th Party Congress (January 23, 2026 | 09:02)

- Political parties, organisations, int’l friends send congratulations to 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:33)

- 14th National Party Congress: Japanese media highlight Vietnam’s growth targets (January 21, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th National Party Congress: Driving force for Vietnam to continue renewal, innovation, breakthroughs (January 21, 2026 | 09:42)

- Vietnam remains spiritual support for progressive forces: Colombian party leader (January 21, 2026 | 08:00)

- Int'l media provides large coverage of 14th National Party Congress's first working day (January 20, 2026 | 09:09)

- Vietnamese firms win top honours at ASEAN Digital Awards (January 16, 2026 | 16:45)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version