Investment options for infrastructure projects

|

| Bill Magennis, head of Vietnam at international law firm Allens and Huyen Nguyen, senior associate |

Much has been written about the vast needs of Vietnam for infrastructure. That is undisputed and governmental communications have consistently welcomed foreign investment in infrastructure.

Since the turn of the century, foreign investments have contributed to built and operate important infrastructure. This includes four power stations (each in excess of 1,000 megawatts), two offshore gas projects and related pipelines, one refinery, more than 40 ports, a number of renewable power projects, a waste disposal plant, and some industrial and urban zones.

Approximately 15 power plants and a number of other infrastructure projects are the subject of signed contracts and have been licensed, and are at various stages of construction or financing. Other projects are under negotiation including two mega gas-to-power projects. One is Blue Whale offshore Danang with investment by ExxonMobil, which will supply gas for 2,225MW of power at the Dung Quat power complex.

The second is Block B South West Vietnam, with the majority being owned by state-owned Vietnam Oil and Gas Group; and investment by Mitsui Oil of Japan and PTTEP of Thailand. This will supply gas for 2,910MW of power. Some projects, including water supply and ports, were documented and licensed but not built for various reasons, including inability to secure financing.

So, the question now is whether or not Vietnam’s infrastructure investment framework is attractive enough for foreign investors. The short answer, currently, is yes. The framework is attractive enough but some additions would add to this.

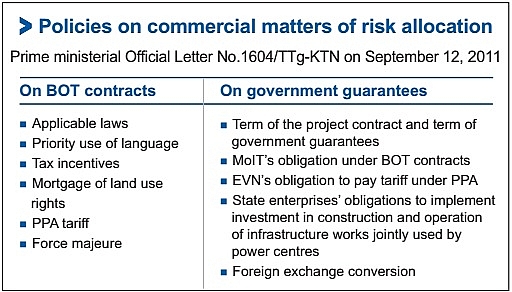

Ideally, important and time saving policies suitable to attract foreign investment announced by the prime minister in documents such as Letter 1604 could be concretised in higher level legislation for universal application.

There are three legal pathways for foreign investment in infrastructure. The first is to follow the general investment law in the same manner as all other types of investment in the country. The second is to follow the general investment law supplemented by project-specific contracts with the government (or a ministry or a people’s committee). The Nam Con Son gas project and Nghi Son refinery project are two of this kind. The third pathway is to follow the special public-private partnership (PPP) legal framework. Phu My 3, Phu My 2.2, Mong Duong 2, and Vinh Tan 1 power plants are some examples of this.

|

Improvements seen

The general investment law has so far been used for completed industrial and urban zone infrastructure, renewable power, and port projects. It has proven satisfactory for domestic and foreign investment generally but in the case of renewable power, the industry specific law has deterred some investors and financiers.

Power purchase agreements (PPA) are required to follow a standard form which contains contents generally regarded as unbankable by foreign investors as well as their lenders.

Provisions relating to breach of contract and dispute resolution have also been

problematic. However, this has not deterred local and foreign investors, with the result that there are approximately 130 licensed renewable projects of which at least 19 involve international investors.

It is encouraging to note that the latest published PPA form for wind power has improved terms on breach of contract. Hopefully this improvement will be extended to all new renewable projects.

The general investment law supplemented by contracts with the government was successfully used for the offshore gas projects and the refinery already mentioned. The contract with the government was called the Government Guarantees and Undertaking (GGU) and provided for allocation to the government of certain project risks that it was in the best position to control.

It also included certain agreements in relation to contractual performance of state-owned enterprises which provide materials or buy project products, currency, government-provided works, and some legal issues such as change-in-law, mortgages, and compensation in certain cases. Coal and gas electricity generation investment, meanwhile, has been under what is now known as the PPP regime.

The PPP regime started life as a build-operate-transfer (BOT) system and related concepts regime when the then Law on Foreign Investment was amended in 1992 to

introduce the BOT concept under which investors could contract with the government via a state-authorised body to build a particular project, operate it for a period of time, and then transfer it to the government.

The BOT contracts were signed together with a supporting GGU. The first BOT decree detailing the regime was issued in 1993 and amended regularly until replaced by a PPP decree in 2015. Most if not all licensed PPP projects with foreign investment began under the BOT regime. Some have been licensed under the PPP regime but so far as we know no major project with foreign investment that was first conceived under that regime has been licensed.

The possible situation of no licensed PPP projects with foreign investment created under the regime after more than four years of operation raises questions.

The answer to why this may have occurred lies not in any issue arising in the legal framework, but simply from the inability of foreign and governmental negotiating parties to come to agreement on the detail of essentially commercial matters including risk allocation.

This may be partly explained by Vietnam wishing to move on from protections granted up to 20 years ago when the country was an untested investment destination and investors or lenders did not agree to all the changes to precedent sought by Vietnam.

Sector hurdles

There are both good prospects and challenging hurdles for Vietnam when it calls investment from foreigners into infrastructure development.

In the power sector, there are unallocated projects in the national Power Development Master Plan VII and reports of looming power shortages. This represents an opportunity for repeating prior successful investment in large power plants.

In terms of transport, so far potential road investments have faced difficulties in agreeing applicable financial parameters. This may change. Over 50 overseas investor groups have reportedly submitted bidding documents to join the Ministry of Transport’s bids to develop eight PPP component projects along the Eastern North-South Expressway. Since at least 2014, railway and airport projects have also been earmarked for outside investment. As is the case for roads, new financial mechanisms will be required. In the liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, the gas master plan provides for a national network of LNG terminals, storage, and pipelines. This is new for Vietnam. Several foreign investor groups are proposing LNG investment, which will likely be outside the PPP regime.

Furthermore, there are a current potential and general challenge towards attaining successful foreign investment in infrastructure. That is the upgrading of the status of the current government decree on PPP to a law. The first draft PPP law was published in May.

The good news is that key elements of the prior successful regime of incentives and protections for foreign investment in BOT/PPP projects are essentially preserved. Besides, the draft also introduces some ideas that foreign investors consider unattractive. These include, amongst other things:

-Compulsory requirements on the use of domestic contractor/sub-contractor and domestic suppliers;

-Requiring a performance security deposit by the investor;

-Requiring financing to be completed within 12 months;

-Application of regulations on management and use of public investment;

-Compensation for expropriation and requisition in accordance with Vietnamese law; and

-Vietnamese governing law for the project contracts.

It would make PPP projects’ investment more enticing for foreign investors and lenders if these items did not move into the next draft. It would also be helpful if some provisions could be added, expressly enabling risk allocation along lines previously agreed but which so far have had to be renegotiated for each project. These might include provisions on the mortgage of land use rights, and compensation details supplementing existing law in case of a change in law or necessary expropriation.

Vietnam has changed remarkably since the first generation GGU in 2002 and is no longer an unknown investment destination. It has a track record of making reasonable contracts and honouring them in every detail. This should give confidence to investors and lenders not to seek all that was agreed in the past. Perhaps foreign investors/lenders in new projects can consider having more pragmatic and flexible positions on some risks.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Hermes joins Long Thanh cargo terminal development (February 04, 2026 | 15:59)

- SCG enhances production and distribution in Vietnam (February 04, 2026 | 08:00)

- UNIVACCO strengthens Asia expansion with Vietnam facility (February 03, 2026 | 08:00)

- Cai Mep Ha Port project wins approval with $1.95bn investment (February 02, 2026 | 16:17)

- Repositioning Vietnam in Asia’s manufacturing race (February 02, 2026 | 16:00)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

- Navigating venture capital trends across the continent (February 02, 2026 | 14:00)

- Motivations to achieve high growth (February 02, 2026 | 11:00)

- Capacity and regulations among British areas of expertise in IFCs (February 02, 2026 | 09:09)

- Transition underway in German investment across Vietnam (February 02, 2026 | 08:00)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version