TPP controversy over ISDS

|

During the long negotiation for the TPP agreement, one of the most controversial issues analysed by economists and politicians was Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) terms in Section B of Chapter 9 - Investment. ISDS is a legal system under which foreign investors can legally challenge the host country’s regulations, outside of the countries territories. This system is unusual in international law. While most international courts only allow disputes between states, ISDS, however, creates one-way rights: investors can sue governments, but not vice versa.

ISDS procedures

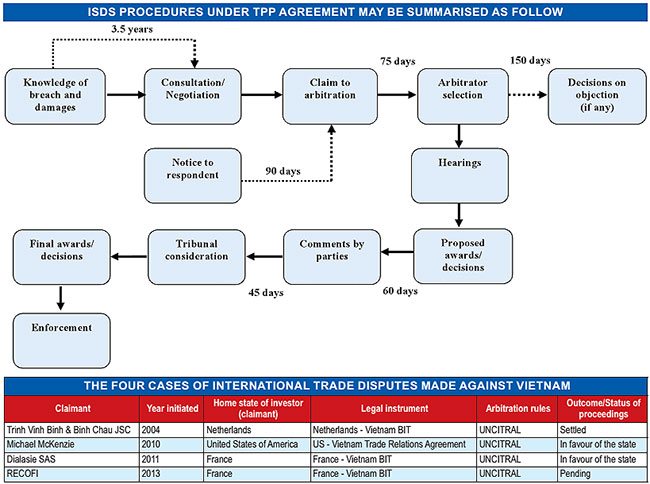

ISDS procedures under the TPP agreement may be summarised as follow (see chart). Is this a good or bad thing?

With the provision allowing an investor to claim against breaches of obligations (e.g., obligations to offer national treatment or most-favoured-nation treatment to the other Party’s investors), or an investment authorisation or an investment agreement, ISDS terms in the TPP agreement give foreign investors a wide range of rights. This is the case even when they have never executed an investment project in the host countries (i.e., such investors attempt to make investment such as channeling resources or capital in order to set up a business or applying for a permit or license). ISDS terms under the TPP agreement give encouragement for consultation and negotiation, using non-biding third-party procedures such as good offices, conciliation or mediation between the claimant and the respondent. Subsequent procedures shall be based on a mutual agreement between the disputing parties, including choice of arbitrators, arbitration place, language used or whether or not hearing(s) should occur.

The legal challenges and disputes are decided by arbitrators hired for that case only. The typical set-up is that the foreign investor appoints an arbitrator, the host country appoints a second, and the two parties appoint a third to chair the case. After their decision, the arbitrators are paid by the parties and the tribunal is dissolved.

More rights and more flexibility of ISDS terms in the TPP agreement may be welcomed by investors, however, will it be welcomed by the host country?

ISDS terms in the TPP agreement state that each party must provide for the enforcement in its territory of an arbitration award which has been rendered in accordance with the TPP agreement. As such, foreign arbitrators can order governments of host countries to pay compensation against the monetary damages and applicable interests to the investor, who can then enforce arbitrators’ decisions with the full force of the domestic courts.

Some of TPP parties were not very happy with the provision that awards would be final and that there is no court for appeals. Therefore, the TPP agreement set out a “potential” chance for an appellate mechanism to review ISDS awards, rendered by relevant tribunals, provided that such mechanism will provide for transparency of proceedings and such changes must be subject to further development in the future under “other institutional arrangement” by the Parties to the TPP agreement.

ISDS and the application in Vietnam

Litigation is the dispute settlement method most “preferred” in Vietnam. Cases of arbitration and other alternative methods are on the rise but it may take more time for them to become effective. According to statistics from the Vietnam International Arbitration Centre (VIAC), only around 1 per cent of total commercial disputes, equivalent to 879 cases, were settled by arbitration as of June 2015. In international trade, only four disputes have so far been initiated against Vietnam (under ISDS agreement) which are listed in the table above.

During the negotiations of the TPP agreement, the main concern of the government was eligibility of claimants, potential claimed entities and applicable procedures. In particular, concerns about whether or not authorised entities and state-owned-enterprises (SOEs) would be claimed under ISDS as a “state body”. This is due to the fact that SOEs still play a substantial role in the current Vietnamese economy. In addition, the government has questions concerning arbitration proceedings such as prior consent by the state, confidentiality, applicable regulations (the TPP agreement and domestic laws or even international laws), etc.

ISDS is therefore seen as a controversial matter. Even in developed economies such as the US, Canada and Australia, there are concerns and objections to the mechanism. Vietnam is no different. Here, we may suffer losses and damages because ISDS terms do not allow local investors to initiate arbitration proceedings against their own government, leading to an inequality between foreign and local investors. On the other hand, for each disputed case, huge arbitration and compensation costs, when compared to the Vietnamese economic scale, will put pressure on the national budget. It will affect economic development on a macro level. Another essential point is national sovereignty: the local law system of Vietnam is insufficient to deal with global issues and as long as there is no appellate mechanism reached by TPP parties, Vietnam’s government faces the risk of being forced to change its domestic regulations to “survive” before the new claims from multinational companies. Nevertheless, some Vietnamese government officials gave optimistic comments on the TPP agreement, including the ISDS terms. They seem to believe strongly in the improvement of local regulations as well as the active preparation by relevant authorities, learning from practical cases. It may take 18 – 24 months for the TPP agreement to take effect. Hopefully, Vietnam will adapt to this opportunity. Until then, ISDS terms are still a puzzle to both state authorities and local investors.

By Vo Ngoc Dao and Nguyen Thi Thu Hong - Laywers of ATD Lawyers

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- IP alterations shape asset strategies for local investors (January 22, 2026 | 10:00)

- 14th National Party Congress: Vietnam - positive factor for peace, sustainable development (January 22, 2026 | 09:46)

- Japanese legislator confident in CPV's role in advancing Vietnam’s growth (January 22, 2026 | 09:30)

- 14th National Party Congress: France-based scholar singles out institutional reform as key breakthrough (January 21, 2026 | 09:59)

- 14th National Party Congress: Promoting OV's role in driving sustainable development (January 20, 2026 | 09:31)

- 14th National Party Congress affirms Party’s leadership role, Vietnam’s right to self-determined development (January 20, 2026 | 09:27)

- Direction ahead for low-carbon development finance in Vietnam (January 14, 2026 | 09:58)

- Vietnam opens arms wide to talent with high-tech nous (December 23, 2025 | 09:00)

- Why global standards matter in digital world (December 18, 2025 | 15:42)

- Opportunities reshaped by disciplined capital aspects (December 08, 2025 | 10:05)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version