Improving frameworks in order to reach the Industry 4.0 peak

|

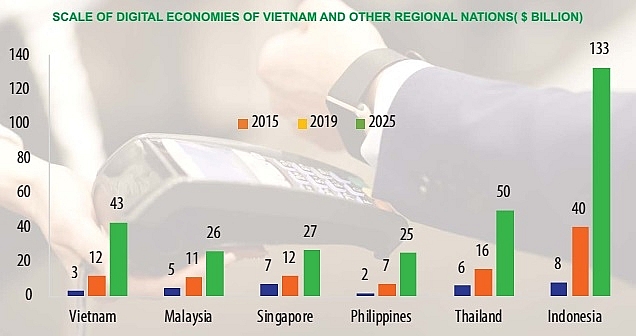

| A unified concept for regulatory sandboxes will help Vietnam expand its digital economy on a regional level |

As the whole Vietnamese economy is seeing great implications from the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the local regulatory system is facing major challenges for revision and perfection to adapt to Industry 4.0 development requirements.

|

| Dr. Tran Thi Quang Hong, head of the Department of Economic-Civil Legislation at the Ministry of Justice’s Institute of Legal Science |

The first challenge involves the capacity to address newly-arising issues rationally.

Amid robust technology development, the knowledge gap between technology developers and policymakers is allegedly widening. Policymakers often find it hard to get a good grip of novel technologies, whereas their responsibility is to craft regulations to put such new tech under control.

Looking at the development of the passenger transport system based on car-hailing platforms such as Uber and Grab, we can see how difficult the work of regulators is to tackle new matters. While these companies have grown into major entities providing widespread services in the marketplace, Vietnam still lacks a compatible law to fix the service, leading to fierce social conflict and legal disputes between stakeholder parties.

The second challenge pertains to the adaption of laws to the fast pace of Industry 4.0. In fact, the legal system often lags behind social evolution, let alone technology development. The example of Uber and Grab attests to this reality.

As technology is developing at a galloping pace, the largest challenge to regulators is to ensure a law with balanced interests, while it could react flexibly to continually arising matters entailed by Industry 4.0.

Concept and role

A regulatory sandbox is a framework set up by agencies to allow small-scale, live testing of innovations by private companies in a controlled environment (operating under a special exemption, allowance, or other limited time-bound exceptions) under state authority supervision. When tested, mistakes and errors may appear that can be fixed at once to ensure the applications are of good quality for practical use.

Application is therefore increasing worldwide as many governments find a suitable management method to deal with new matters from technologies that are uncovered by existing legislation that cannot be changed overnight.

This mechanism allows the deployment of new ideas, through which providing opportunities for technology developers to prove social and economic benefits their ideas and technologies could bring.

Regulatory sandboxes also allow regulatory agencies to assess new technology aspects that are still uncovered by law, and on that basis introducing suitable guiding rules. They might forbid further deployment, allow further experimentation in a controlled manner, or allow wide application.

With these eminent features, this management method is supposed to perfectly match robust technology development pace in the digital age.

The first sandbox was launched in the United Kingdom in 2015, and many countries have followed suit. Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia have formulated and implemented the sandbox in Southeast Asia thus far.

Regulatory sandboxes have been hot on the agenda at diverse policy dialogues on technology development in Vietnam in recent years. Many innovative startups and experts often make proposals recommending their use in business practice. Meanwhile, policymakers have also advocated the building of such sandboxes. Notwithstanding, such a product for testing new technology application is seemingly still absent in Vietnam.

In the status as a legal environment for testing new technology in Vietnam, regulatory sandboxes are attached to allowance and supervision of the management authority of a particular field and sector. These agencies by essence are administrative units whose functions are supervising legal implementation based on concrete principles.

Meanwhile, they only apply to matters derived from the use of fresh technologies that are still uncovered by existing legislation. Their application, therefore, requires state management authorities to go beyond common legal execution functions and hold certain initiative in implementing concrete management measures.

Efforts must also gear towards ensuring impartiality, efficiency, and seamless implementation of the testing process, avoiding abuse of power, and losing the opportunity of new technology application due to late enactment of relevant laws. These matters must soon be resolved to accelerate the formation of regulatory sandboxes in Vietnam.

In August the prime minister approved a project on promoting the model of the sharing economy in Vietnam which confirms the stance of “implementing new policy experimentation in deployment and application of new technologies in the sharing economy”.

The project entails fresh opportunities for regulatory sandbox models to go ahead in Vietnam, and in diverse fields of the local economy.

Until now, apart from being mentioned in the premier’s decision, no rule exists that provides a unified concept about regulatory sandboxes as well as how to implement them in practice. Meanwhile, deployment would involve multiple matters such as choosing businesses allowed to take trials; the type of technology allowed to go on trial; timeframe and space for experimentation; the supervisor’s responsibility during the trial process; and assessment requirements during the process, among other areas.

The factors for success

As law execution bodies, without requirements on responsibilities and certain exclusion principles, state management agencies might have no motivation in pushing up deployment of a regulatory sandbox in the fields under their management. In addition, as their deployment relates to selection, it is important to ensure transparency in selection criteria, allowing equal access to all stakeholder parties.

For those reasons, having in place a legal corridor for deployment in the current context proves very necessary, and that legal corridor must ensure satisfying the several requirements.

First, it must provide a unified concept about regulatory sandboxes, associated goals, and development approach. Second, it must allow state management agencies in particular fields and sectors to exercise certain rights in deployment of a sandbox in their fields. For instance, these bodies will be allowed to set selection criteria in choosing businesses or individuals to take on trial.

Third, the legal corridor should clearly define responsibilities of state management agencies in experimentation supervision and support in deployment process. Fourth, it has to set common rules for deployment, including the rules on space and time limits, and conditions for time and space extension if necessary.

Next, regulations have to clearly define the responsibilities of individuals and organisations partaking in the experimentation process. These entities might be exempted from several legal obligations such as having an operating license, but still obliged to handle civil and legal responsibilities.

Finally, a legal framework must be created to assess experimentation to ensure each trial project in a regulatory sandbox is fully assessed, leveraging diverse metrics such as social and economic benefits from new technology application, and the possibilities of risks towards consumers.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Tag:

Tag:

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- State corporations poised to drive 2026 growth (February 03, 2026 | 13:58)

- Why high-tech talent will define Vietnam’s growth (February 02, 2026 | 10:47)

- FMCG resilience amid varying storms (February 02, 2026 | 10:00)

- Customs reforms strengthen business confidence, support trade growth (February 01, 2026 | 08:20)

- Vietnam and US to launch sixth trade negotiation round (January 30, 2026 | 15:19)

- Digital publishing emerges as key growth driver in Vietnam (January 30, 2026 | 10:59)

- EVN signs key contract for Tri An hydropower expansion (January 30, 2026 | 10:57)

- Vietnam to lead trade growth in ASEAN (January 29, 2026 | 15:08)

- Carlsberg Vietnam delivers Lunar New Year support in central region (January 28, 2026 | 17:19)

- TikTok penalised $35,000 in Vietnam for consumer protection violations (January 28, 2026 | 17:15)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version