Clearing up the future of the planet

|

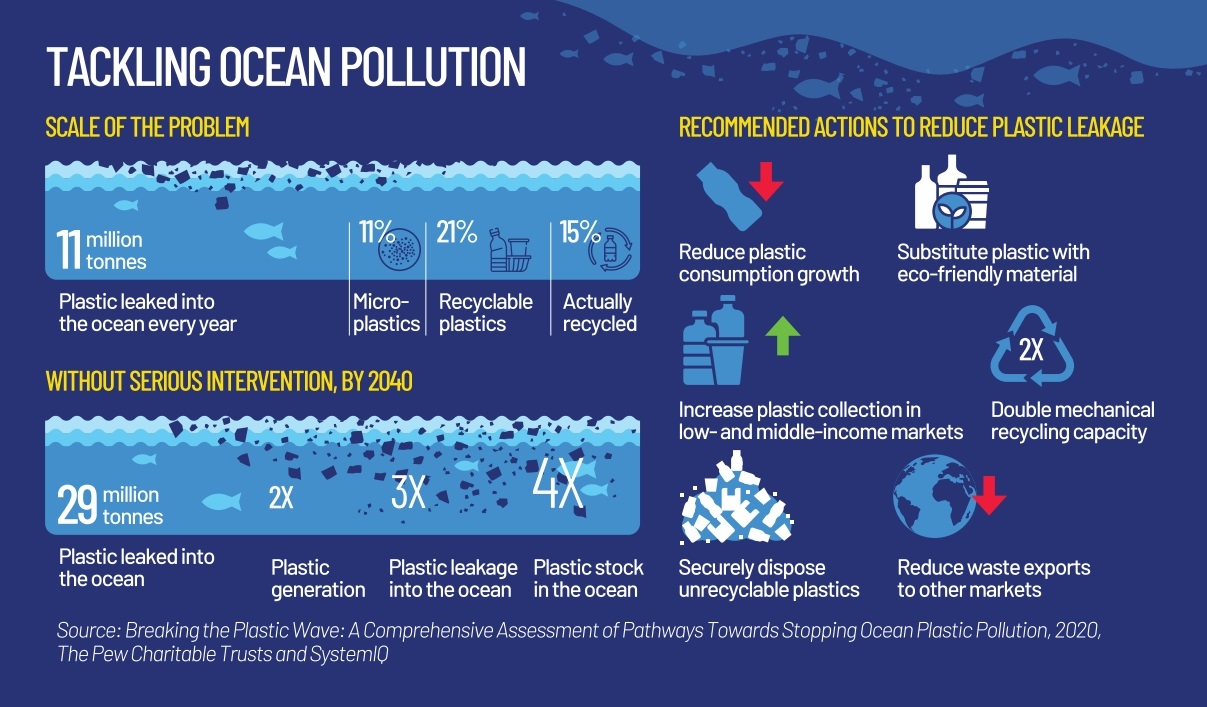

Plastic is used all over the world for thousands of applications in many economic sectors. Its low cost, light weight, durability, and flexibility to be shaped and coloured in any form have pushed the material onto the shelves of supermarkets, into children’s toy collections, and their parents’ houses and vehicles. However, its popularity and ubiquitous application have also caused major pollution and waste challenges, with an estimated 11 million tonnes of plastic leaking into the ocean every year – a figure that is expected to nearly triple to 29 million tonnes in 2040 without intervention.

Compared to other materials, plastic is a relatively new substance, only invented in the 19th century. While in 1950, global plastic production was estimated at two million tonnes, its scale soared to 348 million tonnes in 2017, becoming a global industry valued at $522.6 billion, according to the white paper Breaking the Plastic Wave: A Comprehensive Assessment of Pathways Towards Stopping Ocean Plastic Pollution, updated last October by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“Asia accounted for about 51 per cent of global plastics production in 2018, with China alone producing around 30 per cent of the world’s plastics,” stated the 2019 report by PlasticsEurope Market Research Group. Within the continent, East and Southeast Asia form hotspots for plastic waste leakage into the ocean.

Nevertheless, littering is a growing global threat to marine ecosystems and related economic sectors of nearly all nations. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, up to 90 per cent of marine litter consists of plastics, of which much comes from single-use plastic products and packaging, in addition to abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear – both of which affects over 800 species in marine and coastal environments.

Every day, humans continue to add to the pollution of the global ocean that covers 71 per cent of the Earth. The consequences of human-induced factors are manifold, including phenomena like lowered or depleted oxygen, oil and chemical spills, marine debris, and plastics and microplastics, to name just a few.

“80 per cent of pollution to the marine environment comes from the land,” states the US National Ocean Service. In addition to obvious polluting factors, nonpoint source pollution – such as small drops of oil from motor vehicle engines that eventually make their way to the sea – count as one of the biggest sources of ocean pollution.

While correcting the harmful effects of nonpoint source pollution is costly and complicated, much of the litter and debris that swims around the ocean is simply caused “by our own unsustainable consumption and production,” said Inger Anderson as quoted by the Oxford University Economic Recovery Project on April 30. Anderson is the executive director of the UN Environment Programme and member of the panel supporting the white paper Breaking the Plastic Wave.

In a video on marine plastic pollution in Osaka city, Anderson said, “Plastic pollution is one of the most visible signs of our unsustainable production and consumption. It is a global crisis that is threatening the environment, human health, and our economies across the world. This global crisis requires an urgent global response.”

The same video – in which representatives from nations like Ukraine, India, Vietnam, Kenya, and Mexico portray the reality of the crisis as well as ideas for solutions – also repeats an uncomfortable estimate that has circulated among academia and media for the last five years.

By the year 2050, there may be more plastics than fish (by weight) in the ocean – a statement that goes back to a 2016 report by the Ellen McArthur Foundation.

The turning point

As one of several action plans around the world, the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision is the G20’s implementation framework for actions on marine plastic litter, in which members agreed to effectively tackle marine litter by encouraging voluntary actions by all members. The G20 wants to foster a “comprehensive life-cycle approach to urgently and effectively prevent and reduce plastic litter discharge to the oceans, in particular from land-based sources,” as explained on the framework’s website created by the Ministry of Environment in Japan and managed by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies.

Measures include eco-friendly waste management solutions, clean-up of marine plastic litter, and the prevention and reduction of plastic waste generation and littering, as well as the promotion of sustainable consumption and production, with the final goal to reduce additional pollution by marine plastic litter to zero by 2050.

Similarly, the white paper Breaking the Plastic Wave presents an evidence-based roadmap that describes how to radically reduce ocean plastic pollution by 2040 and that shows there is a comprehensive, integrated, and economically attractive pathway. The publication was co-developed with 17 experts with broad geographical representation, and its technical underpinnings were published in the article Evaluating Scenarios Toward Zero Plastic Pollution in peer-reviewed journal Science. According to the white paper, “a future with approximately 80 per cent (82 ±13 per cent) less annual plastic leakage into the ocean relative to business as usual is achievable by 2040 using existing technologies.”

But there is no single solution to the crisis. The paper showcases the analysis of eight system interventions, which could be applied within six ranked scenarios, each comprising a different combination – or lack – of system interventions.

Starting at “business as usual”, the model shows that the global mass of mismanaged plastic could grow from 91 million tonnes in 2016 to 239 million tonnes in 2040, with plastic leakage to the ocean growing from 11 million tonnes in 2016 to about 29 million tonnes in 2040.

The best-case scenario, the system change model, would include all eight system interventions – such as reduced consumption, plastic alternatives, recycling, and chemical conversion – but goes much further than the current commitment level of all nations.

In addition to reducing global plastic leakage from 11 to five tonnes by 2040, as well as related greenhouse-gas emissions by around 23.8 per cent, the system change model would also be the most affordable for governments, with estimated costs decreasing from the current $670 billion to $600 billion.

Circular solutions

While the white paper and the commitments of the G20 discuss the necessary global approach, regional solutions in East and Southeast Asia include numerous initiatives at ASEAN, national, provincial, and local level.

In China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, the Rethinking Plastics – Circular Economy Solutions to Marine Litter Project supports activities for the transition to a circular economy with a focus on waste prevention and management.

Regional teams of experts like the one based in Vietnam implement activities, share experiences from other countries, and learn from pilot projects in different areas of action. These pilot projects include the replacement of single-use plastic items, deposit-based recollections programmes, and extended producer responsibility approaches, which include the waste stage of a product in the product’s life cycle and the manufacturer’s duty.

At workshops with local stakeholders and government representatives, the Rethinking Plastics team is discussing and developing hands-on solutions that could begin at a product’s design stage, such as scrutinising the necessity of packaging altogether and a possible selection of renewable and bio-degradable materials that could be used.

“The fight against plastic pollution is a global objective with specific challenges and solutions, where each ministry, city, province, and individual in society has a role to play. While global and national action plans have provided an initial framework, the operational implementation raises many difficulties, particularly in terms of governance,” said Fanny Quertamp, senior adviser for Vietnam at Expertise France. “The dialogue with our partners at ministerial level is essential, allowing us to identify needs and to work together on responses. Leveraging EU and Southeast Asian experience, Vietnam is crafting its own model which is creative, ambitious, and practical.”

Quertamp added, “Every day, I see the commitment of ministries and business associations. Taking inspiration from foreign models is one thing, identifying what is relevant and developing the current institutional and regulatory framework is another. The public authorities cannot meet these challenges alone and exchange with other stakeholders is very valuable.”

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Keppel Land raise plastic waste awareness (July 09, 2022 | 13:45)

- 3Vs for gender-inclusive circular era (July 01, 2022 | 14:33)

- Alliances formed in mission to alter behaviours (July 01, 2022 | 14:19)

- Plastic use drop hinges on consumers (July 01, 2022 | 14:03)

- Mainstreaming circular plastic plans (July 01, 2022 | 13:18)

- Applying popular new methods to combat single-use plastic habit (July 01, 2022 | 10:00)

- Retailers endeavor to promote sustainable consumption patterns (June 24, 2022 | 14:46)

- BAEMIN extends green journey in Vietnam (June 23, 2022 | 14:51)

- Closing event of Rethinking Plastics heralds new age of combatting plastic pollution (June 23, 2022 | 11:53)

- Talkshow Innovative Solutions & Substitutes for Single-use Plastic towards Green Consumption (June 22, 2022 | 20:46)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version