Modern technology complementing flood-resilient home creations

|

| Thousands of storm- and flood-resilient homes have been built in Vietnam since 2017 |

As fate would have it, Tan An hamlet is annually sabotaged by strong storms and floods, with many families becoming homeless as their shabby houses succumb to the rage of nature.

The recent storms and subsequent flooding in the hamlet, which belongs to Loc Binh commune in coastal Phu Loc district of the central province of Thua Thien-Hue, forced numerous locals to higher ground to find shelters. However, a number of poor farmers, like Phan Thi Hanh and her daughter, stayed safe in their newly-built house, provided for them in April and located right next to their run-down old home.

Hanh is among 26 poor households in the village given new homes, which are part of a nearly $42 million project to improve the resilience of coastal communities to climate change in Vietnam. Funded jointly by the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Vietnamese government, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the capital includes $29.5 million in grants from the GCF and $1.6 million from the UNDP, while the remaining comes from the government.

The project is being implemented by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Construction (MoC), and the UNDP from 2017 to 2021.

“The house is good. The mezzanine especially helps us to stay safe when there’s flooding,” Hanh said. “We used to be very anxious and miserable whenever the floods came.”

Phan Ba Chiem, Deputy Chairman of Loc Binh commune, said that after the storms all 26 of the project’s houses in the village still stand solidly, without any damage.

Those in Loc Binh are not the only ones to be offered such houses – many others in the south-central province of Quang Ngai are also afforded the same luxury.

Nguyen Thi Mun, 78 years old, lives in Binh Chanh commune of Binh Son district in Quang Ngai. Over the past years, life has been particularly tough, and her 83-year-old husband Vo Khanh has a long-term illness. The couple makes very little income, and every time there was a storm, parts of their old house were damaged.

Unfortunately, due to its coastal location, Binh Chanh is prone to storms and flooding. Every time the water rises, families are displaced. “Whenever there was flooding, the commune authorities came to pick me up by boat, took me to a higher area, and gave me instant noodles for food,” Mun said. She had to stay there until the water – which usually reaches 1.5 metres high – withdrew a few days later.

Eventually, Mun was provided with a new house under the project. “Now I can go up to the mezzanine and stay there during storms and floods, keeping my valuables and food safe. I can go up by myself, because the stairs have a railing I can hold onto. I can bring everything I need up there, including water, clothing, rice and other food, and a small gas stove so that I can stay there comfortably.”

A helping hand

|

| KoBo’s free-of-charge software is helping to supervise construction of new homes |

Under the project, about 4,000 storm- and flood-resilient houses are to be built by the end of next year in five coastal provinces of Thanh Hoa, Quang Binh, Thua Thien-Hue, Quang Ngai, and Quang Nam.

These houses are designed and constructed through a local consultation process with the participation of communities, appraised in terms of technical specifications by the Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology under the MoC, and approved by the provincial departments of construction.

“Since 2017, more than 3,200 houses of this type have been constructed, and all of them have remained safe in defiance of natural disasters,” said Vu Thai Truong, a project management specialist from the UNDP. “Even the Matmo storm in 2019 and the recent Molave storm have failed to shake any of these buildings.”

Nearly 600 storm- and flood-resilient houses have been built in Thua Thien-Hue alone, with high anti-flood floors that have protected locals from any loss of lives or assets, Truong said. “Therefore, they have become shelters not only for the homeowners, but also for other locals living nearby.”

Not all people can be offered such houses, and there must be a selection process. At the top of the list are extremely poor people or single-mother households, who can register at the local commune headquarters if they want to apply for the scheme. Then, they are selected by an authorised team whose members are representatives from different administrative agencies and organisations at all levels in the province. Selected households can choose an appropriate design and local workers themselves, with the money supported by the project via banks.

The homes are based on simple designs to create a stronger structure. Features include a mezzanine level for flood protection, which must be higher than the maximum flood level in the areas in which they are constructed and have an area of at least 10 square metres. All project houses have solid, reinforced structures made with high-quality materials, starting with strong foundations.

Currently, the UNDP is cooperating with the MoC in studying a plan to build such houses for poor people in all 28 coastal provinces of Vietnam.

Useful innovation to monitor construction

The resilient houses are very special for poor people. However, it is little-known that one of the reasons behind the stability of the dwellings lies in the construction process, which is managed and supervised by a tool called KoBo.

“One of the innovations in our resilient housing programme is the ability to include communities’ contributions with real-time monitoring. KoBo is helping us to monitor the construction process by enabling communities to collect and share information and images in the field,” said Caitlin Wiesen, UNDP resident representative in Vietnam.

“The data is collected through mobile phones and then made available in real time in Hanoi for further analysis and reporting, and response to issues raised. It saves time and resources in collecting and analysing data, and enabling rapid responses as necessary,” Wiesen said.

According to Cao Xuan Hien, resilient housing consultant from the UNDP in Vietnam, all three phases for construction of the resilient houses are supervised by KoBo.

Specifically, in the first phase, the operators of this tool – who are often local authorities and project coordinators – feed all information about the old houses into the system: their degradation, damage, and detailed information about the beneficiaries’ families, jobs, and incomes, as well as their residential places and information about the design sample for the new houses.

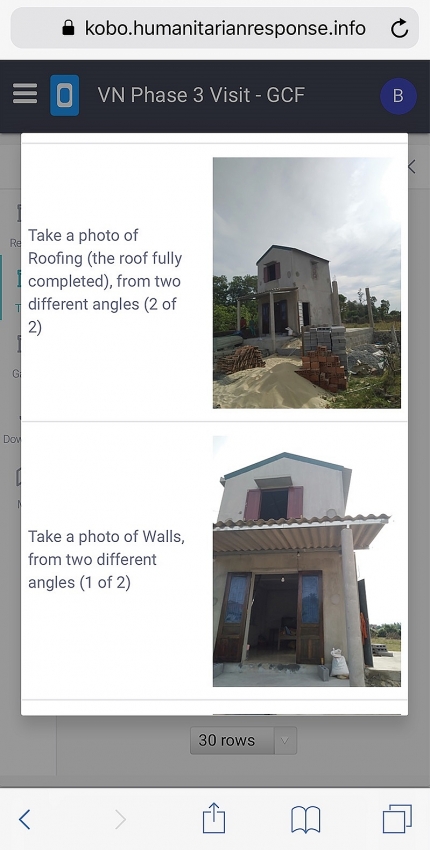

In the second phase, construction images of the houses’ foundations, walls, roof, structure, and building materials are uploaded to KoBo. This helps the project’s management units to supervise the quality and process of construction, especially the techniques being used.

In the third phase, when construction is completed, detailed images of the new houses, donor information, and the beneficiaries’ perceptions about the houses are updated in the platform. Quick feedback is given on any recommendations about the houses, with all requirements in structure and quality strictly obeyed.

“This mobile data collection has provided information and images for supervising house construction, especially in the difficult conditions in terms of geographical distance and given the large number of houses being built at the same time,” Hien told VIR. “In addition, it is also very helpful in that it stores concentrated information for all the houses of all five localities in the same system. When we need any piece of relevant information or a specific image, we have easy access to it.”

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Bac Ai Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant to enter peak construction phase (January 27, 2026 | 08:00)

- ASEAN could scale up sustainable aviation fuel by 2050 (January 24, 2026 | 10:19)

- 64,000 hectares of sea allocated for offshore wind surveys (January 22, 2026 | 20:23)

- EVN secures financing for Quang Trach II LNG power plant (January 17, 2026 | 15:55)

- PC1 teams up with DENZAI on regional wind projects (January 16, 2026 | 21:18)

- Innovation and ESG practices drive green transition in the digital era (January 16, 2026 | 16:51)

- Bac Ai hydropower works stay on track despite holiday period (January 16, 2026 | 16:19)

- Fugro extends MoU with PTSC G&S to support offshore wind growth (January 14, 2026 | 15:59)

- Pacifico Energy starts commercial operations at Sunpro Wind Farm in Mekong Delta (January 12, 2026 | 14:01)

- Honda launches electric two-wheeler, expands charging infrastructure (January 12, 2026 | 14:00)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version