Making sense of requirements in data localisation

|

| Tran Manh Hung & Nguyen Tuan Nghia , BMVN International Law Firm |

Data localisation should be distinguished from data sovereignty, the idea that data are subject to the laws of the jurisdiction in which they are collected. Indeed, each jurisdiction may have different rules relating to the same matter, and as such, each is said to claim “sovereignty” over such data. Data localisation takes a step further by requiring that the initial collection, processing, and storage of a citizen’s data occur first within national boundaries.

Data localisation requirements in Vietnam are found in three legislations. Firstly, the Law on Cybersecurity 2018, Article 26.3 on ensuring information safety provides that “[Enterprises] providing services on telecommunication networks or the internet and value-added services in cyberspace in Vietnam must store such data [here] for a period specified by the government. Foreign enterprises under this scope must also establish a branch or a representative office in Vietnam.”

The scope of the above provision is broad and includes every provider of any service over cyberspace who processes personal data. There are no exceptions to this rule.

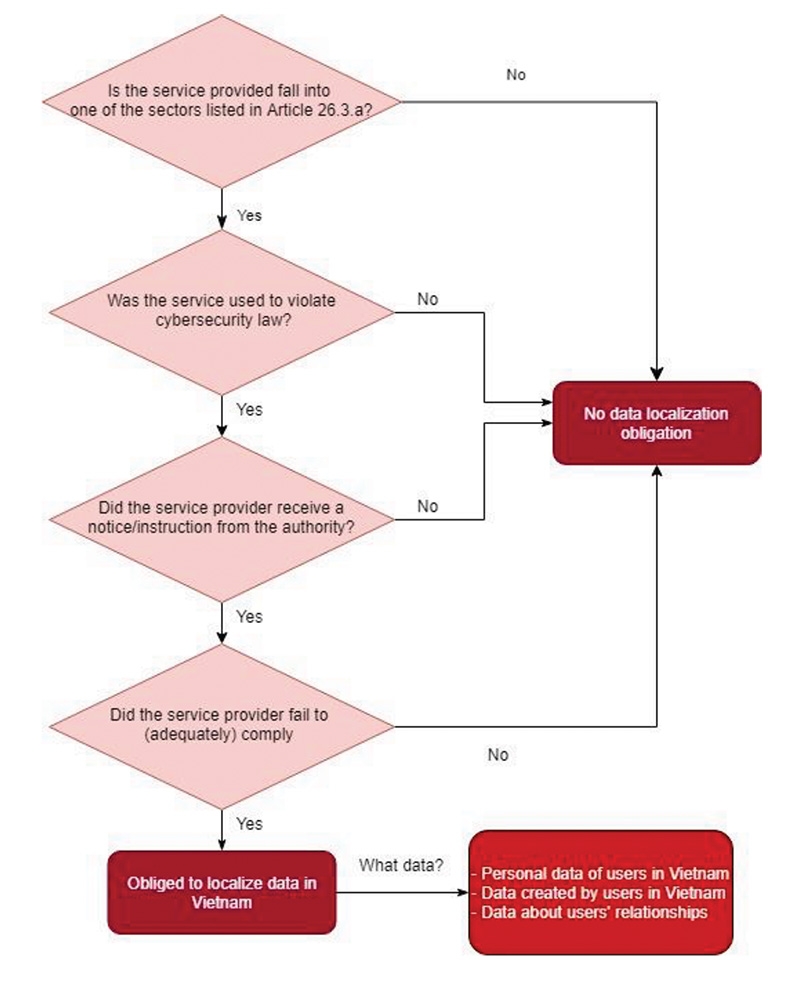

Secondly, Article 26 of the draft cybersecurity decree stipulates that only foreign providers of prescribed services (domain name service, e-commerce, online payment, social network and social communication) may be required to store data and set up a branch/representative office in Vietnam.

Additionally, that obligation only arises if the service has been used to violate the Law on Cybersecurity; such violation(s) has been notified to the service provider by the authority; and the service provider has not complied with such instructions.

In contrast to the Law on Cybersecurity’s preemptive approach, the cybersecurity decree takes a reactive one. Not all offshore service providers have the localisation obligation, only those who have been notified of a breach and fail to comply do. Furthermore, while the Law on Cybersecurity imposes the localisation obligation on all online service providers, under the cybersecurity decree, only foreign providers of listed services may have such an obligation.

Under Vietnamese law, should there be conflicting provisions, the law prevails, so it is interesting to see how the final version of the decree resolves this matter.

The last legislation relating to data localisation is the draft personal data protection decree (PDPD). Under Article 21.1, an enterprise may only transfer data abroad if it meets all of the stipulated requirements, including storing the original data in Vietnam. However, should the exceptions in paragraph 3 apply, the enterprise is exempted from such requirements.

It is unclear whether only one or all four requirements under paragraph 3 must be satisfied for the enterprise to enjoy the exemption, and even so, whether the enterprise is relieved from all or just one of such obligations.

One can draw four remarks from this analysis. Firstly, although the cybersecurity decree, the Law on Cybersecurity and the PDPD all concern “personal data,” their approaches are significantly different. Secondly “storing of data” may be construed to include the storage in processing centres in Vietnam or the storage in third-party storage service providers’ systems. Last but not least, in Vietnam, with respect to certain business activities and especially novel ones, the law may be interpreted to permit only acts that are “approved,” “explicitly permitted,” or “licensed.”

This means that as long as current regulations on data localisation remain conflicting, there is no clear legal basis for businesses to ensure full compliance with the laws.

|

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Tag:

Tag:

Themes: Digital Transformation

- PM sets five key tasks to accelerate sci-tech development

- Ho Chi Minh City launches plan for innovation and digital transformation

- Dassault Systèmes and Nvidia to build platform powering virtual twins

- Sci-tech sector sees January revenue growth of 23 per cent

- Advanced semiconductor testing and packaging plant to become operational in 2027

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- PM sets five key tasks to accelerate sci-tech development (February 26, 2026 | 08:00)

- Canada trade minister to visit Vietnam and Singapore (February 09, 2026 | 17:37)

- New tax incentives to benefit startups and SMEs (February 09, 2026 | 17:27)

- Vietnam forest protection initiative launched (February 07, 2026 | 09:00)

- China buys $1.5bn of Vietnam farm produce in early 2026 (February 06, 2026 | 20:00)

- Vietnam-South Africa strategic partnership boosts business links (February 06, 2026 | 13:28)

- Mondelez Kinh Do renews the spirit of togetherness (February 06, 2026 | 09:35)

- Seafood exports rise in January (February 05, 2026 | 17:31)

- Accelerating digitalisation of air traffic services in Vietnam (February 05, 2026 | 17:30)

- Ekko raises $4.2 million to improve employee retention and financial wellbeing (February 05, 2026 | 17:28)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version