How Dave Cote got Honeywell's groove back

|

| Dave Cote in a New Jersey lab where Honeywell is developing a new nylon copolymer that can be used in food packaging. Around his office he typically wears jeans instead of a suit. |

Dave Cote is feeling the beat. He takes a sip of Mountain Dew and bobs his head in time to the throbbing bass of Jay-Z's "Hard Knock Life." The CEO of Honeywell International, one of the world's largest industrial conglomerates, with $37.1 billion in sales, is wearing his usual work attire -- a beat-up leather bomber jacket, baggy jeans, and clunky work boots. Cote's office in the company's frozen-in-the-1960s headquarters in Morris County, N.J., is nothing fancy. Boston Red Sox jerseys adorn the walls, and a 210-gallon fish tank he inherited gurgles in the background. But for inspiration, he turns to his iTunes and hits SHUFFLE. "I've got 10,000 songs on my server," he says. "The music never stops!"

Neither does Cote. While tunes like Billie Holiday's "God Bless the Child" and Neil Diamond's "Forever in Blue Jeans" play in the background, Cote leaps from his personal history to business insights as nimbly as the music changes genres. You can hear Cote's New Hampshire upbringing in his voice as he recounts his youthful adventures as a cod fisherman in Maine. Moments later he's explaining the technology of turbochargers. Then he veers into his service on the Simpson-Bowles deficit commission in 2010. "What amazed me is how bad future deficits will be even if we have strong growth," warns Cote.

Cote (pronounced CO-tee) is an increasingly rare commodity in the business world: an independent thinker who's the antithesis of a slick, prepackaged CEO. The 59-year-old fills a room not because he's an imperial type who prizes pomp, but because he's a rough-hewn leader who demands accountability. Says Honeywell director Gordon Bethune, former CEO of Continental Airlines: "He took us from a disaster to a hell of a company. And he never beat his chest while he was doing it."

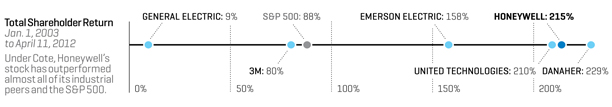

Indeed, Cote, who recently logged his 10th anniversary as CEO, has orchestrated one of the best corporate comebacks in recent memory. Today Honeywell (HON) ranks as a top performeramong the diversified industrials, starting with how it has rewarded shareholders. Since the start of 2003, Honeywell's stock has surged from $24 to $60. Investors have reaped a total return, including dividends, of 215%. That puts Honeywell in second place among industrial conglomerates -- just behind Danaher (DHR), which returned 229%, and ahead of United Technologies (UTX), which has returned 210%. Honeywell's returns wax those of Emerson Electric (EMR) (158%), 3M (MMM) (80%), and Cote's alma mater, GE (GE) (9.4%). In the same period the S&P returned 88%. "Cote has transformed Honeywell into a technology company with strong growth," says Jim Cramer, the CNBC host and former hedge fund manager who also happens to be Cote's next-door neighbor in tony Summit, N.J. "This is one of the great CEOs of our time, yet he's stayed below the radar."

Honeywell: No. 77 on the Fortune 500

How has Cote managed to recharge the failing institution that was Honeywell? The first impression of a relaxed, hip-hop-loving raconteur is misleading. It masks a hard-core work ethic that astounds his friends and lieutenants alike. "I'd call him for dinner in Washington the night before a deficit commission meeting, and he'd say, 'I have eight hours of reading to prepare,' and it would be 6 p.m.!" recalls Tim Collins, CEO of private equity firm Ripplewood Holdings. In a decade Cote has relentlessly transformed Honeywell, making 70 acquisitions and shedding 40 businesses.

That process has shifted Honeywell's portfolio toward game-changing, technologically sophisticated offerings that boast high margins and rapid growth. Honeywell's biggest pillar is automation and controls, a business Cote has recharged with acquisitions including state-of-the-art gas-detection device makers. Ranking second is aerospace. Honeywell is one of the world's largest producers of jet engines for business aircraft, and of advanced avionics for every type of plane. It's also a major innovator in the auto industry through a pet product of Cote's, turbochargers.

The lineup reflects the big ideas that Cote has used to reshape Honeywell. "To run a diversified manufacturer, you need unifying themes," he says. Cote's themes are energy efficiency, energy generation, and industrial safety. "Energy is a conundrum," says Cote. "The economy as a whole will use a lot more of it, but people driving cars and owners of commercial buildings and refineries will want to conserve."

Cote's great accomplishment is unifying Honeywell's formerly fractured, dispirited culture, and at the same time charting a fresh strategy based on those marquee ideas. Doing both required a combination of personal magnetism and forward-looking, often contrarian thinking. The Cote story is a step-by-step primer in an industrial revival that was anything but ordained, at a company that on the day he arrived seemed headed for disaster.

To gauge Cote's accomplishment, it's crucial to understand the mess he inherited. Today's Honeywell descends from a disastrous merger. In late 1999, AlliedSignal purchased Honeywell for $14.4 billion, taking on the latter's more prestigious name. Both companies had big reputations. Honeywell was a stalwart of American manufacturing, named for turn-of-the-century plumbing entrepreneur Mark Honeywell and famous for its iconic round thermostat. AlliedSignal was a scrappy, acquisitive conglomerate run with ruthless efficiency by the legendary Larry Bossidy, the former vice chairman of GE.

Instead of meshing operations and paring costs, the new CEO, Honeywell veteran Mike Bonsignore, and Bossidy, by then chairman, mainly fought. "Larry was always 15 minutes early for meetings and hated to be kept waiting," recalls an executive who is still at Honeywell. "Mike was always 15 minutes late. By the time the meeting started, Larry would be steaming."

By mid-2000 the merger's promise was collapsing, along with Honeywell's profits and share price. Out of desperation the board accepted a takeover offer from GE's Jack Welch. GE teams swooped down on Honeywell. GE executives took over budget planning and employee reviews. But the biggest acquisition in GE history, and what Welch viewed as his crowning achievement, wasn't to be. In June of 2001, Mario Monti, the European Commission's competition chief and now Italy's Prime Minister, effectively killed the merger.

Bonsignore departed, and the board brought back Bossidy to help repair the damage. Bossidy's priority was finding a successor who could handle the challenge. He took a chance on a candidate who'd excelled but hardly proved a superstar at GE, and had served just a year as CEO of TRW (TRW), an auto parts manufacturer half the size of Honeywell: Cote.

Cote's early life is an unlikely prologue for commanding an enterprise of 132,000 employees. He grew up in a New Hampshire mill town named Suncook. His father had an eighth-grade education and ran a garage. "I didn't know what success was, because it was hard to find anyone in town you'd describe as successful," recalls Cote.

But his aptitude for numbers emerged early. "When Dave was 12, I'd put him on the bus to Manchester with his big accordion and some cash," says his mother, Georgette Cote. "After his music lesson he'd go all over town paying all the bills, for the department store, for our insurance." Dave invariably returned with the correct change and all the receipts, Mrs. Cote notes proudly. Today Cote describes himself as "New Hampshire cheap." Declares his mom: "I didn't believe in allowances. When my children asked for money, I'd tell them, 'I don't charge you kids for breakfast!'"

After graduating from high school in 1970, Cote put wanderlust before higher education. He bought a 1963 apple-green Pontiac Catalina for $395 and drove to Michigan, where he labored as a car washer and carpenter's apprentice. The next summer he signed up to join the Navy but backed out of his pledge and decided to try college instead -- talking his way into the University of New Hampshire in Durham even though it was past the official admissions date.

He later took a break from school that wasn't exactly a junior year abroad: Cote and a friend bought a 33-foot lobster boat and spent a year running trawls for cod in Maine. "It taught me that you can work very hard and get absolutely nowhere," he says. Around this time Cote got married and his wife became pregnant. So he sold the lobster boat, and in 1976 he finally graduated from UNH. (Cote is twice divorced and has three adult children and three grandchildren.)

Cote's friends today swear he's the same gregarious, up-for-anything kid from New Hampshire outside the office. The CEO tools around the New Jersey suburbs on weekends on a Harley-Davidson. Or, shotgun in hand, he stalks duck and pheasant in the Adirondacks with his friend Tim Collins. "He's an incredible shot," marvels Collins. "Maybe not the best I've ever seen, but the best for someone running a global corporation."

He also doesn't place too much emphasis on appearances. Cote goes to board meetings in jeans, and encourages the directors to dress likewise. Not all his friends appreciate the look. "I'm a suit-and-tie guy," says Cote's pal, Washington attorney Vernon Jordan. "I'd never come to work in jeans. I tell Dave he looks like something out of Silicon Valley."

While at UNH, Cote had worked the night shift at a nearby GE jet engine plant as an hourly laborer. In 1976 he landed a full-time job at another GE factory in Massachusetts as an internal auditor, making $13,900. Cote rose to join the GE audit staff, then spent the mid-1980s as a financial analyst at headquarters in Fairfield, Conn.

More: Where Honeywell makes its money

It was a chance encounter with chairman Jack Welch in 1985 that propelled Cote's career. Welch heard that the company was dispatching exhaustive questionnaires about GE's business metrics to obscure corners of the world like Mauritania. Regarding this as a colossal waste of time, a furious Welch started calling everyone from the CFO on down, getting madder and madder when he found the brass were absent, until he finally reached the wonk who was handling the project -- Cote. Cote kept his cool, explaining he was doing his best at a job he'd been assigned, then called his wife and said, "I think I'm going to get fired."

But Welch was impressed with Cote's air of authority and his refusal to bad-mouth his superiors -- especially when he later learned that Cote himself had argued against the project. Cote became a Welch favorite. "At GE, if you moved up two levels it was great," says Cote. "Jack promoted me three levels, which was incredible."

In 1996, Cote was put in charge of one of GE's major businesses -- appliances. "Prices were falling, and the appliance field was brutally competitive," recalls Cote. To wring savings in labor, Cote moved some manufacturing jobs to Mexico and threatened to move more. The tactics didn't endear him to the unions. Asked about Cote, Charlie Smith, then head of the Electronic Workers local, wrote to Fortune in an e-mail, "My father used to tell me that if you can't say anything nice about someone, don't say anything at all."

Though Welch prized Cote, it was clear by 1999 that Cote didn't have a shot to be Welch's successor. "Dave wasn't really in contention; he was a ways back," says Welch. So Cote joined TRW as heir apparent, serving briefly as CEO before taking the far bigger job at Honeywell in February of 2002.

For Cote, job one at Honeywell was halting a raging clash of cultures. Employees called it the "red" and "blue" wars, taken from the traditional logo colors of the two companies. Red represented the old Honeywell. Its folks were courtly and prided themselves on pleasing the customer. But in practice that meant promising the customers anything, then, say, infuriating aircraft manufacturers by delivering avionics equipment way behind schedule. Blue stood for the former AlliedSignal. Its ethos was in-your-face confrontation, with an emphasis on "making the numbers" at all costs.

To make matters worse, a third wayward culture needed taming. Around the time of the merger, Honeywell absorbed a maker of fire and safety systems named Pittway. Its managers were staunchly independent folks who'd started their own businesses and considered the red and blue factions too incompetent to give them orders.

The feuding red, blue, and Pittway camps all bristled at taking direction from a new CEO. "I held a town hall meeting in Brussels for the heads of the businesses in Europe," says Cote, "and about one-third of the people I'd invited didn't show up." Pittway, meanwhile, had its own credit cards and initially refused to switch to the brand used by the other employees.

Cote in an Agusta Westland AW139 helicopter. Honeywell is one of the world's largest manufacturers of cockpit controls.

Early on Cote made two pivotal decisions that announced a new kind of leader. First, he ended a long-standing tradition, inherited from both the former Honeywell and AlliedSignal, of aggressive accounting, a practice highly in vogue at the time. Honeywell was capitalizing the cash spent on providing free brakes, wheels, and other parts to airlines to win orders. It was also capitalizing much of its outlays on aerospace R&D. "The system encouraged executives to give away a lot of equipment and do research for its own sake, because those costs looked 'free,'" says Tim Mahoney, chief of the aerospace business. Cote adopted conservative bookkeeping by expensing both types of spending in the current quarter, even though the practice pounded short-term earnings.

Second, Cote introduced a new strategy for tackling Honeywell's destructive legacy -- giant asbestos and environmental liabilities. The former AlliedSignal had taken a stubbornly hard line on asbestos suits, and investors dreaded what the future expense would be. "Dave realized we couldn't litigate our way out," says general counsel Kate Adams. "He decided to take a cooperative approach." Honeywell is establishing a trust for the claims and is working to scrub the soil at old chemical plants. "The key change is that the future expense is now predictable," says Susan Kempler, a portfolio manager at TIAA-CREF, which holds 1.5% of Honeywell's shares. Today the asbestos-plus-environmental expense consistently runs around $150 million a year after-tax. That's a highly manageable number given last year's free cash flow of $3.7 billion.

To unite the company's warring factions Cote also introduced a series of disciplines covering every business. A prime target was manufacturing. Cote saw that labor costs for everything from aircraft power generators to fire alarms were far higher than those of competitors -- a situation he couldn't abide. He added an extra dimension to create what's now the revered Honeywell Operating System, or HOS. Cote demanded that his troops replicate Toyota's manufacturing practices -- in Cote's mind, the best in the world. He dispatched 70 managers to Toyota's plant in Georgetown, Ky., to master techniques for speeding output with the leanest workforce possible.

The rewards have been spectacular. Since 2002, Honeywell has increased its headcount just 21%, vs. an increase in sales of 72%. By keeping fixed costs like labor relatively flat, Cote generates "operating leverage" that magnifies brisk revenue growth into outsize earnings. Since 2003, Honeywell has lifted sales 7% a year, while operating profits have grown by 12%.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Businesses ramp up production as year-end orders surge (December 30, 2025 | 10:05)

- Vietjet chairwoman awarded Labour Hero title (December 29, 2025 | 13:06)

- How to unlock ESG value through green innovation (December 29, 2025 | 10:03)

- AI reshapes media and advertising industry (December 29, 2025 | 08:33)

- FPT and GELEX sign deal to develop blockchain tech for global markets (December 29, 2025 | 08:29)

- Vietnam’s GDP forecast to grow by 9 per cent in 2026 (December 29, 2025 | 08:29)

- Women entrepreneurs are key to Vietnam’s economic growth (December 29, 2025 | 08:00)

- Vietnam's top 500 value-creating enterprises announced (December 27, 2025 | 08:00)

- The PAN Group shaping a better future with ESG strategy (December 26, 2025 | 09:00)

- Masan Consumer officially lists on HSX, marking the next phase of value creation (December 25, 2025 | 13:20)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version