Restructure plan to cap state control

|

| Vietnam needs to restructure its state sector to raise the economy’s growth potential Photo: Le Toan |

Over the past few years, the government has pointed to the restructuring of state-owned enterprises as one of the three pillars of restructuring the economy.

But Dr. Nguyen Dinh Cung, head of the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM), claims that addressing the inefficiencies of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is not enough. He believes the first pillar of the restructuring plan must be about restructuring the entire state-owned sector.

Without changes in the state’s apparatus, functions, and role, Cung said, as well as budget utility and discipline, Vietnam’s goals to restructure other sectors – like public investment and the banking system – will not be feasible.

“The core problem is that current state management is not in line with market signals. This is the reason behind the mistakes and distortions in the allocation of resources in the past,” he told VIR.

CIEM has been designing Vietnam’s 2016-2020 economic restructuring plan. Cung’s point of view has been reflected in the draft plan for the new five-year period, now under National Assembly discussion.

A new growth model

In the 2011-2015 economic restructuring plan, the need for restructuring SOEs was addressed, while reform of the state sector was overlooked.

Vietnam has been among the fastest-growing economies in the world since 1990, reaching middle-income status in 2010. Economic growth, however, tailed off from an average rate of 7.01 per cent during 2006-2010 to 5.9 per cent during 2011-2015, due to slow-moving structural reforms and global uncertainty.

The existing obstacles in the economy caused by the state’s commercialisation via its order-based directions and SOEs have prompted the need to restructure the state sector, including SOEs.

The National Assembly is now debating the country’s national economic restructuring plan for the 2016-2020 period, with a new growth model featured by a major focus on re-allocating and effectively exploiting the country’s resources, and boosting and reforming public investment, banking, and the SOE sector.

Under a scenario for economic restructuring through 2020 compiled by the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI), the average annual growth rate would be 6.86 per cent, with an average annual budget deficit of 4.89 per cent.

Minister of Planning and Investment Nguyen Chi Dung said, “The state’s management will be comprehensively renewed, with the strong reform of all economic institutions, and the construction of a more business-friendly government. The state’s role as a trader and direct investor will be reduced, so that the market will be able to play a bigger role in mobilising and allocating all resources.

“Along with more space created for private enterprises, all state capital at SOEs will be totally divested from the sectors where a 50 per cent stake does not need to be held by the state. By late 2020, the total asset value of SOEs whose 50 per cent stake is held by the state will be reduced to $120 billion [from $365 billion late last year].”

Under the new economic growth model, the growth rate of labour productivity will annually rise 5.5-6 per cent, from an annual average of 2.3 per cent in the past 15 years.

The total factor productivity (TFP) will occupy 30-35 per cent of GDP, instead of the existing 25 per cent. TFP is a measure of the efficiency of all inputs to a production process. Increases in TFP result usually from technological innovations or improvements. In developed nations, the rate averages at 50 per cent. Moreover, the economy will see more enterprises with hi-tech application and research and development activities. According to the Vietnam 2035 report, a joint Vietnam-World Bank Group study, which discusses the path for Vietnam to reach upper-middle-income status in two decades, improving productivity is essential for the country to reach upper-middle income status by 2035.

|

Slack SOE reform

Adam Sitkoff, executive director of AmCham Hanoi, told VIR, “Vietnam’s restructuring of the state sector is critically needed, and it is also time to move forward with the difficult task of restructuring SOEs to ensure they are managed with transparency, responsibility, and accountability – and that SOEs operate on a ‘level playing field’ with both foreign and domestic private sector enterprises.”

The Ministry of Finance reported to the National Assembly that Vietnam’s SOE reform has been progressing at a snail’s pace.

From 2011 to late September 2016, 557 enterprises had their equitisation plans approved. However, only 426 have completed their initial public offerings – of which only 254 could sell their stakes under the approved equitisation plans, with a total value of $1.97 billion. Currently Vietnam has more than 650 SOEs that have yet to be equitised.

Last year, the total debt of parent SOEs in Vietnam was $39.22 billion, up 5 per cent year-on-year. The total foreign debts of state-owned groups and corporations reached $15.83 billion.

“SOE restructuring has failed to significantly reduce the state’s direct commercialisation in the economy,” Dung said. “The capital collected from SOE restructuring remains very small as compared to the total capital that the state has invested in enterprises. Thus the government has failed to reach its target to re-allocate the economy’s resources.”

Specifically, from 2012 to October 2015, SOE divestment brought about VND22.87 trillion ($1.04 billion) into state coffers, equal to only 2 per cent of the total state capital in enterprises.

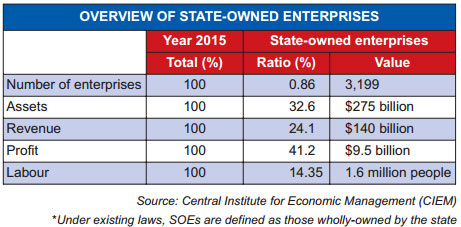

By late 2015, the total asset value of SOEs in which 50 per cent of stake is held by the state was $365 billion, tantamount to 188 per cent of the GDP and 33.32 per cent of the total asset value of all enterprises in Vietnam.

“Vietnamese SOEs’ total asset value is much bigger than that the $100 billion limit for SOEs in each of the countries within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, while Vietnam’s economic scale is much smaller,” Dung said.

Prof. Tran Ngoc Tho from Ho Chi Minh City Economics University said that though SOEs are trying to sell their stake, the stake sold to private enterprises is negligible. “With the existing cross-ownership SOE system, SOEs will remain SOEs after equitisation.”

According to the World Bank, Vietnam is facing state effectiveness challenges. Specifically, the commercialisation of state institutions, their excessive fragmentation, few checks and balances within the government, and the limited participation of citizens are seriously hurting the economy’s competitiveness.

Vietnam has been actively engaging in economic activity directly through SOEs, particularly through large state economic groups, and indirectly through close links between the state and an exclusive segment of the domestic private sector.

“Vietnam is not alone in having influential vested interests, but the degree to which relationships to the state are integral to economic success appears to be unusually high,” stated the Vietnam 2035 report.

Beyond its costs to the economy, commercialisation of state institutions weakens the effectiveness of the state itself. “It creates powerful incentives for public officials to exploit their regulatory powers and allocations of property rights to lock in long-term benefits for themselves, their families, or their networks. Such abuses of public authority undermine the legitimacy of state institutions,” noted the report released in February 2016.

Prospects

Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc recently told leaders of 150 global firms at the World Economic Forum in Hanoi, “We will restructure the state sector’s investment capital portfolio and assets, foremost in SOEs. We will transfer commercial assets and business opportunities to the private sector. All capital from equitisation will be used for building infrastructure and improving social welfare.”

AmCham’s Sitkoff points to the greater effort needed in solving the continued challenges of corruption, human resource constraints, and an over-complicated, restricted, and unclear licensing and regulatory environment. “A new reform effort is required to promote long-term economic growth in order to create jobs, wealth opportunities, and a better standard of living here,” he said.

“Vietnam has a great opportunity to build a modern, efficient economy.”

Commenting on Vietnam’s prospects, the International Monetary Fund said in a report on the country’s economy that a second generation of reforms is needed to mitigate risks and raise the economy’s growth potential. Medium-term growth will be challenged by low productivity in the domestic economy, and demographic headwinds will emerge in the longer run. Against this backdrop, the new government’s commitment to reforms is encouraging. “Accelerating and broadening fiscal, monetary, banking, and structural reforms would place Vietnam in a sound position to achieve the authorities’ medium-term growth target of 6.5-7 per cent.”

CIEM’s Cung said the economy can annually grow by 6.5 per cent if the state sector is reformed effectively, and even by 7 per cent if budget discipline is strictly ensured.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

- 14th National Party Congress wraps up with success (January 25, 2026 | 09:49)

- Congratulations from VFF Central Committee's int’l partners to 14th National Party Congress (January 25, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th Party Central Committee unanimously elects To Lam as General Secretary (January 23, 2026 | 16:22)

- Worldwide congratulations underscore confidence in Vietnam’s 14th Party Congress (January 23, 2026 | 09:02)

- Political parties, organisations, int’l friends send congratulations to 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:33)

- Press release on second working day of 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:19)

- 14th National Party Congress: Japanese media highlight Vietnam’s growth targets (January 21, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th National Party Congress: Driving force for Vietnam to continue renewal, innovation, breakthroughs (January 21, 2026 | 09:42)

- Vietnam remains spiritual support for progressive forces: Colombian party leader (January 21, 2026 | 08:00)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version