Mitigating procedural delays in pharmaceutical market

|

| Ngo Thanh Hai, senior associate at LNT & Partners |

Today, there are clearer provisions on the rights and duties of pharmaceutical business establishments (PBEs). Article 32 of the Law on Pharmacy 2016 provides an exhaustive list of all recognised pharmaceutical business activities, among which clinical trial services and bioequivalence study services are two new additions under the 2016 legislation. Enterprises that conduct any listed pharmaceutical business activity will be considered a PBE.

All PBEs enjoy the general rights stipulated under Article 42 of the pharmacy law. Compared with the 2005 iteration, the 2016 legislation expressly permits PBEs to conduct drug information and advertising activities, as well as to provide free drugs to patients via patient assistance programmes at healthcare establishments. The specific rights and obligations of each type of PBE are further elaborated in Articles 43-53.

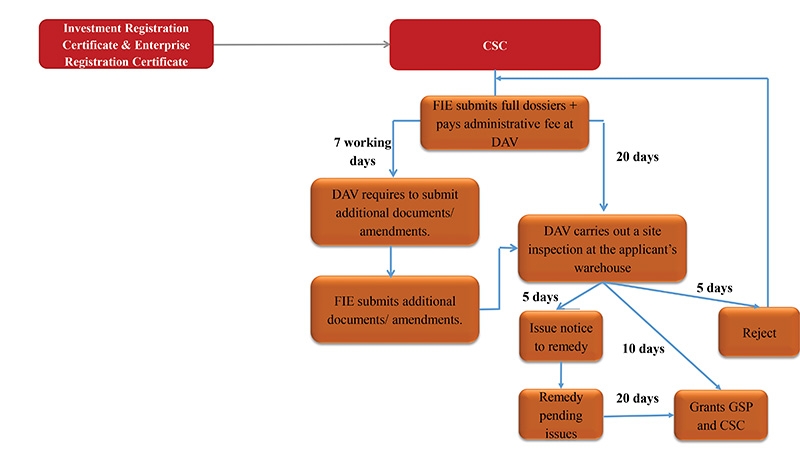

Foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) enjoy drug import-export rights. Procedures to obtain the certificate of satisfaction of conditions for drug-importing business (CSC) are clear and the timeline in practice is relatively short. FIEs’ rights to import and export drugs are recognised for the first time under the pharmacy law. Article 44.1(d) thereof provides that “If [an importer] is not allowed to distribute imported medicinal products or ingredients in Vietnam, they shall have the right to sell these products in accordance with the regulations of the Ministry of Health (MoH)”.

Based on our experience advising several pharmaceutical FIEs, the CSC application procedure is clear and in practice could be 3-4 months shorter than the statutory timeline.

These changes introduced by the Law on Pharmacy and Decree 54/2017/NĐ-CP released in 2017 on guiding the implementation of this law were instrumental to the fight against COVID-19 as they provided the legal framework for FIEs to import vaccines into the country. LNT & Partners has advised AstraZeneca Vietnam in obtaining the CSC to import the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine into Vietnam, and Moderna on its vaccine shipment which will be imported and supplied to the government by Zuellig Pharma.

The Law on Pharmacy 2016 has reduced some admin burdens for enterprises by removing the obligation to renew the CSC. However, the authority will assess operation of the licensed enterprise every three years and may revoke the license if it fails to uphold the applicable requirements. Furthermore, the law does not require manufacturers to apply for a permit to import medicinal ingredients if they are used to manufacture drugs which already have authorisation.

The law also introduces price negotiation as a new mechanism to procure branded drugs, rare drugs, off-patent drugs, drugs with uncommon ingredients, and other special cases. In 2018 – the first year price negotiation was implemented for branded drugs – the aggregate price reduction was reportedly $24 million, or 18.55 per cent. However, this change has caused significant disruption to a number of branded drug manufacturers, especially when hospitals are reluctant to procure branded drugs until receiving further guidance from the MoH. LNT has been advising an industry association representing a large number of pharmaceutical multinational corporations in Vietnam in working with the MoH to resolve the matter. The association’s relentless efforts eventually paid off when the MoH issued official guidance allowing hospitals to procure branded drugs as usual pending the release of price negotiation results.

|

Issues to resolve

There are restrictions on FIEs’ rights to carry out drug storage and transportation services. Under Article 91.10 of Decree 54, foreign-invested drug importers are prohibited from taking part in distribution-related activities including drug storage and delivery services to local partners.

This provision, however, is not consistent with either the Law on Pharmacy, Vietnam’s World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments or any other local legislative documents. Specifically, Article 32 of the pharmacy law recognises storage service as a separate pharmaceutical business activity, independent from distribution services.

In addition, as per Section 4 under Part II of Vietnam’s WTO commitments on services, distribution activities do not apply to pharmaceuticals. However, Section 11 under Part II does not prohibit foreign investors from carrying out warehousing business and freight transport services by road, permissible via a joint venture with a local partner where the foreign capital contribution ratio does not exceed 51 per cent. Decree No.09/2018/ND-CP effective from the start of 2018 also clearly stated that goods distribution activities do not include goods storage and transportation services.

The storage and transportation services are logistics services as mentioned in WTO commitments and according to Article 233 of the 2005 Commercial Law: “Logistics services are commercial activities whereby traders organise the performance of one or many jobs including reception, transportation, and warehousing”.

Such restrictions under Article 91.10 of Decree 54 not only negatively affect FIEs, especially those which were allowed to do those services in the past and had thus invested substantially in warehousing and delivery systems, but also shift the burden to local companies which would have to increase investment in building their own warehouses and delivery truck network. This may in turn increase the cost per prescription and eventually be passed on to patients in the form of higher drug prices.

Meanwhile, market authorisation (MA) registration is too time-consuming. Article 56.5 of the Law on Pharmacy 2016 sets the time limit for issuing MAs at 12 months from receipt of a full and valid application for new drug products and three months for renewal. However, in practice, the time taken to obtain it is usually more than one year. It is estimated that only 8 per cent of more than 2,000 new MA application dossiers were successful.

Another challenge is that many MAs of medicines used in the treatment of acute or chronic illnesses will expire and may severely affect the lives of many patients. It is estimated that out of over 1,000 renewal dossiers submitted, only about a quarter received approvals.

There are a number of reasons for this delay, from short-term challenges such as the current pandemic, to more fundamental issues such as the fact that experts who appraise the registration dossiers work on a part-time basis, or the Drug Registration Office’s chronic understaffing problem which is exacerbated by the large volume of submissions.

Elsewhere, there is unclear guidance on contract manufacturing organisations. The Vietnamese government’s policy is to promote local manufacturing to reduce the dependence on imports. Since the government wants local production to meet 80 per cent of the domestic demand, pharmaceutical companies that are currently importing and selling drugs are expected to partner with local manufacturers. However, the law only permits manufacturers to engage in processing services, whereas there is no legal framework for FIE importers to do the same.

Although Circular No.23/2013/TT-BYT enacted in 2013 on guiding drug processing permits any “drug business establishment” to engage in processing services, this is no longer applicable as the terms “drug business establishment” and “foreign drug business and manufacturing establishments that have “operation permit of foreign enterprises on drugs and drug materials in Vietnam” have been eradicated under the 2016 law (which instead adopted the wording “pharmacy business establishment”). Currently, no replacement circular on this important matter has been issued.

Other unclear regulations include those on restrictions applicable to FIEs under Article 91.10 of Decree 54. It is difficult for FIEs to determine whether their operations are in line with this or not. For instance, FIEs are not allowed to provide financial assistance to buyers of medicinal products to control the distribution of imported drugs, or to do other activities related to drug distribution. The general wording of the provision makes it difficult to tell whether FIEs are prohibited from giving discounts or other promotions to the buyers.

Finally, deadlines and criteria for price negotiation need to be clearer. Only four out of 701 branded drugs have received price negotiation results. The delay is partly due to the extensive time needed to formulate clear criteria and grounds to negotiate drug prices. Although the MoH has set out a number of price negotiation bases in Circular No.15/2020/TT-BYT (Article 5.4), they are only basic principles and require further elaboration from a drug price negotiation council. However, such a council has not been established.

Recommendations

To mitigate the procedural delay, the MoH may consider taking the entire registration process, from submission to review and approval, entirely online in order to simplify it. There should also be more staff on dossier review duty to address the manpower shortage and consequent backlog. The MoH may also consider increasing the registration fee to finance the recruitment of additional personnel. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that there is no conflict between legislative documents. Specifically, if Article 91.10 of Decree 54 contradicts the Law on Pharmacy and other laws, the article should be amended. The restrictions stipulated under this provision also need to be clarified in a MoH circular to avoid an open-ended prohibition clause and to ensure compliance with Vietnam’s fundamental investment principle – enterprises are entitled to carry out any business activities that are not prohibited by laws.

A detailed timeline for price negotiation as well as clear guidance on contract manufacturing operations will also benefit Vietnamese patients significantly. Price negotiation will certainly reduce drug prices and local companies will enjoy greater benefits when there is a clear legal framework for FIEs to form partnerships with them.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- The wider benefits of digital signatures in e-transactions (April 18, 2022 | 11:31)

- Interpreting new real estate statutes (August 23, 2021 | 09:20)

- Pros of sandbox regulation for fintech (July 09, 2019 | 13:36)

- Wind power barriers need removing (April 02, 2019 | 09:55)

- Advice for foreign home ownership (November 16, 2015 | 08:37)

- Revised legal framework benefits foreign investors (October 26, 2015 | 07:36)

- Important documents regulating bank guarantee (September 19, 2015 | 11:11)

- Law Changes Open up Opportunities in Property Sector But Questions Remain (September 04, 2015 | 11:27)

- Decree eases constraints (July 27, 2015 | 08:48)

- Enterprises scrutinise guidelines on new laws ahead of implementation (July 23, 2015 | 11:06)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version