Keys to nation’s investment optimism

|

| Edmund Malesky - Lead researcher Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index |

Even more surprisingly, considering the current global circumstances, the country managed to attract $8.6 billion in foreign investment during the first quarter of this year, which was nearly 80 per cent of the sum it attracted during the same period last year before the tremendous shocks to the global economy.

Even rosier figures are expected for the rest of the year, now that the country has again opened its doors to economic activity.

So what accounts for Vietnam’s remarkable success?

Some analysts have pointed towards the government’s management of the pandemic, as well as efforts by multinationals to lower dependence of supply chains on China by diversifying to other markets. These are certainly true, but insufficient explanations.

The resilience displayed in combating the virus has little do with investors’ long-term expectations of profitability in Vietnam, and many other countries were available for investors seeking to shift notes in their supply chains.

A long-term analysis of the annual PCI-FDI survey of 1,583 enterprises between 2010-2019, which includes firms from 52 countries investing in 21 Vietnamese cities and provinces, points to three governance trends.

These trends underpin current international optimism about Vietnam’s business environment. These include a remarkable reduction in waiting periods to legally license and register a foreign business in this country; improvements in the accessibility and security of land for doing business in Vietnam; and dramatic reductions in bribe payments in a wide variety of business-government transactions.

Ease of market entry

In 2019, when foreign businesses were asked to reflect on the most important reforms in Vietnam, 55 per cent highlighted reductions in the cost of legally starting a business, outranking all other activities including improvements in infrastructure, labour policy, and tax reductions.

Reductions in entry costs has been a focus of Vietnamese reforms for many years but received a huge lift from the 2014 Law on Investment and its subsequent implementing documents.

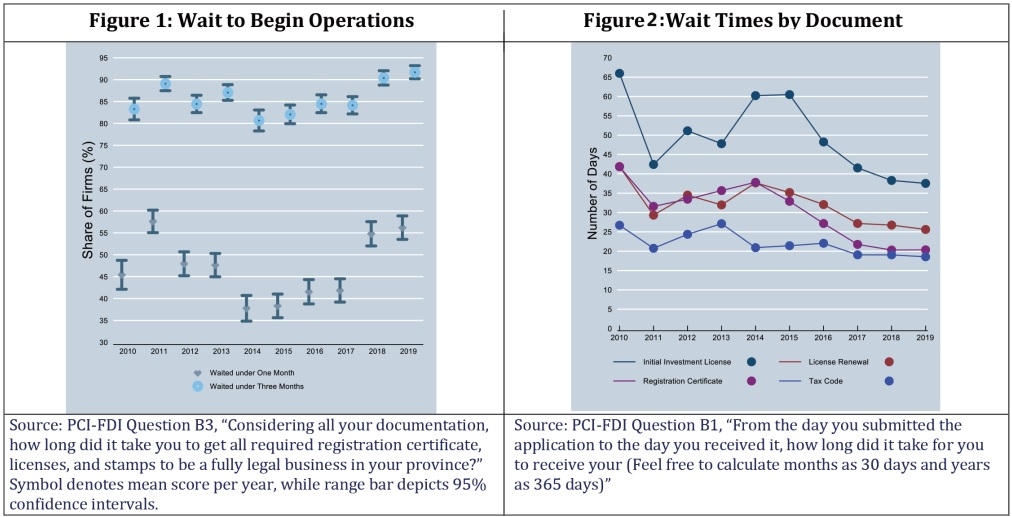

Figures 1 and 2 explore Vietnam’s success on easing business entry. Critically, we observed that in 2014 before the promulgation of the law, 80 per cent of respondents waited under three months to obtain all of the necessary documentation to legally begin business.

By contrast, last year 92 per cent of foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) were fully legal within three months, the highest share observed in the history of the survey.

Since 2015, initial licensing waiting periods have dropped from 60 days on average to less than 40. Registration certificate waits have dropped from an average of 36 days to 20 days, licence renewals have declined from 35 days to 25 days, and tax code acquisition has declined from 22 days to just under 20 days.

In sum, regulatory improvements have saved businesses 38 days in business start-up time, a shocking 27 per cent decline in the costs of entry for FIEs across the country.

It is quite clear why FIEs are so pleased with changes made in business establishment procedures. Importantly, the lowest entry costs are experienced by a new legal form of FIE created by the 2014 Law on Investment, which allowed FIEs with 50 per cent local ownership to enter as domestic private operations.

Expropriation risk reduction

A critical concern for all in emerging markets is fear of expropriation of their business premises. Such fears keep investors from expanding to the full potential of their business, as they cannot be certain that they will be able to recuperate the full costs of their project. In Vietnam, these fears remain because ownership rights are more complicated than in Western markets. According to Article 53 in the 2013 Constitution and the Law on Land, the Vietnamese people are the ultimate owners of land managed by the state, but businesses can hold long-term leases, called land use rights certificates (LURCs) that allow them to sell, exchange, lease, and mortgage the land.

Foreign investors can obtain LURCs either by partnering with a Vietnamese company (state-owned or private) that provides the LURC as part of its joint venture (JV) contribution, or by leasing directly from state-permitted lessors such as a national or provincial government authority.

Two trends are evident in the PCI-FDI data. Since the promulgation of the 2013 Law on Land, there is a sharp jump in formal LURC possession after the promulgation of the law (from 26.2 per cent in 2012 to a high of 38.8 per cent in 2016), which corresponds with a decline in short-term rentals (from 72.2 per cent in 2012 to a low of 56 per cent in 2016). Since 2017, however, these trends have reversed slightly, which is disconcerting as LURCs represent the most secure documentation.

We probed a historical question, where respondents have been asked to consider the risk of expropriation of their operations. Firms answer on a scale ranging from 1-5 (very low to very high). Before the promulgation of the 2013 Law on Land, the likelihood of expropriation was considered to be moderately high. In 2012, for instance, only 47.1 per cent of firms answered that expropriation risk was low or very low. Immediately after the promulgation of the law however, we see a tremendous change in this perspective.

Businesses in JVs, which represent the very smallest group (only 6 per cent of investors), show the greatest increase over time in their confidence in security of property rights. This is likely due to a belief that the local partner, usually a state-owned enterprise or connected private firm, possesses strong relationships that can lead to informal enforcement.

Businesses obtaining their LURCs within the industrial zone (about 31 per cent of investors) show the next largest rise. By 2019, 85 per cent of firms with certificates rank expropriation risk as low, statistically indistinguishable from those in JVs. By contrast, firms with LURCs outside the industrial zone (32 per cent of investors) have been less confident, averaging around 75 per cent claiming low risk, for most of the post-2013 period.

|

Dramatic bribery drop

Since taking charge in 2016, the new central administration has been aggressively tackling corruption and informal charges in government-business interactions, with policy measures such as Resolution No.35/NQ-CP on supporting the development of enterprises towards 2020. As a further step, Resolution No.139/NQ-CP, issued in 2018, specifies five specific goals to reduce the cost of doing business.

The 2017 and 2018 PCI reports drew attention to significant declines in corrupt behaviour among FIEs. Progress continued and even accelerated this year. While 45.8 per cent of businesses had to pay informal charges to inspectors in 2016, this dropped to 44.9 per cent in 2017, 39.9 per cent in 2018, and reached a low of 32.5 per cent in 2019.

The share of businesses having to pay a bribe during customs procedures declined from 56.4 per cent in 2016 to 42.5 per cent in 2019. More than one-fifth of FIEs paid bribes during land transactions in 2016. In 2019, the number rose more than three percentage points above the 2018 level, but remained at less than half the 2016 figure.

One important effect of the reduction in corruption is businesses’ attitude towards regulations. Recent achievements in reducing informal charges have affected FIE’s perception of regulations as an excuse for rent seeking. According to our findings, the share of FIEs agreeing with the statement that regulations are a pretext for bribery dropped from its 2014 high of 59.9 per cent to a much-improved 33.7 per cent in 2019.

FIEs’ responses on the costs of informal charges did not follow the same declining trend as other indicators. At the end of the last administration in 2015, FIEs paid bribes equal to about 1.69 per cent of their annual sales revenue. This number dropped steadily during the anti-corruption campaign, reaching a low of 1.04 per cent in 2018. In 2019, the bribe cost increased slightly to 1.11 per cent, but remains very low compared with past levels. Moreover, the overlapping confidence intervals indicate the cost of bribery is not significantly different than it was in 2018.

The impact of the anti-corruption campaign on the bottom lines for businesses is significant. Trade economists estimate that export earnings of FIEs in Vietnam was about $181.35 billion. Using this number as a proxy revenue, we can calculate that the unofficial cost of doing business is $1.1 billion lower today than in 2015 – a net saving for foreign exporters that can be productively applied to workers’ salaries, innovation, and even formal domestic taxes.

The bottom line is that Vietnam’s anti-corruption campaign has been successful at reducing the scale of bribery experienced by foreign investors, lowering the financial risk they face by engaging in business in the country.

Newer concerns

Together, these three trends of reduced entry costs, greater property rights, and lower corruption indicate that efforts made by the Vietnamese leadership are clearly transforming the ways foreign investors interact with the state, reducing the costs of doing business and alleviating their fears about regulatory risk. They play a critical role in explaining why 53 per cent of foreign investors report that they plan to expand their business over the next two years in the country.

However, these reforms were crafted for a different generation of FIEs. The country’s own economic growth, burgeoning middle class, and increased technical sophistication, combined with changes in the global economy are incrementally changing the composition of foreign direct investment. In particular, we are seeing greater entry and business expansion by those producing higher technology goods. They will need different sets of policies from the state in order to thrive.

Two areas of particular concern arise from this year’s analysis. First, Vietnam’s regulatory system needs to become more efficient and professional. In general, the regulatory burden (particularly safety and tax audits) is not overwhelming. The median FIEs experience two inspections and 1.5 audits per year. However, a small set of firms, many of them the country’s most dynamic foreign investors, bear an unfair share of the compliance costs.

Second, despite the demonstrable successes of the anti-corruption campaign, bribery does remain relatively frequent in particular areas, such as construction permitting. Using a specialised survey experiment that shields respondents from culpability, we find that 48 per cent of FIEs who applied for construction permits in the past year paid bribes to acquire them at an additional average cost of VND24 million ($1,000) per permit.

Critically, these numbers represent a lower bound because they do not include FIEs that did not apply for new construction licences because they were worried about the additional informal charges.

Vietnamese authorities have shown a willingness to work hard and innovate to improve the investment attractiveness. These efforts have led to more productive operations willing to take larger risks. The next generation of Vietnamese leaders will need to maintain their innovation and reform-minded approach to tackle the new challenges brought by the evolving investment landscape.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

- 14th National Party Congress wraps up with success (January 25, 2026 | 09:49)

- Congratulations from VFF Central Committee's int’l partners to 14th National Party Congress (January 25, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th Party Central Committee unanimously elects To Lam as General Secretary (January 23, 2026 | 16:22)

- Worldwide congratulations underscore confidence in Vietnam’s 14th Party Congress (January 23, 2026 | 09:02)

- Political parties, organisations, int’l friends send congratulations to 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:33)

- Press release on second working day of 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:19)

- 14th National Party Congress: Japanese media highlight Vietnam’s growth targets (January 21, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th National Party Congress: Driving force for Vietnam to continue renewal, innovation, breakthroughs (January 21, 2026 | 09:42)

- Vietnam remains spiritual support for progressive forces: Colombian party leader (January 21, 2026 | 08:00)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version