How GE exorcised the ghost of Jack Welch to become a 124-year-old startup

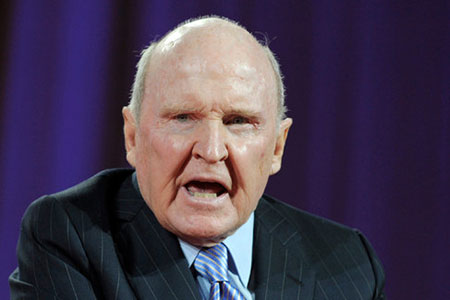

Overlooking the Hudson River in Ossining, N.Y., there’s a grassy, 59-acre campus owned by General Electric. It’s an executive training center where the company holds management and leadership classes, some of them led by the chief executive himself. Jack Welch, who ran GE in the 1980s and ’90s, would arrive by helicopter. He’d make his way to a windowless auditorium known as the Pit where a group of managers waited. They used to call him “Neutron Jack,” because he was known for firing so many people that only the buildings were left standing. Neutron Jack and his executives would engage in an aggressive form of corporate group therapy, raising their voices as they aired their frustrations with the company and each other. Later, they would have drinks at the White House, the campus bar. It drove business magazines wild with excitement. “The class sits transfixed as Welch’s laser-blue eyes scan the auditorium .. , ” wrote Businessweek in 1998.

Today, GE executives sorry, team members take classes in yoga and meditation and suminagashi, the Japanese art of painting on still water. The White House has become a low-key place where visitors can sip artisanal coffee rather than martinis. The Pit has a window through which the sun shines.

|

| Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, March 21, 2016 |

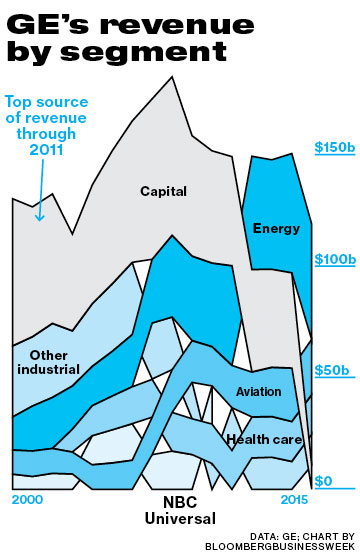

It’s part of a much larger transformation at GE orchestrated by Jeff Immelt, Welch’s successor as chief executive officer. Most notably, GE is moving its headquarters from suburban Fairfield, Conn., land of golf and bonuses, where it’s been since 1974, to Boston, the Athens of America. The company is selling off its division that makes refrigerators and microwave ovens. Now it’s focused on electric power generators, jet engines, locomotives, and oil-refining gear. And it’s made a significant bet on developing software to connect these devices to the Internet. There’s a term for this trend of adding network connections to hardware not usually considered computers: the Internet of Things. GE believes its opportunity lies in what it calls the Internet of Really Big Things.

In the past five years, GE has hired hundreds of software developers, created its own operating system, and fashioned dozens of applications that it says will make planes fly more efficiently, extend the life of power generators, and allow trains to run faster. GE’s plan is to sell this software to other manufacturers of Really Big Industrial Things, and to be a top 10 software company by 2020. That would put it in the same category as Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle.

|

| Immelt at GE’s soon-to-be-former HQ in Fairfield, Conn. Photographer: Jeremy Liebman |

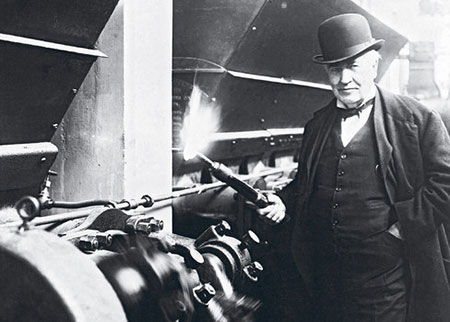

GE is also revising its managerial rhetoric. The company was officially founded in 1892 when Thomas Edison merged his operation with a rival electric light manufacturer. In the 1950s, CEO Ralph Cordiner promoted the theory of decentralisation, which turned 120 business heads into mini-CEOs. In the 1970s, Reginald Jones championed “strategic business planning,” which treated the company’s many ventures as an investment portfolio. As a sloganeer, no one matched Neutron Jack’s ferocity. He was an evangelist for Six Sigma, a numbers-driven quality-control method that he didn’t originate but grabbed hold of and turned into a boardroom craze. He wanted GE to be a “learning enterprise” with “a boundaryless culture.” He also called it “the greatest people factory in the world,” one that welded together managers who could run anything from the plastics division to a television network. (Welch spent several years dispensing management advice in the pages of this magazine a decade ago, after retiring from GE.)

Immelt, who took over in 2001, tried to promote his own management methods. He brought in cultural anthropologists to study employee behavior. He tried to get his executives to submit “imagination breakthroughs” that would galvanise GE and generate growth. GE held “idea jams” to foster creativity.

Nothing seemed to work. GE’s shares were mauled in the recession of the early Aughts. Meanwhile, its GE Capital division morphed into one of the world’s largest providers of commercial real estate debt and aircraft leases. During the financial crisis of 2008, Immelt was forced to seek the protection of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which guaranteed about $60 billion of GE Capital’s debt.

|

| A turbine rotor, which is being hoisted by a giant crane at the General Electric turbine plant in Schenectady, N.Y., on Feb. 21, 1952. The heart of a turbine generator, the rotor weighs 42,200 pounds but has the precision of the finest watch. Photographer: Bettmann/Corbis |

By then, Immelt had seen the share price fall from $60 in 2000 below $6. GE was stripped of its triple-A credit rating by Standard & Poor’s, and Immelt cut the dividend for the first time since 1938. In 2012 this magazine referred to Immelt’s first 10 years as “GE’s Lost Decade” and calculated that investors had seen a total return of zero during his tenure.

But by last fall, Immelt’s programme was beginning to succeed. He had announced a plan to shed $200 billion of GE’s problematic financial assets, which have weighed down its share price. The company says it had software sales of $5 billion in 2015, a sign that the Internet-of-really-big-things approach must be taken seriously. And, by all accounts, Immelt’s campaign to remake the company’s intrinsically rigid culture is working. In the past year, GE’s stock has outperformed the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index.

Immelt started thinking about data. Many of GE’s corporate customers were putting sensors on their machines to collect information about them. That often meant a lot of information: A jet engine, for instance, spits out roughly a terabyte’s worth of everything from fuel usage to heat levels to the size of the specks of dirt that fly through the engine on a trip across America. What were GE’s customers supposed to do with all that data?

|

| Jack Welch and Jeff Immelt at a press conference in New York announcing Immelt as president and chairman-elect of GE on November 27, 2000. Photographer: Mark Peterson/Corbis |

Immelt’s own knowledge of the software business was limited. He graduated from Dartmouth with a dual degree in economics and applied math in 1978. After getting his MBA at Harvard, he turned down a job at Morgan Stanley to work at GE. He ended up running the health-care division in the 1990s, which opened a software center of its own in Wisconsin. Because of that, he says, he knew enough to ask the right questions about software.

He went after William Ruh, then a vice president at Cisco Systems. Ruh found it hard to believe that GE would be willing to invest the kind of money it would take to build a successful software business. Silicon Valley is full of little startups, but creating software at an industrial scale would require billions of dollars. He also couldn’t see GE, with more than 300,000 employees, making the cultural changes needed to compete in the Valley.

|

| Thomas Edison, right, and Dr. Irving Langmuir, center, are shown discussing the vacuum tube at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, N.Y., circa 1904-25. Source: Corbis |

Despite those qualms, he traveled to Fairfield in January 2011 to meet with Immelt. Ruh says he was impressed by Immelt’s vision and his willingness to admit that he didn’t fully know what he was doing. “Basically, Jeff said, ‘Look, we’re on Step 1 of a 50-step process, and I just need you to help me figure out what to do because I can only see out one or two steps,’ ” Ruh says. He took the job, and several weeks later his new boss promised to invest $1 billion in a software operation in San Ramon, Calif.

|

At the end of 2013, GE had 750 people working in San Ramon. By then, GE had developed an early version of Predix, an operating system like Windows or Android but for the Industrial Internet. The company developed applications for Predix enabling it to ingest and analyse vast amounts of data from sensor-equipped machines much like Amazon.com, Facebook, and Google do with information generated by their human customers. Immelt wanted to speed Predix’s development and use it on GE’s own equipment. That meant the entire company had to embrace the new operating system, even the power division, which usually took years to design turbines. There didn’t seem to be much need to rush out new models; GE’s power customers typically buy steam- or gas-powered turbines and use them for three decades.

|

| Jack Welch Photographer: Peter Foley/Bloomberg |

In April 2015, Immelt announced his plan to sell $200 billion of its GE Capital assets within two years, faster than Wall Street had expected. Along with unloading most of its risky financial business, GE struck a deal to sell off its appliance division to Haier, the Chinese conglomerate, and increased its share of the global power industry with its 2015 purchase of Alstom, a French energy company, for $10 billion. As a result, 90 per cent of GE’s profits will come from industrial operations by 2018. (During its glory years from the late ’90s into the mid-2000s, GE Capital contributed as much as 40 per cent.) Immelt says this is the GE he’s been trying to create since the financial crisis, although he acknowledges that it might have been difficult for outsiders to discern.

In January, GE announced the move to Boston, where the deer are few and the software developers plentiful. “Sitting in a rural setting, you can never be scared enough of what’s next,” Immelt says. “You just can’t be. You can’t be paranoid enough. And I felt like it would be a good thing for the business just to be in the flow of ideas.”

Head count at the San Ramon office is 1,300, including some refugees from Google and Facebook. It already has aviation customers using Predix applications to monitor the wear and tear on their jet engines and calibrate their maintenance schedules based on that data rather than an average for the entire fleet. It’s created smart wind turbines that tell each other how to shift their blades to catch more wind, which GE says can increase their power output by as much as 20 per cent.

|

| Thomas Edison lights a new boiler in West Orange, N.J., on Jan. 7, 1919. Source: Corbis |

But Immelt needs to sell vast amounts of applications and Predix-based analytics to reach his goal of making GE a top 10 software company in 2020. That’s not a random deadline. Traditionally, GE chief executives have served 20 years, so his time will be just about up by then. He says the company already has a succession plan in place. If he can complete his digital reinvention of the company, he could depart in glory, the way Welch did.

Not long ago, Immelt gave a speech in Dubai about the Industrial Internet. He wasn’t talking to tech people “with spiked hair,” as he puts it. He was addressing attendees who worked at oil companies and airlines in other words, his kind of people. Immelt could see them nodding their heads approvingly as he talked. “It’s moments like that when you think, ‘This might work,’ ” he says later. “ ‘This really might work.’ ”

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- Vietnamese businesses diversify amid global trade shifts (February 03, 2026 | 17:18)

- Consumer finance sector posts sharp profit growth (February 03, 2026 | 13:05)

- Vietnam and US to launch sixth trade negotiation round (January 30, 2026 | 15:19)

- NAB Innovation Centre underscores Vietnam’s appeal for tech investment (January 30, 2026 | 11:16)

- Vietnam moves towards market-based fuel management with E10 rollout (January 30, 2026 | 11:10)

- Vietnam startup funding enters a period of capital reset (January 30, 2026 | 11:06)

- Vietnam strengthens public debt management with World Bank and IMF (January 30, 2026 | 11:00)

- PM inspects APEC 2027 project progress in An Giang province (January 29, 2026 | 09:00)

- Vietnam among the world’s top 15 trading nations (January 28, 2026 | 17:12)

- Vietnam accelerates preparations for arbitration centre linked to new financial hub (January 28, 2026 | 17:09)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version