High prices call for green transition acceleration

|

| Patrick Lenain Former assistant director Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) |

Some analysts worry about a return to so-called stagflation, a combination of weak growth and high inflation. Fortunately, Vietnam is well placed to continue its recovery. Foreign direct investors are strongly attracted by the country, in particular its economic stability and abundant labour supply.

The reopening of the borders will bring renewed support to activity and employment, especially in small businesses. The economy will benefit from the fiscal package approved by lawmakers in January, with nearly VND350 trillion ($15.4 billion) earmarked to prop up the country in the 2022-2023 period.

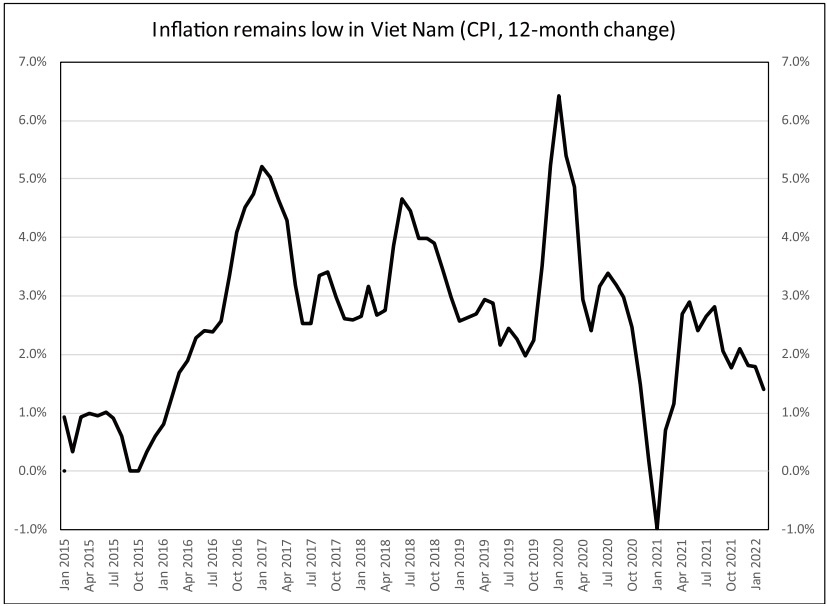

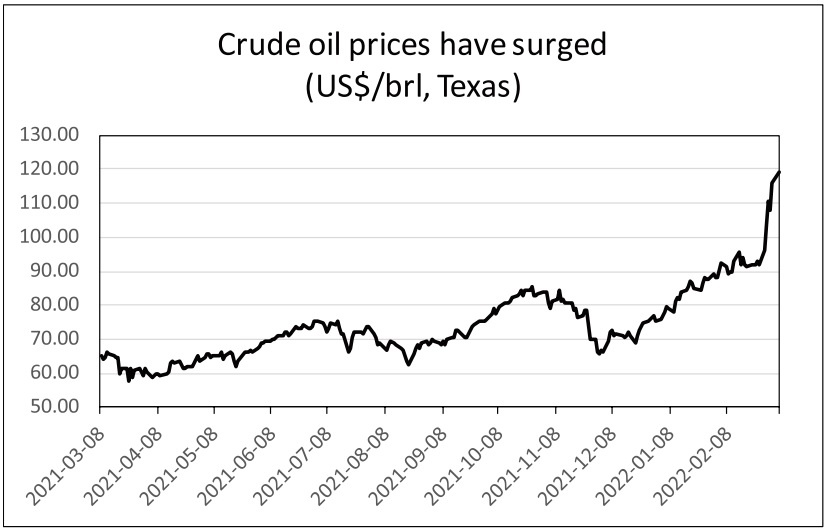

The energy crisis has not spared Vietnamese citizens. Gasoline and diesel prices have jumped several times since early January. Nonetheless, inflation remains low so far – only 1.4 per cent in February. This is well below price increases in the eurozone (5.8 per cent) and the United States (7.9 per cent), where spikes in energy prices have already pushed up inflation rates to the highest levels in 40 years.

Vietnam’s inflation has remained low because the government regulates the prices of many goods and services such as electricity, refined petroleum, transportation, healthcare, and education, and can therefore decide to increase prices at a gradual pace to soften the blow.

Exposed to costs

In addition to regulating prices, the government can cut taxes. For gas, taxes and fees account for 42-43 per cent of retail prices in Vietnam, so there is potential to cut taxes and therefore tame inflation.

Earlier this year, the government decided to reduce VAT by 2 per cent, but refined petroleum products were excluded from this measure.

The government has now proposed to cut by half from April 1 the environmental tax on gasoline and diesel, which would help families who buy these products, although it would deprive the state budget of significant tax revenue.

For most Vietnamese households, energy is expensive: filling up a 40-litre gasoline car tank costs over 20 per cent of the average monthly income, much more than in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, according to the World Bank and others.

Car ownership is still limited in Vietnam, but households are exposed to higher energy costs for their transportation, heating, cooling, cooking, and electricity. In many countries, skyrocketing energy prices entail a risk of energy poverty.

Past energy crises have often been followed by weaker economic growth and high inflation but this is unlikely to happen. Making precise forecasts is impossible given high uncertainties, but major institutions have made modest cuts in their projections of global GDP growth in 2022.

China is a large importer of energy and is likely to expand less rapidly. The US is better protected because it is a large energy producer. Europe is close to the conflict zone and depends on Russian energy, so the European Central Bank has lowered its projections.

Vietnam’s growth prospects remain favourable as it exits from the pandemic and reopens its borders to tourism. The country is also attracting more foreign investment, and factories are operating at high levels. The new fiscal stimulus package adopted by lawmakers for 2022-23 will also support growth, while the VAT rate cut by 2 per cent will lower inflation in the short term.

High energy prices are especially harmful to low-income citizens. Many governments have therefore decided to help them. Policy measures range from cash transfers to low-income people, tax cuts on energy products, energy price controls, and taxing excess profit taxes of energy companies.

In China and the US, state oil reserves have been released to push down prices, and in France and Japan, increases in electricity and natural gas prices have been capped, and cash transfers sent to low-income households. In India, excise duties on gas and diesel have been cut, and so has VAT.

|

|

Thinking of the long-term

Vietnam could follow some of these examples. The decision to cut gas and diesel taxes will benefit the owners of passenger cars, typically well-off citizens. However, cash transfers to low-income consumers would be a better-targeted policy intervention. Smaller businesses struggling to pay energy bills could also be helped with deferrals of taxes and loan repayment.

These intervention prices are useful in the short term, and they will sharply reduce the risks of stagflation in Vietnam, as they will in other countries. But they do not solve long-term problems. Vietnam depends increasingly on imported energy and therefore cannot escape the volatility in global markets. The country produces relatively small quantities of crude oil, natural gas and coal, which are not enough to meet its domestic consumption.

According to Vietnamese customs statistics, energy imports have been on an upward trend, with over $12.6 billion of energy imports in 2019, including nearly $3.8 billion for coal imports. Crude oil is imported in greater volume to meet the needs of Nghi Son oil refinery. More coal is imported to generate electricity. Vietnam is building a liquefied natural gas terminal to enable a greater volume of imports. Depending on imported energy is unavoidable in the short term, but reducing this dependence is essential in the medium term.

Accelerating Vietnam’s green transition would be a win-win strategy: it would make the country less reliant on energy imports, and therefore improve its energy security, and it would contribute to the fight against climate change. Vietnam has already increased its production of renewable energy, notably rooftop solar panels.

More will be needed to improve energy independence and at the same time reduce carbon emissions. Offshore wind power is a huge potential source of clean electricity in Vietnam, which has just started to be tapped.

Last year, Vietnam pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, cut down methane emissions by 30 per cent by 2030, and more besides. However, achieving this faces many hurdles: it will require large-scale investment, new funding, better tech, and a significant reskilling of workers. But this will eventually boost energy security and protect Vietnam from future crises.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- E-vehicle infrastructure financing for high growth (February 20, 2026 | 15:09)

- Green finance and circular economy as drivers of growth (February 18, 2026 | 20:35)

- EVN awards EPC contract for Quang Trach II LNG project (February 10, 2026 | 09:00)

- Canada backs Vietnam’s green transition with AGILE project (February 09, 2026 | 17:41)

- Momentum is real in the race to net-zero emissions (February 02, 2026 | 08:55)

- $100 million initiative launched to protect forests and boost rural incomes (January 30, 2026 | 15:18)

- Trung Nam-Sideros River consortium wins bid for LNG venture (January 30, 2026 | 11:16)

- Vietnam moves towards market-based fuel management with E10 rollout (January 30, 2026 | 11:10)

- Envision Energy, REE Group partner on 128MW wind projects (January 30, 2026 | 10:58)

- Vingroup consults on carbon credits for electric vehicle charging network (January 28, 2026 | 11:04)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version