From aspiration to reality for PDP8

The PDP8 continues to prioritise the development of renewable energy to further Vietnam’s commitment to reach net-zero emission in 2050. By 2030, renewable energy capacity is expected to reach 40GW or 40 per cent of the national power capacity. There will be no limit on the capacity of behind-the grid solar power projects, and no new coal-fired projects are approved. The coal-fired power capacity is targeted for reduction to 20 per cent of national capacity in 2030 (compared to 30 per cent today) and elimination by 2050.

|

| Ngoc Nguyen, counsel at Hogan Lovells International LLP |

At the end of 2021, the wind and solar energy capacity of Vietnam reached 20.6GW, or 27 per cent of national capacity. Doubling the current capacity in the next seven years is well within reach. After new regulation is enacted to realise the removal of the cap on the capacity of behind-the-grid solar power projects, there will be abundant new opportunities for investors who do not need to rely on Electricity of Vietnam (EVN) to offtake energy.

Although wind and solar energy comprises nearly 30 per cent of national capacity, their generation rate has been limited to 10-13 per cent due to the weather-dependent nature of those energy sources, an overloaded grid, and regulatory issues causing delay to projects. A balanced development strategy between small renewable power projects and other more stable energy sources including offshore wind and gas-to-power will be important to address the ongoing supply crunch.

Compared to the first draft in late 2021, the final PDP8 has tripled the capacity allocated to offshore wind power projects to 6GW by 2030 or 4 per cent of the national capacity. This target has driven increased investor confidence in the prospects of offshore wind projects in Vietnam.

The government will need to urgently develop the legal framework for granting site survey licences and selecting investors in offshore wind projects. Perhaps because the policymakers understand those regulatory developments will take time, despite the ambitious 2030 target for offshore wind, the PDP8 includes an initially confusing but ultimately logical provision that the government does not plan to develop major inter-regional transmission lines connecting central southern provinces (where all the major offshore wind power projects being proposed) to the northern region (where electricity demand is highest) before 2030.

Priority for gas-to-power

As coal-fired projects are phased out, development of gas-to-power projects becomes increasingly essential to ensure a stable base load. The PDP8 prioritises domestic gas to reduce the country’s foreign dependence. By 2030, power projects using domestic gas are targeted to have a total capacity of 15GW or 9.9 per cent of national capacity.

At the end of 2020, the total capacity of domestic-gas fired power projects was about 7GW: a result of over two decades’ development. History teaches us that doubling existing capacity to 15GW in seven years will require hard work. No new domestic gas fields have been developed in Vietnam in the last 10 years, and existing production is declining. The two major gas fields, Blue Whale and Block B, declared commercial discoveries more than 10 years ago but have not yet started production.

|

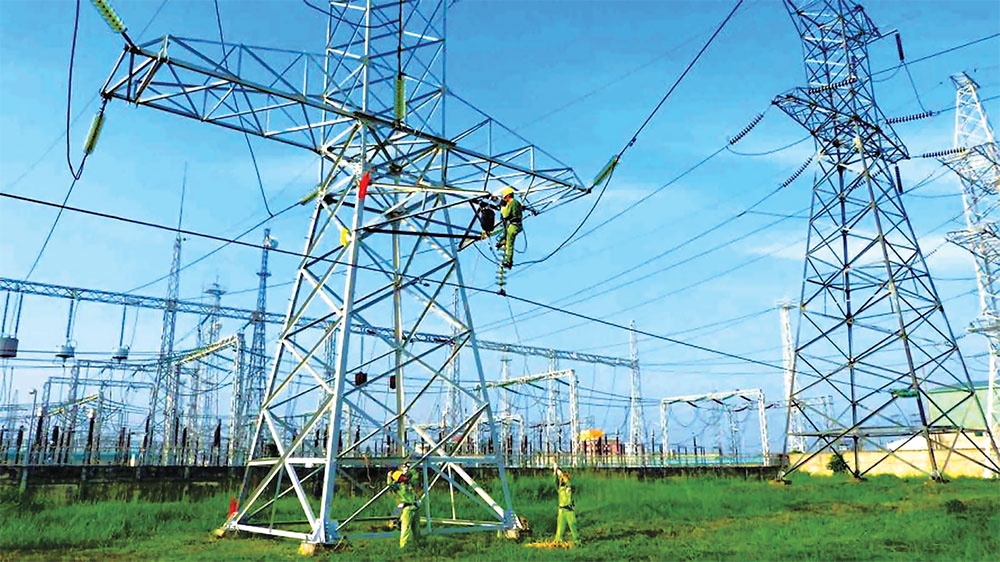

| There will soon be opportunities for investors who do not need to rely on Electricity of Vietnam to offtake energy, photo Le Toan |

Most recently, in May, EVN requested PetroVietnam to prioritise gas supply to power plants at the expense of suspension of two important fertiliser plants in southern Vietnam, a proposal not well received by PetroVietnam and the agriculture industry.

One major bottleneck that has long delayed upstream domestic gas projects is the gas offtake price payable by downstream power plants, most of which are owned by state-owned PVPower and EVN.

To close the gap, a coordinated effort between the gas and power industries will be required, in which the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MoIT) as the regulator of both industries must be empowered (and shielded from liability arising solely for market reasons) to make bold decisions based on a realistic assessment of domestic gas supply capacity and electricity demand.

Perhaps the bravest ambition of the PDP8 is in its plan for liquefied natural gas (LNG) to power. In less than seven years, the LNG-to-power capacity of Vietnam is targeted to grow from zero to 22.4GW, accounting for 14.9 per cent of national capacity. By 2030, LNG-to-power projects are targeted to supply 14.7 per cent of national demand.

The PDP8 includes a list of 15 LNG-to-power projects that will be prioritised before 2030. About one-third of those projects have not been awarded to investors and may be subject to competitive bidding for investor selection, a complex and time-consuming process. Some 14 out of 15 projects have not achieved financial close, let alone commenced construction. It is worth noting that prior thermal power projects in Vietnam took 7-10 years to reach financial close.

Relying on LNG-to-power to supply over 14 per cent of national demand by 2030 could be either a risky bet or a brave decision of the Vietnamese government to phase out coal. If the latter, urgent actions will be required to assist the shortlisted projects to secure financing. A robust power purchase agreement with a well-balanced risk allocation mechanism will be critical.

The PDP8 anticipates the potential delay of LNG-to-power projects by prescribing that if any of those projects are potentially delayed, the prime minister may decide to replace the delayed projects with others. But investors will not invest millions of US dollars to prepare for a project if it is not listed in the plan. A replacement project at an interim stage of development may in reality be nowhere to find when the time comes.

Awareness of capital needs

Vietnam will require about $12 billion of investment annually in 2021-2030 for developing power plants. In 2011-2020, capital expenditure from EVN made up only one-fifth of $75.5 billion investment capital in electricity generation. Private and especially foreign capital will continue to be critical to the growth of the power industry in the next decade. As pointed out in the PDP8, it is important that the government creates better conditions for private investors and lenders investing in Vietnam. In addition to classic financing hurdles, other issues have emerged in recent years.

Uncertainty in the legal framework and its enforcement in the past few years has reinforced investors’ concerns about change-in-law and curtailment risks in Vietnam. If no compromise is offered by the government, the prospect of finding financing for future large scale offshore wind and gas-to-power projects will dim considerably.

Legal restrictions on offshore refinancing have also materially affected the liquidity of projects. Inflexible interpretation of the law by certain government authorities when assessing the financial and technical quality of investors has failed to take into account different corporate structures commonly used in the international market, restricting the ability of certain types of investors to participate.

The requirement that an investor use its ultimate parent company (rather than a special purpose vehicle) to own projects would be commercially unacceptable for most international sponsors.

The conventional assessment of equity capital of the investors based on their balance sheet may unfairly and unreasonably exclude investors structured as private equity funds, starving Vietnam’s power industry of an important source of funding. Rather, the government should take into account the broader capacity of the ultimate investors in those funds and the track records of fund managers and their affiliated funds in developing projects globally.

The success of renewable energy projects in the last five years has contributed significantly to the economic development of Vietnam. There is no doubt that the strong commitments and bold actions taken by the government, especially the MoIT and EVN, were among the most important success factors. Those actions should be appreciated in the context of the nascent legal framework, where the regulators and the market were left with no choice but to learn by doing.

However, growth has its inherent growing pains. If this pain is not managed appropriately, it may dissuade others from proceeding when there is a lack of clarity about the future. Following the PDP8, the market is looking for bolder and stronger actions from the government to push forward those aspirational goals, which cannot be achieved if key stakeholders are intimidated by, or punished for, taking actions required to achieve those goals.

To avoid the current situation in the north spreading further, any policies or political decisions taken during this critical time should take into account their impacts on the power industry with a longer-term view matching the ambition of the PDP8.

| Localities pinning hopes on PDP8 to help beat the heat With clear evidence that Vietnam’s electricity structure is creaking under the current heat and grid overload, the Power Development Plan VIII contains the acute task of successfully implementing an equitable energy transition in association with smart grid construction and advanced power system management in line with a greener outlook. |

| HCMC proposes 6,000MW Can Gio offshore wind power plant in PDP8 Ho Chi Minh City Department of Industry and Trade has put forth a proposal to incorporate the Can Gio offshore wind power plant, boasting a capacity of 6,000MW, into the forthcoming Power Development Plan VIII (PDP8). |

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Trung Nam-Sideros River consortium wins bid for LNG venture (January 30, 2026 | 11:16)

- Vietnam moves towards market-based fuel management with E10 rollout (January 30, 2026 | 11:10)

- Envision Energy, REE Group partner on 128MW wind projects (January 30, 2026 | 10:58)

- Vingroup consults on carbon credits for electric vehicle charging network (January 28, 2026 | 11:04)

- Bac Ai Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant to enter peak construction phase (January 27, 2026 | 08:00)

- ASEAN could scale up sustainable aviation fuel by 2050 (January 24, 2026 | 10:19)

- 64,000 hectares of sea allocated for offshore wind surveys (January 22, 2026 | 20:23)

- EVN secures financing for Quang Trach II LNG power plant (January 17, 2026 | 15:55)

- PC1 teams up with DENZAI on regional wind projects (January 16, 2026 | 21:18)

- Innovation and ESG practices drive green transition in the digital era (January 16, 2026 | 16:51)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version