Will international stress disrupt Vietnam’s economic recovery?

|

| Patrick Lenain-Former assistant director Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

Pressures on global supply chains are also a key headwind in the recovery. Supply chain disruptions are not new: health precautions imposed over the last two years have already caused major bottlenecks. Major shipping hubs such as Los Angeles and Shanghai have operated with reduced capacity, with long waiting times to get shipments processed across the borders.

With the pandemic fading away, congestion in international supply chains has eased a bit since December 2021. In the United States, government agencies have worked with shippers, retailers, and port authorities to speed up the movement of goods.

For instance, ships waiting to unload containers in US ports have declined by 35 per cent, thanks to 24/7 operations and large recruitment of workers. However, the lack of US truck drivers has emerged as a new problem. Action was taken to hire 30,000 additional truck drivers, including apprentices, women and veterans – all with higher salaries.

The problem then became the lack of trucks, as critical components are impeding the assembly of new trucks in factories. Similar problems have been faced around the world.

Though the situation has improved around the world, containers are still moving too slowly.

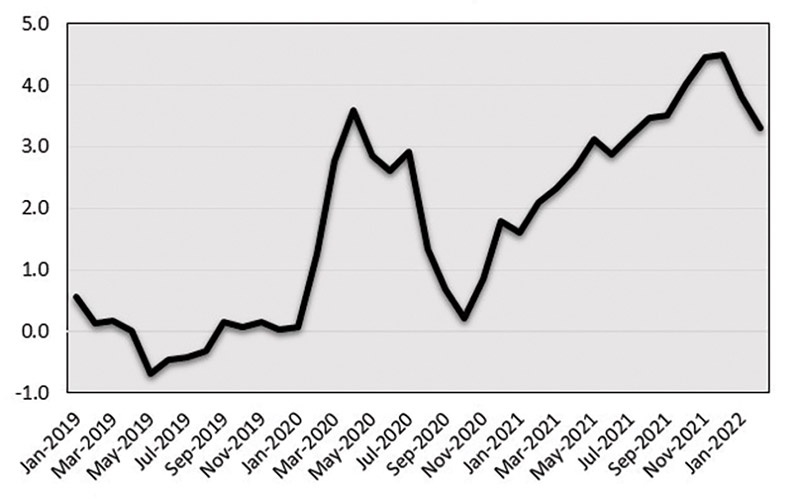

An index compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (see Figure 1) shows that global supply chains remain stressed relative to pre-pandemic levels, and similar indicators put together by ABN-AMRO and the US Department of Transportation reach similar conclusions.

Differing policies

Vietnam’s exports of goods to the United States reached $96.29 billion last year, up 24.9 per cent on-year, so Vietnamese businesses will welcome that the situation is slowly improving in this country. However, the situation has worsened in China – the country’s second-largest foreign market with exports of $56 billion in 2021, up 14.5 per cent on-year. Coronavirus outbreaks in dozens of Chinese cities have prompted the return of strict lockdowns.

Most countries have by now decided to live with COVID-19 and allow the coronavirus to circulate almost freely, but China still adheres to its “zero-COVID” policy. Over 300 million Chinese citizens have been told to remain indoors for more than a month, with strict rules for getting access to daily necessities.

In Shanghai, one of the busiest manufacturing hubs in the world, this has created severe logistical problems. A backlog of ships is waiting to unload cargo. Once unloaded, logistical challenges are getting trucks and drivers to pick up the containers and move them out of the harbour. Drivers need to take frequent COVID-19 tests, face lengthy quarantines, and must obey clearance times to enter Shanghai. Some products require special licensing requirements, such as food items. All these procedures have raised the cost of shipping a container to and from China multiple times – with an impact on business profitability.

Even crossing the China-Vietnam land border has become a challenge faced daily by hundreds of truckers. Chinese authorities have prohibited Vietnamese truck drivers from crossing the frontier, so shipments need to be offloaded, decontaminated, and reloaded on Chinese trucks – all with staff in full protective equipment.

China’s lockdowns will eventually be relaxed. However, clearing up piles of stranded containers will take time, and strict lockdowns may happen again as long as China retains its policy.

Vietnam could draw lessons from other countries and reduce logistical stress. Like in the United States, a task force could be established involving Vietnamese authorities, customs, shippers, businesses, and retailers to agree on practical solutions. Introducing 24/7 operations at the borders, including holidays, will help to process more shipments and clear up logjams. Using digital declarations and online submissions will expedite formalities.

Businesses may not be able to cover the additional costs of these procedures, so government financial support is warranted, as done by the US Department of Transportation’s decision to provide funds amounting to $450 million to ease bottlenecks.

Nonetheless, disruptions will not go away entirely, so businesses should be prepared: stockpiling essential inputs will be preferable to relying on just-time-delivery; exploring new delivery routes with different border crossings will be better than using a single pathway; diversifying the customer base in different countries and provinces will also build resilience in the face of future disruptions.

|

| Stress in global supply chains has declined, but remains elevated |

Conflicts and reopenings

The Russia-Ukraine military conflict is also a threat to global recovery. For Vietnamese businesses, the conflict may seem far away, but it is a direct hit on them. Before the conflict, Russia and Ukraine were large suppliers of various types of energy and grain to global markets. With the availability of Russian and Ukrainian products now much reduced, commodity prices have skyrocketed.

Even though Vietnam is a large producer of energy and food staples, it nonetheless imports large quantities of oil, coal, natural gas, fertilisers, iron, steel, aluminum, and agricultural commodities. For Vietnamese businesses using these items, this means higher input costs, which cannot always be fully passed on to sales prices paid by customers, thus hurting profitability.

The conflict has also disrupted international shipping: military forces have shut off shipping lanes in parts of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. The airspace over Ukraine is now closed to civilian airlines, and the airspace over Russia is avoided by them. This has decreased the capacity of international airfreight carriers, which are required to take alternate, longer routes, pushing up fuel costs. Spiking airfreight rates will be felt by Vietnamese businesses flying products to the region.

Furthermore, Western countries imposed sanctions, with global repercussions. Many of Russia’s commercial banks have been locked out of the SWIFT international payment system, which connects more than 11,000 banks and financial institutions in over 200 countries and territories. This has made it very complicated to make and receive payments from Russia, affecting bilateral trade between the two countries.

Elsewhere, tourism accounted for 9.2 per cent of GDP before the pandemic, but COVID-19 has crushed it to only two per cent. Hopes are high that the reopening of borders will see a fast return of international visitors, but disruptions caused by China’s strict confinement rules and by the Russia-Ukraine conflict will hurt.

Almost six million Chinese tourists were visiting Vietnam annually before the pandemic, the largest foreign group. China’s authorities have banned Chinese travel agents from selling outbound group and package travel since January 2020, and this ban was last reiterated in a press conference in March this year. Restrictions on returning to China are also very tight, including quarantine-on-arrival and health monitoring at home, making international travel impractical.

Over 600,000 Russians were visiting Vietnam annually before the pandemic, another important group. Since late February, Vietnam airlines and Aeroflot have cancelled direct flights between the two countries. In addition, Russian tourists can no longer use their Visa, Mastercard, and American Express cards when travelling abroad. Other options are available, such as Russia’s Mir card, but with limited acceptability.

Despite this, Vietnam’s tourism sector has a bright future. Other touristic hubs previously hit by crises – such as Egypt, France, Greece, Morocco, and Tunisia – were able to rebound. Vietnam’s government can help the travel industry explore new markets and adapt its marketing actions to cater to tourists with different tastes, interests, and languages.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Kurz Vietnam expands Gia Lai factory (February 27, 2026 | 16:37)

- SK Innovation-led consortium wins $2.3 billion LNG project in Nghe An (February 25, 2026 | 07:56)

- THACO opens $70 million manufacturing complex in Danang (February 25, 2026 | 07:54)

- Phu Quoc International Airport expansion approved to meet rising demand (February 24, 2026 | 10:00)

- Bac Giang International Logistics Centre faces land clearance barrier (February 24, 2026 | 08:00)

- Bright prospects abound in European investment (February 19, 2026 | 20:27)

- Internal strengths attest to commitment to progress (February 19, 2026 | 20:13)

- Vietnam, New Zealand seek level-up in ties (February 19, 2026 | 18:06)

- Untapped potential in relations with Indonesia (February 19, 2026 | 17:56)

- German strengths match Vietnamese aspirations (February 19, 2026 | 17:40)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version