Practical investing in PPP stemming from new decree

|

| Tony Foster, managing partner at the Vietnam offices of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP |

In Vietnam, infrastructure covers more than roads and railways. The new Law on Public-Private Partnership Investment, which became effective in January, covers six sectors: transport, power, water, healthcare, education, and IT infrastructure.

Practical implementation of this law is of critical importance to Vietnam. The government has a $120 billion public investment budget for the next five years. That is 35 per cent higher than the previous one and is about one-third of 2020 GDP. To put this in context, that is about $7 trillion on a US scale if adjusted for comparative GDP.

Priority for budget money goes to major projects, such as ring roads, expressways, digital infrastructure, science and technology, and social infrastructure such as hospitals. That leaves a big dependency on official development assistance (ODA), and the private sector, including public-private partnerships (PPPs), for the rest.

But ODA is itself declining as Vietnam becomes a middle-income country. It is still visible in the metro projects, but is not nearly as prevalent as before. So that leaves the private sector to finance the infrastructure for which budget funds are not available. The private sector will do this if the incentives are right (as they were recently for solar power, where feed-in tariffs were generous enough to spark the construction of 18GW of capacity). It will also do it if the protections are right. That is where the PPP regulations are important.

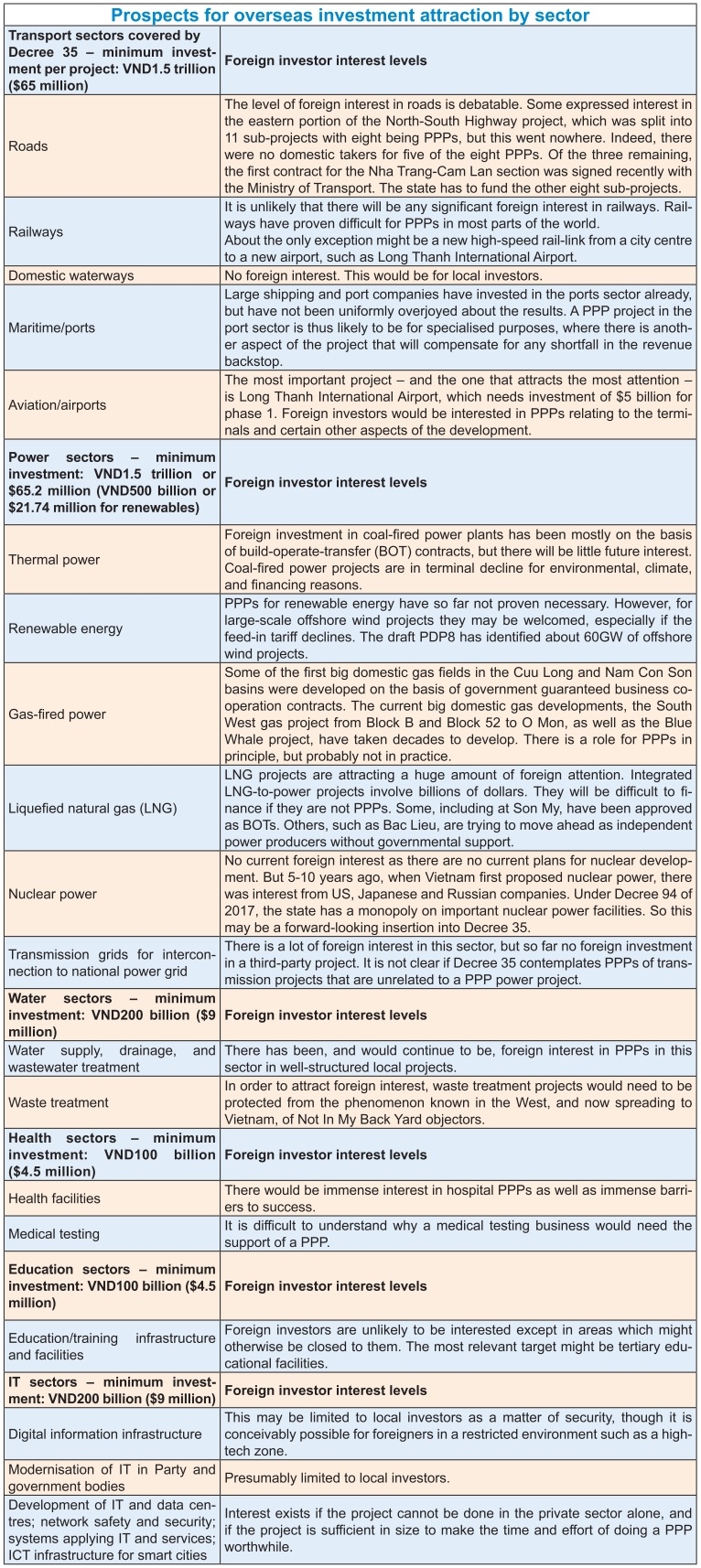

These regulations have a new addition in the form of Decree No.35/2021/ND-CP dated March 29 detailing and guiding the implementation of a number of articles of the Law on Public-Private Partnership Investment. This provides the specificity needed to know if a sector is covered by the law. Foreign investors will provide much needed capital into some of these sectors but by no means all of them.

The levels of foreign investor interest in PPPs will depend on the protections available. This is not because foreign investors do not take risks, but because lenders do not. The lenders could push risks back onto the foreign investors, but when the size of the project is too large for the investor to take such risk, the PPP will not be completed.

Decree 35 does not assist much in this allocation of risk and hence does not assist much in making PPPs more likely to be successfully project financed. One of the main risks in respect of which lenders are cautious is the termination risk. If a project terminates, and it is not as a result of a breach by the developer, lenders want the outstanding amount paid to them by the government. Decree 35 does not state such a principle, or any lesser variation of it. It merely states that the parties can agree on a formula or mechanism for determining the compensation amount. So it is possible to negotiate a satisfactory contractual provision. But, unless there is a clear policy on minimum protections, it is unlikely to be achieved in practice, at least in the immediate future. Developers may not even spend the time and money required to test whether it is possible to negotiate the required protection.

Decree 35 also fails to provide any protection to a developer against a change in law, presumably on the basis that the protections in the Law on Investment are adequate (project finance banks beg to disagree). A change in law can put up the costs for a PPP project, even if the revenue is fixed. This reduces the amount that can be paid back to lenders or that can be retained as profits.

The Law on Public-Private Partnership does have some revenue risk protection in that if revenue from a project falls below 75 per cent of the agreed projections, the state will pay 50 per cent of the difference between actual revenue and 75 per cent of the amount agreed, subject to various conditions. But this alone may not be of sufficient comfort to foreign lenders to large projects.

|

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Tag:

Tag:

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Internal strengths attest to commitment to progress (February 19, 2026 | 20:13)

- Vietnam, New Zealand seek level-up in ties (February 19, 2026 | 18:06)

- Untapped potential in relations with Indonesia (February 19, 2026 | 17:56)

- German strengths match Vietnamese aspirations (February 19, 2026 | 17:40)

- Kim Long Motor and AOJ Suzhou enter strategic partnership (February 16, 2026 | 13:27)

- Haiphong welcomes long-term Euro investment (February 16, 2026 | 11:31)

- VIFC in Ho Chi Minh City officially launches (February 12, 2026 | 09:00)

- Norfund invests $4 million in Vietnam plastics recycling (February 11, 2026 | 11:51)

- Marico buys 75 per cent of Vietnam skincare startup Skinetiq (February 10, 2026 | 14:44)

- SCIC general director meets with Oman Investment Authority (February 10, 2026 | 14:14)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version