PDP8 delay to unlock more cost-effective renewables

The process hit an unexpected delay in late March, however, as the approval process for finalising PDP8 was extended through June, raising important questions about how policymakers will contend with the rapidly-shifting energy sector landscape.

Vietnam remains Southeast Asia’s most attractive energy growth market, with 68GW of new capacity expected to be added to the system between now and 2030 under a base case scenario. So far, there have been three key drivers of this process: a pivot from coal to gas, the growing importance of renewables, and a sea change in funding patterns.

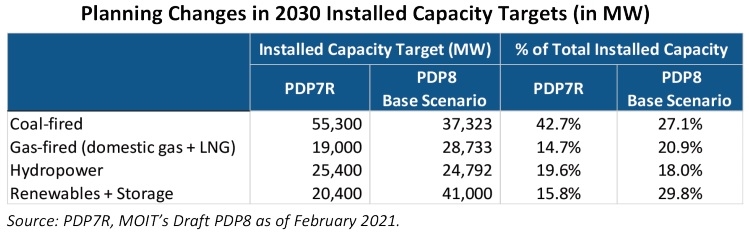

As part of the PDP8 planning process, the country’s top leadership has signaled a pivot away from coal to liquefied natural gas (LNG) for large-scale baseload power. According to the February draft, the 2030 installed capacity target for the coal power fleet was slashed by 18GW compared to the previous power development plan (PDP7). Half of that capacity gap is expected to be filled by additional gas-fired power plants.

There are numerous reasons for this shift, including ongoing setbacks for pipeline coal power projects and rising controversy related to environmental impacts, both at home and abroad. The challenge for power sector planners at the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MoIT) is that the pivot to gas is more closely aligned with the interests of high-profile gas sellers than the very real challenges that Vietnam’s power sector will face if generation mix choices are linked to fixed imported gas offtake obligations.

The high stakes debate about gas is playing out just as the MoIT has begun to reap the benefits of a rapid build-out of renewable power projects over the past two years. The sector was kick-started by successful feed-in tariff programmes that enhance Vietnam’s energy self-sufficiency by tapping into the country’s attractive solar and wind resources.

|

|

Renewables and realities

It is hard to overstate how much Vietnam’s strategic power options have changed as a result. The rapid build-out of rooftop solar capacity in late 2020 has lifted non-hydro renewables penetration to a quarter of Vietnam’s 70GW power system. In the first three months of 2021, despite curtailment, renewable power still contributed to 13.1 per cent of the total system output, up from just 5 per cent in 2020.

With renewables filling critical supply gaps, new system management challenges should be seen as inevitable in the first stages of the clean energy transition pathway, not as a reason to halt progress. If enabled, renewables will continue to deliver on the upside with a new focus on rooftop solar and offshore wind.

Over the past year, global funding flows have shifted as the pool of low-cost capital requiring guarantees for fossil fuel projects began to shrink as governments and investors shun carbon risks. This has been evident in the controversy surrounding the Vung Ang 2 coal power plant project in Central Vietnam, and recent new policy announcements by Japan and South Korea that signal the beginning of a serious move away from coal financing.

In the past decades, the power infrastructure funding challenge was met by lender-centric project finance strategies that were designed to put all the risks on governments that were compelled to offer guaranteed offtake with ratepayers taking all the market risks. Now, new sustainable finance strategies, such as green bond issuance, are beginning to fill the funding gap for renewables players that have been willing to take more market risks in exchange for long-term growth opportunities.

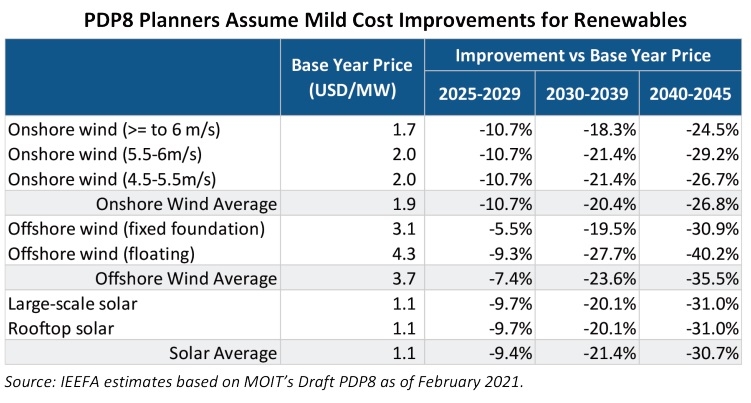

The net effect of these crosscurrents is that Vietnam’s status as the Southeast Asian country on the most positive clean energy trajectory now hangs in the balance as the old economics of LNG are tested against the new economics of renewables. Economists would define this as a price discovery problem.

Simply stated, the MoIT’s challenge is that it is virtually impossible for them to know what the cost of PDP8 will actually be or how its policy choices will affect the willingness of funders to back the developers who are able to win approvals.

In a worst-case scenario, this means that any decisions made now could be derailed over the next three years, resulting in high-profile project delays and sub-optimal decisions on critical system development plans. For a simple demonstration of how fast the scale of technology change can re-order system design priorities, it is instructive to compare the installed capacity targets for 2030 that were set in 2016 under PDP7 versus the scenario envisioned today in PDP8.

The challenge

With implementation risk rising, the government’s decision to delay PDP8 should be applauded. This pause gives senior policymakers a valuable opportunity to stress test the key assumptions that have shaped PDP8 to minimise planning errors. The new power development plan should not lock in imperfect choices when there is an opportunity to design it to expand Vietnam’s options and reject pathways that will lock the country into open-ended price risks.

The key to repositioning PDP8 is to recognise where price discovery risk is the highest and to design market-based mechanisms that will reveal realistic technology cost curves. The planners should also prioritise the market features that matter the most to those developers who have the funding capacity to take market risks. This is critical because the state utility Electricity of Vietnam faces very real funding constraints.

The lack of candid debate about the tariff assumptions emerging from PDP8 could prove particularly risky. While it is probably safe to assume that there will be scope for tariff increases in a post-pandemic recovery, it is crucial to clarify the full life-cycle economics of different technologies and the way that the terms associated with any funding could be a barrier to more competitive market structures.

For example, the MoIT has often pointed to plans for greater reliance on a wholesale power market, but LNG-to-power plants can be a bad fit for a wholesale market if they require guaranteed fuel offtake and fixed capacity payments.

Much of this work on potential market structures has already been tested in other markets, but any work done now should focus on the unique trade-offs that Vietnam may face between LNG and renewables over the next decade. For example, planners would be smart to study the question of whether bundling renewables and storage can cut curtailment risk in ways that will encourage more price competition and unlock cheaper financing by reducing curtailment risk.

A second thorny question that has not been discussed is whether LNG – both the fuel and associated assets – will be repriced if green hydrogen becomes a competitive threat to conventional LNG, changing how LNG is seen in the energy mix. This could also change assumptions about how Vietnam might approach the development offshore wind due to its potential to produce extremely low marginal cost power to produce green hydrogen.

With so many market fundamentals evolving rapidly, Vietnam has a unique opportunity to use this pause to maximum advantage. In addition to focusing on price discovery, a second priority should be placed on investment choices that will expand, rather than restrict, options to integrate new technologies as they are proven in the marketplace. Resilience and “future-proofing” can seem like strategy consultant buzzwords, but in Vietnam’s case these issues will be more important than fine-tuning generation mix assumptions for the post-2030 period.

As many market commentators are now acknowledging, the decisions that emerging markets make about power now will position them for success or failure over the next nine years. That’s why regional energy growth markets with high climate risk exposures like Bangladesh and the Philippines are embracing this lens to avoid lock-in and to prioritise grid investment.

If the MoIT wants to get maximum benefit from this pause, it is time to go back to project fundamentals and market incentives. Many fossil fuel project developers’ aggressive lobbying efforts over the past year have created a chaotic picture. Some of the projects that are claiming priority positioning in PDP8 suffer from project fundamentals that seem to be at odds with the careful work that has been done by policymakers to develop a disciplined public-private partnership legislation and project qualification standards.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Themes: Sustainable Energy

- 16th national conference on nuclear science and technology opens in Danang

- Technology and Energy Forum 2023 to open in Quang Ninh

- Asia Clean Capital Vietnam receives backing from Swiss Investment Manager

- Amazon scales renewable energy to fight climate change

- Universal Alloy Corporation Vietnam partners with Asia Clean Capital Vietnam

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- VNPAY and NAPAS deepen cooperation on digital payments (February 11, 2026 | 18:21)

- Vietnam financial markets on the rise amid tailwinds (February 11, 2026 | 11:41)

- New tax incentives to benefit startups and SMEs (February 09, 2026 | 17:27)

- VIFC launches aviation finance hub to tap regional market growth (February 06, 2026 | 13:27)

- Vietnam records solid FDI performance in January (February 05, 2026 | 17:11)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

- EU and Vietnam elevate relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership (January 29, 2026 | 15:22)

- Vietnam to lead trade growth in ASEAN (January 29, 2026 | 15:08)

- Japanese business outlook in Vietnam turns more optimistic (January 28, 2026 | 09:54)

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version