How to reopen safely after a pandemic

|

| Patrick Lenain, assistant director at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) |

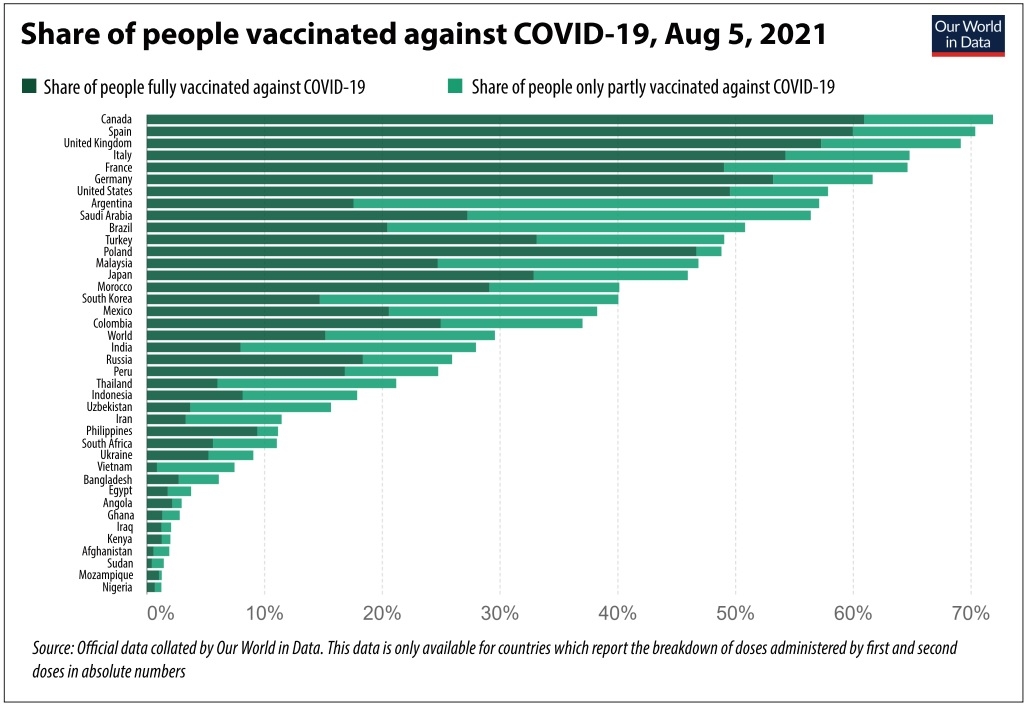

Vaccination is the top priority to stop the pandemic. Four billion doses have already been produced and administered globally and an additional 34 million doses are inoculated each day. Unfortunately, progress is very unequal worldwide.

The US has fully vaccinated half of its population and 40 per cent of Europeans are too. Vaccination works well. Where many people get vaccinated, hospital occupancy decline sharply and COVID-19 mortality falls drastically. With lower circulation of the virus, economic reopening can happen fast: lockdown restrictions are lifted, consumers return to shopping centres and economic activity rebounds. Indeed, in advanced economies, growth is projected to reach almost six per cent this year.

In low-income countries, unfortunately, reopening remains a distant prospect: only 1.1 per cent of their population has received at least one dose in these countries.

In Vietnam, vaccination has made impressive progress, but only 7 per cent of the population has received at least one injection, according to Our World in Data – not enough to control the outbreak. Advanced countries were quick to order huge quantities of vaccines and pay for them. For developing economies, the high cost of vaccines has been a serious obstacle.

Where vaccine supplies are tight, the spread of the virulent Delta variant is having devastating effects. Intensive care units are once again congested, and more lives are being lost. Vietnam’s biggest cities had to impose new restrictions to curb the infection. Some states in India had no other choice than to impose new lockdowns, while Thailand’s reopening plans are cast into doubt. Difficult to fully reopen the economy when this happens. Accelerating vaccination is, therefore, an utmost priority.

As often stated by health officials, the pandemic is not over anywhere until it is over everywhere. Until then, new clusters could emerge and highly contagious mutations could derail ongoing efforts. Most low-income countries need urgent support from the international community to procure large quantities of vaccines: initiatives such as collective vaccine procurement vehicles COVAX, the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust, and bilateral donations of surplus vaccine doses play a key role.

Vietnam has received over 14 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines from multiple sources including bilateral donations, COVAX, and its own procurement. A big boost in supply, but more will be needed to fully vaccinate the country’s large adult population.

Improving vaccine distribution

Now is the time for the world to produce vaccine doses in record quantities. At the current pace of production, about six billion doses will have been made available by the end of 2021. This is great, but not enough to protect the entire world population, especially if “booster shots” (a third injection) are required for long-lasting protection.

If large-scale support is given by the international community to ramp up production, there will be enough doses available next year to vaccinate 60 per cent of the global population by mid-2022 – putting the entire world on a path towards reopening.

But producing many doses of vaccine is not enough: sometimes vaccines remain unused on airport tarmacs beyond their expiration dates due to difficulties in distribution. Logistical challenges are huge to bring vaccines where they are needed – not least, freezers to store doses at ultra-low temperature. While there are many vaccination centres in large cities and affluent neighbourhoods, reaching people in rural and poor neighbourhoods is a different story.

Reaching out to the unvaccinated is crucial. Vietnam can learn from other countries’ experience: registration procedures should be easy, including for those who do not have access to digital tools; free transportation should be provided to vaccination centres for the sick and elderly, door-to-door visits should be organised to provide information, mobile vaccination clinics should reach people in remote areas, and temporary vaccination sites should be established in shopping centres and street markets.

Vaccine hesitancy needs also to be addressed. Only 70 per cent of people agree to be inoculated in advanced countries. In India, Japan, and Russia, willingness to be inoculated is even lower. Because of hesitancy, vaccination campaigns often slow considerably when half of the population is inoculated.

In Vietnam, concerns about vaccine safety have emerged following secondary effects, such as blood clots caused by injections of adenovirus-based vaccines, but such deaths are extremely rare.

Misinformation spread by social networks can confuse people and result in losses of lives. Public information campaigns should seek to inform and reassure the public about the genuine risks levels and the effectiveness of existing vaccines.

|

Vaccination passports

Proof of full vaccination is becoming the main tool to reopen safely in some countries. While Vietnam is considering easier rules for overseas travellers with a vaccination passport, it has not yet considered it for domestic residents.

In France, a vaccination passport will soon be required to eat a meal in a restaurant, have a drink in a bar, exercise in a gym, visit a large shopping centre, and travel inside the country by train or plane.

For those vaccinated, restrictions will be largely lifted, while the unvaccinated will face a variety of ongoing restrictions. Greater freedom provided by these passports has already triggered a rush to vaccination centres.

For another French example, healthcare workers in hospitals, clinics, and hospices will also have to be vaccinated or frequently tested, otherwise their work contract will be suspended.

Inspired by France, the United States is now considering a vaccination mandate for federal employees, and similar mandates are being introduced for government employees in New York and California. While these mandates have irked some groups, they are generally well accepted in public opinion, especially when it comes to employees who are in daily contact with the public and thus risk spreading the virus.

These strategies to reopen safely make it possible to envisage normal lives even as the virus circulates. Just like the flu, common cold, and HIV, we might never be able to eradicate COVID-19 entirely. We have to learn to live with the virus.

Strategies of “zero tolerance” adopted in Australia, China, and New Zealand are thus increasingly on the edge. These countries aimed at suppressing the virus behind closed international borders. As soon as new cases emerged, drastic restrictions were imposed: city lockdowns, mass testing, contract tracing, and strict quarantines.

While successful in the short term, no country can remain forever sealed off from the rest of the world. At some point, borders will need to reopen to tourists, business travellers, and students. In the absence of adequate measures, like in other countries, this will lead to new infection waves. Zero tolerance may not be sustainable for a long time.

We need to reopen our workplaces, schools, restaurants, hotels and concert halls – all essential to normal lives.

Reopening safely is possible with vaccination campaigns, sanitary precautions, accurate information, and vaccine passports. Importantly, the international community must help poorer countries achieve high vaccination rates as soon as possible. And we must help our citizens get vaccinated when they live in remote places and struggle in poverty. Vietnam can benefit from such measures. If done right, safe reopening will no longer be a distant hope.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- NAB Innovation Centre underscores Vietnam’s appeal for tech investment (January 30, 2026 | 11:16)

- Vietnam moves towards market-based fuel management with E10 rollout (January 30, 2026 | 11:10)

- Vietnam startup funding enters a period of capital reset (January 30, 2026 | 11:06)

- Vietnam strengthens public debt management with World Bank and IMF (January 30, 2026 | 11:00)

- PM inspects APEC 2027 project progress in An Giang province (January 29, 2026 | 09:00)

- Vietnam among the world’s top 15 trading nations (January 28, 2026 | 17:12)

- Vietnam accelerates preparations for arbitration centre linked to new financial hub (January 28, 2026 | 17:09)

- Vietnam's IPO market on recovery trajectory (January 28, 2026 | 17:04)

- Digital economy takes centre stage in Vietnam’s new growth model (January 28, 2026 | 11:43)

- EU Council president to visit Vietnam amid partnership upgrade (January 28, 2026 | 11:00)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version