Census surmises main population dynamics

|

| Urbanisation is forecast to keep up the pressure on housing developments, especially in Vietnam’s big cities |

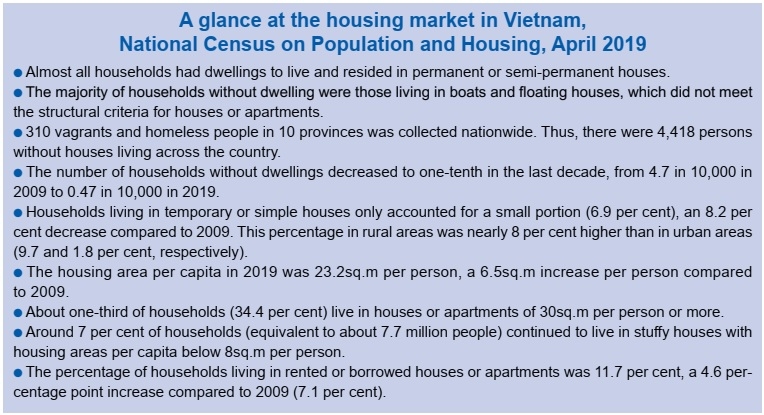

According to the National Population and Housing Census 2019, Vietnam’s population has exceeded 96.2 million people, making it the third-most populous country in Southeast Asia after Indonesia and the Philippines and the 15th most populous country in the world. The proportion of the urban population increased from 20.1 per cent in 1989 to 34.4 per cent in 2019.

Vietnam is witnessing strong urbanisation in big cities, especially in the two largest and most vibrant cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, as well as key economic zones.

The urban population was more than 33 million, or 34.4 per cent of the total population, while the rest (65.6 per cent) resided in rural areas. The average annual population growth rate in urban areas between 2009 and 2019 was 2.64 per cent, more than twice the average annual population growth and nearly six times the figure in rural areas over the same period.

According to Tran Ngoc Chinh, chairman of the Vietnam Association for Urban Planning and Development, by 2020, 40 per cent of the Vietnamese population will live in cities, with population density putting immense pressure on urban housing development.

“With the average population growth of 2-3.4 per cent in urban areas every year, the demand is also increasing fast,” Chinh said.

Although the population has been continuously increasing, migration has decreased in both quantity and proportion, which means urbanisation is slowing down as well.

Migrants tend to choose destinations within a familiar range. Among the 88.4 million people in Vietnam aged five and older, migrants numbered 6.4 million (7.3 per cent), according to the 2019 census.

Southeast Vietnam was the most attractive destination for migrants, followed by the Red River Delta. There were 1.3 million migrants to the southeast, accounting for two-thirds of all migrants in the country.

Twelve provinces had positive net migration rates, with more migrants arriving than leaving. The provinces and cities with high net migration rates include Binh Duong, Bac Ninh, Ho Chi Minh City, and Danang.

Figures from the census show that about 43 per cent of migrants lived in rented or borrowed houses, nearly eight times higher than non-migrants.

Localities with many industrial parks – such as Bac Ninh, Binh Duong, Dong Nai, and Can Tho – that draw unskilled labourers had high proportions of migrants renting or borrowing houses. Other localities that had a relatively high proportion of the migrant population (40-50 per cent) renting or borrowing houses include Thai Nguyen, Hung Yen, Tay Ninh, Ba Ria-Vung Tau, Ho Chi Minh City, and Long An.

|

Increasing demand for housing

The natural population increase and migration from rural to urban areas have created increasing demand for accommodation in the major cities of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

Vietnam sees sharply growing demand for housing in leading urban areas, with the supply shortage predicted to last in the medium term of 2020-2022. In 2018, the average housing space was 24 square metres per person, up 0.6 per cent compared to 2017. In 2019, this figure was 24.5sq.m.

The Ministry of Construction’s statistics showed that around 1.7 million people are in need of homes in urban areas, together with 1.7 million workers demanding stable accommodation, requiring the development of nearly one million sq.m of housing.

It is estimated that in the next 10 years, total new housing demand may reach 5.1 million units in the low- and medium-price segment.

Moreover, Chinh said, the scale of families in Vietnam has been getting smaller. Vietnam has more than 25.5 million of households. About 65 per cent of those are from two- to four-person families, a group that has been showing increasing demand for accommodation.

Troy Griffiths, deputy managing director of Savills Vietnam, said that Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi are currently undergoing a rapid transformation to catch up with regional neighbours.

“Ho Chi Minh City’s apartment market is shored up by strong occupier demand, whilst the high-end segment is appealing to both local high-net-worth individuals as well as international purchasers. High levels of capital inflow, increasing numbers of foreign developers, and suitable policies will continue this pattern of growth,” Griffiths said.

He added that local authorities in Ho Chi Minh City have announced a limit on project development in its housing strategy. This has also made the affordable and mid-end residential segment become thirstier. “Complicated and lengthy legal procedures in Vietnam can be a barrier for overseas developers. However, their presence has increased over the last two years and is expected to continue. This increase will bring higher international standards and leverage competitive supply within the market,” he added.

According to Savills Vietnam, historical supply in the country’s cities has been predominantly C-grade dwellings and future supply. Handovers and launches will also be mostly C-grade. This is driven by owner-occupiers who in Vietnam are not overly exposed to debt, so the chance of a housing bubble is low.

Jumping on the bandwagon

One of the waves to drive the Vietnamese real estate market would be the increasing demand for affordable housing by the average- and lower-income earners. Due to this fact, real estate developers are actively focusing investment on the mid-end and affordable segments.

Oliver Brazier, managing director of BRG Capital Investment Management - one of the few foreign investors who have invested in affordable housing in Vietnam – told VIR that there is huge demand for affordable housing right now, due to the increasing population.

With an Affordable Housing Fund established in 2014 in Luxemburg, BRG Capital Investment Management has been developing affordable residential projects in Vietnam, such as the HausNeo, HausBelo, and HausNima in Ho Chi Minh City.

“We started in Vietnam with affordable housing because we thought it was a very interesting market segment. It’s good for Vietnam, especially young Vietnamese people. However, it is becoming a bit more difficult to do affordable housing with the land prices rising, but it is a sign of Vietnam developing,” said Brazier. “We would like to do more affordable housing in Vietnam. Overall, our fund will deliver around 3,500 apartments, which is quite a big figure.”

In 2018, Viet Hung Urban Development and Investment JSC woke up the market by announcing that more than 2,000 units of its Aqua Bay sub-project in Ecopark City in Hanoi – in the proximity of Hung Yen province – sold out a single month after it launched. Units in this project started at around VND800 million ($34,800) per unit.

A range of domestic developers have been building mid-end and affordable houses to offer thousands of products to the market, including Viet Hung Urban Development and Investment JSC, Nha Mo, and Nam Long.

Other developers like Him Lam, Phat Dat, and FLC Group – who have previously concentrated on the high-end segment – are now steering their projects toward the affordable segment.

Meanwhile, foreign investors are jumping on the bandwagon, including South Korean developers N.H.O and Japanese companies like The Global Group, Hankyu Realty, Nishi-Nippon Railroad, and Creed Group.

According to figures from CBRE Vietnam, for the whole year of 2019, the mid-end segment accounted for 69 per cent of total new launches in Ho Chi Minh City and 80 per cent in Hanoi.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Construction estimated that from this year onwards, 70-80 per cent of the housing demand will be in the mid-range and affordable segments.

Currently, the average selling price of mid-end and affordable apartments in the market is VND25-40 million per sq.m ($1,090-1,740), which translates to roughly VND1 to 2.8 billion ($43,500-121,740) for one- to two-bedroom apartments.

The affordable segment saw the strongest decrease in supply in the market. It is exerting huge pressure on customers who have a demand for accommodation.

The main reason for the short supply, as per the statistics, was the increase in land prices and initial costs, which caused investors to prime their products towards higher segments in order to improve profit margins and ensure investment efficiency.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Construction firms poised for growth on public investment and capital market support (February 11, 2026 | 11:38)

- Mitsubishi acquires Thuan An 1 residential development from PDR (February 09, 2026 | 08:00)

- Frasers Property and GELEX Infrastructure propose new joint venture (February 07, 2026 | 15:00)

- Sun Group led consortium selected as investor for new urban area (February 06, 2026 | 15:20)

- Vietnam breaks into Top 10 countries and regions for LEED outside the US (February 05, 2026 | 17:56)

- Fairmont opens first Vietnam property in Hanoi (February 04, 2026 | 16:09)

- Real estate investment trusts pivotal for long-term success (February 02, 2026 | 11:09)

- Dong Nai experiences shifting expectations and new industrial cycle (January 28, 2026 | 09:00)

- An Phat 5 Industrial Park targets ESG-driven investors in Hai Phong (January 26, 2026 | 08:30)

- Decree opens incentives for green urban development (January 24, 2026 | 11:18)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version