Rallying cry for Vietnam’s steadfast net-zero strategy

|

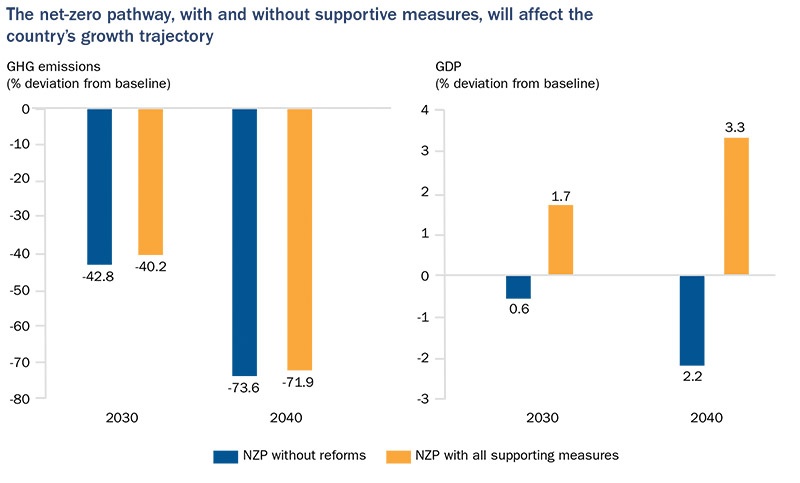

| Source: World Bank |

The World Bank Group last week revealed “shocking” estimations about the grave consequences caused by climate change, and the gigantic losses are expected to be far greater in the future if no proper action is taken to tackle the challenges.

Under fresh assessment in the group’s Vietnam Country Climate and Development Report released last week, Vietnam, transformed in a generation from one of the world’s poorest nations into a dynamic emerging market, faces growing risks that could endanger its goal of becoming a high-income economy by 2045.

The country’s rapid economic growth, urbanisation, and industrialisation have been powered by coal-dependent energy that creates significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Vietnam is not a major emitter of GHGs globally, with 0.8 per cent of the world’s emissions. But over the past two decades, the nation has emerged as one of the fastest-growing per capita GHG emitters in the world.

From 2000 to 2015, as GDP per capita increased from $390 to $2,000, CO2 emissions nearly quadrupled. Moreover, Vietnam’s GHG emissions are associated with the toxic air pollution that plagues many of its cities, especially Hanoi, with implications for human health and labour productivity.

“Hanoi has become among 10 most polluted capitals in the world, partly the result of Vietnam’s economic success. Air pollution causes an estimated 60,000 deaths a year in cities here,” said Muthukumara Mani, lead environmental economist at the World Bank. “Around 300 of Vietnam’s coastal towns are also at risk of flooding, threatening manufacturing and competitiveness. Furthermore, the country’s position as the world’s third-largest rice exporter is also under threat.”

The World Bank report added, “Without rapid adaptation and disaster risk reduction, Vietnam will pay a high cost in terms of damage to the economy and harm to most-vulnerable populations. The vulnerability of poor communities could result in up to one million more people living in extreme poverty by 2030.”

Under the bank’s research, two forecasting models indicate that if nothing is done, total economic losses associated with the change in climate could reach 12-14.5 per cent of GDP annually by 2050, putting huge burdens on both public and private finances. The damage will vary across regions.

Specifically, in the north, rising temperatures are likely to trigger productivity losses caused by heat stress and shorter plant growth cycles, with severe water shortages curbing annual yields. In the central region, coastal areas and cities will be increasingly exposed to flooding from typhoons and tropical storms.

And in the south, the vast Mekong Delta region is particularly at risk from rising sea levels. Almost half of the delta could be inundated if sea levels climb by 75–100cm above 1980–1999 averages, threatening economic losses from increased salinity and rendering the production of some crops impossible.

The region currently creates one-third of Vietnam’s agricultural GDP, half of the country’s rice production, 90 per cent of exported rice, 65 per cent of aquaculture production, 60 per cent of exported fish, and 70 per cent of fruit production.

“Rising emissions will also affect two key drivers of Vietnam’s economy: rice production and manufacturing exports. The high carbon footprint of these two sectors will reduce their competitiveness in international markets,” said Jacques Morisset, lead economist and programme leader at the World Bank in Vietnam.

Huge financing needs

Last November at COP26, Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh impressed the international community with Vietnam’s strong commitment to hit net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, based on the country’s own domestic resources and with the international community’s support.

According to the World Bank, to ensure sufficient funding for responding to climate change, mobilising domestic finance is possible but external support will be needed.

Overall, Vietnam’s total incremental financing needs for the resilient and decarbonising pathways could reach $368 billion over 2022-2040, or approximately 6.8 per cent of GDP per year. The resilient pathway alone will account for 4.7 per cent of this amount as substantial financing will be required to protect the country’s assets and infrastructure as well as vulnerable people.

The cost of the decarbonising pathway will be worth 2.1 per cent of this amount, mainly coming from the energy sector – investments in renewables and managing the transition away from coal might cost around $64 billion between 2022 and 2040. All the figures are in net present value terms at a discount rate of 6 per cent.

This $368 billion in financing needs will include $184 billion from private investments or about 3.4 per cent of GDP annually, $130 billion or about 2.4 per cent of GDP annually from the state budget; and $54 billion or about 1 per cent of GDP per year from external sources.

“Satisfying the funding gap associated with implementing the resilient and decarbonising pathways will require a reallocation of domestic private savings toward climate-related projects, an increase in public savings, and external financial support,” said Mani of the World Bank.

“Aggressive efforts could help mobilise private financing in the range of 3.4 per cent of GDP per year. This can be achieved by mobilising green credit by banks, developing market-based instruments such as green equities and green bonds, and applying de-risking tools. Green finance is in its infancy in Vietnam, and public policy has an important role in helping banks overcome internal and external bottlenecks through regulatory reforms and incentives to both credit providers and borrowers.”

New strategy

Under the support of the international community, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MoNRE) is now drafting Vietnam’s National Climate Change Strategy to 2050. According to a draft decision by the prime minister on approving the draft strategy, by 2030, the total GHG emissions shall decrease by 43.1 per cent compared to the business-as-usual scenario, in which there will be a 32.7 per cent reduction in the energy sector with emissions amount not exceeding 460 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. In the agricultural sector, there will be a decrease of 43 per cent, with emission amount not surpassing 63.9 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. In the industrial processes sector, there will be a cut of 38.3 per cent, with emissions amount not surpassing 86.5 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

“To mobilise financial resources for climate change response (CCR), the government will review, amend, and supplement mechanisms and policies to create favourable conditions and attract international investment capital flows to CCR,” said the draft decision.

Especially, the government will formulate and apply investment incentives to attract private investments into CCR. “It will review, amend, and supplement mechanisms and policies to remove obstacles in procedures, creating favourable conditions to attract investment and green financial flows of financial institutions and international credit institutions to Vietnam, luring international corporations, and multinational corporations to the country to cooperate and implement projects, especially projects on energy production and consumption transformation,” the draft decision read.

The state will prioritise the use of concessional loans, official development assistance, and technical assistance from other countries, international organisations, and non-governmental organisations in CCR.

In the new strategy, Vietnam will continue “develop small hydro-power plants that meet environmental protection standards and expand the number of medium and large hydropower plants. It will also increase the capacity of concentrated solar power plants, rooftop solar power, onshore and offshore wind power, biomass power, and developing technologies for hydrogen, ammonia, tidal, and wave energy,” said Pham Van Tan, vice director of the MoNRE’s Department of Climate Change.

“Vietnam will also gradually shift from coal power to cleaner energy, while reducing the proportion of fossil fuels. Moreover, the country may consider developing nuclear power plants after 2035 when conditions on advanced technology and safety are met,” Tan said.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- VNPAY and NAPAS deepen cooperation on digital payments (February 11, 2026 | 18:21)

- Vietnam financial markets on the rise amid tailwinds (February 11, 2026 | 11:41)

- New tax incentives to benefit startups and SMEs (February 09, 2026 | 17:27)

- VIFC launches aviation finance hub to tap regional market growth (February 06, 2026 | 13:27)

- Vietnam records solid FDI performance in January (February 05, 2026 | 17:11)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

- EU and Vietnam elevate relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership (January 29, 2026 | 15:22)

- Vietnam to lead trade growth in ASEAN (January 29, 2026 | 15:08)

- Japanese business outlook in Vietnam turns more optimistic (January 28, 2026 | 09:54)

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version