Narrowing the gap for PPPs in health

|

| Le Minh Sang, health specialist at World Bank Vietnam |

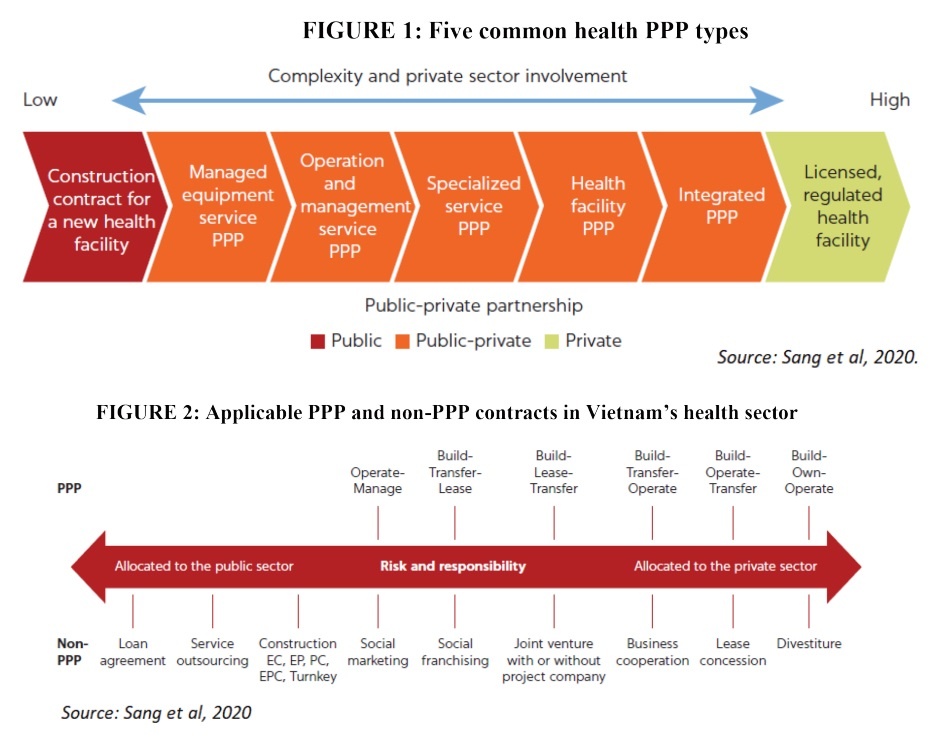

Healthcare public-private partnerships (PPPs) can be classified into five types (see Figure 1) depending on the roles and responsibilities that the private sector takes. Each type has certain advantages and disadvantages. A managed equipment service PPP enables major equipment suppliers to own and manage all equipment required for health facility operations. Under an operation and management services PPP, a private partner is contracted to operate and manage a hospital, health facility, or health network in exchange for a management fee.

Specialised services PPPs involve a government contract with a private partner to deliver specific services (dialysis, radiotherapy, laboratory testing) at public healthcare facilities. In a health facility PPP, the government retains control of clinical services, but the private sector provides some combination of the detailed design, construction, and refurbishment of infrastructure. And integrated PPPs involve a private partner to design, build, finance, and operate facilities as well as deliver nonclinical and clinical services.

In the early 1990s, the Vietnamese government embarked on initiatives to encourage the mobilisation of all possible resources in society towards key public services. Under the healthcare policy, PPPs are among the many contracting tools that the public sector can use to mobilise private finance for the provision of health infrastructure and services.

At least 24 contract types are applicable in the health sector, all of which are regulated in various legal documents. Only contracts specified in the Law on Public-Private Partnership Investment are legally considered to be PPPs (see Figure 2). The remaining contract types are not regarded as such, regardless of the extent to which the private sector shares responsibilities and risks.

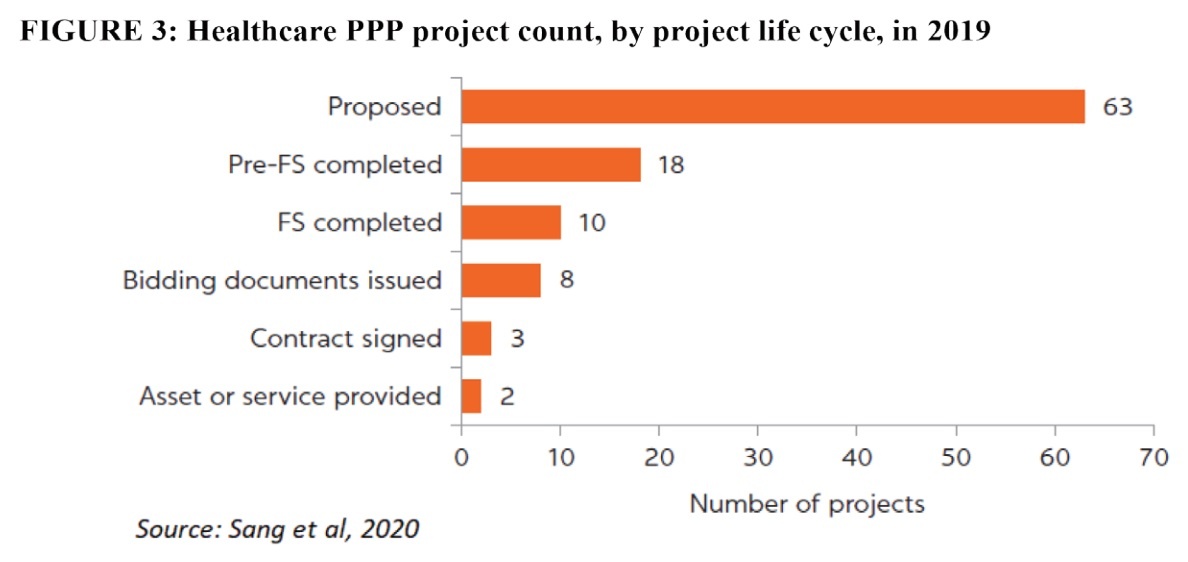

The adoption of healthcare PPPs in Vietnam is still limited. A study conducted by the World Bank in 2019 found a long wish list of 63 projects in the health project pipeline. This high number is indicative of ineffective PPP project screening criteria rather than high potential, and only a small percentage of these projects are expected to reach implementation.

|

Passing the test

Most health PPP projects are proposed and developed at the subnational level. They focus on hospital infrastructure and services rather than on preventive and primary healthcare and are oriented toward higher-income groups in urban areas rather than the disadvantaged groups in rural areas. The proposed health PPP pipeline, therefore, raises questions about equity and efficiency in public sector health service delivery.

The project preparation and approval processes are prolonged, and good governance practices are lacking. By the end of 2019, only 18 projects have completed pre-feasibility studies and 10 projects have completed feasibility studies (see Figure 3). The procurement process for selecting a private partner is ineffective and not sufficiently competitive or transparent. Out of eight projects under procurement, four projects awarded contracts directly to the investors who proposed them, and three applied competitive bidding but only one passed prequalification.

|

Achievements in the actual implementation of healthcare infrastructure and service delivery PPPs are similarly modest. Out of three signed health PPP contracts, a build-operate-own (BOO) contract for the development of a general hospital was terminated due to disagreement among the medical staff and protracted issues with the legal procedure for transferring public assets (land) to the project company.

Elsewhere, a build-operate-transfer (BOT) contract for the development of an on-demand hospital has been problematic for several years because project revenue was far below initial projections and disputes arose over profit sharing; and a build-transfer contract (which was no longer considered as a PPP by the law) for the construction of a public health school has not been completed.

The current framework in Vietnam is not well-fitted with healthcare PPPs. The overall framework is oriented toward infrastructure-type PPPs, downplaying the role of the service-type. It does not support the transfer of service delivery responsibility to the private sector and performance-based payments, which are critical features of a contract. Technical guidelines for screening, designing and, developing related projects remain insufficient.

Furthermore, PPPs have not been embedded in health policies and related health regulations, hampering the use of PPPs to expand infrastructure and improve services in the health sector. Joint ventures between private and public players, in contrast, are legally well established and this framework allows public hospitals to work with the private sector on fast-track arrangements. Stakeholders have far greater motivation and incentives to engage in healthcare projects using the joint venture type model rather than to go the PPP route.

The public sector lacks the institutional capacity to manage complex health PPP contracts. The Ministry of Planning and Investment and big cities have established units, but none has set up a health task force. The team in charge of health PPPs in the Ministry of Health (MoH) consists of three employees, who are not allocated full time to PPP work and are inexperienced in health PPPs. Public health managers at all levels lack the competencies to manage projects and are underfinanced and underinformed to undertake the different steps required throughout the project cycle.

The private sector has strengths in infrastructure development but faces a shortage of highly skilled clinicians. As a result, most public-private engagements in the health sector in Vietnam have had to rely on the recruitment of public sector providers to staff these facilities. Also, the large private healthcare chains, which possess significant resources and operational experience, have shown only tepid interest in partnering with the government in PPPs. In the absence of government financial support for PPP projects, the private sector will recover costs and generate income fully or partially from patients’ or households’ out-of-pocket payments.

The way forward

In the current context, healthcare PPP models and contracts should be adopted with caution. The “asset-heavy, service-light” models, such as equipment and facility PPPs, seem to be the most feasible options. Small-scale “asset-light, service-heavy” models, such as specialised services and integrated PPPs at primary healthcare level, may be suitable for selected projects for which the private sector has a competitive advantage.

Vietnam, however, does not yet seem to be ready for a fully integrated hospital PPP model. Three of the regulated contract types – build-lease-transfer, build-transfer-lease, and BOT – are feasible in the health sector. BOO contracts are not recommended, given the fact that neither the public nor the private sector is prepared for such a full transfer of responsibilities and risks.

In the long term, the government of Vietnam should reorient health PPPs toward equity and efficiency, two objectives of the national health system to ensure that they are suited to the universal health coverage goals and provide value for money under this modality. The institutional arrangements for managing PPPs in should be reinforced by establishing a dedicated unit within the MoH. Public health managers should be trained to augment their capacity and healthcare PPP contracts should also be monitored by key performance indicators, while private partners should be remunerated based on their performance.

| On May 18, VIR will organise a health seminar themed “Strengthening public-private partnerships: Promoting sustainable development of the health sector” to assess existing performance and lessons learned, as well as analyse opportunities to promote health public-private partnerships. With the participation of many leaders of ministries, international organisations, and domestic and international medical/pharmaceutical firms, the seminar is expected to be a useful dialogue between state agencies and the business community, connecting business and investment opportunities between domestic and international enterprises in the sectors of health and pharmaceuticals. The hybrid event will also be livestreamed on VIR’s website and fanpage. Time: 8:00am-12:00pm, Wednesday, May 18. Venue: VIR headquarters, 47 Quan Thanh, Ba Dinh district, Hanoi. |

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Citi economists project robust Vietnam economic growth in 2026 (February 14, 2026 | 18:00)

- Sustaining high growth must be balanced in stable manner (February 14, 2026 | 09:00)

- From 5G to 6G: how AI is shaping Vietnam’s path to digital leadership (February 13, 2026 | 10:59)

- Cooperation must align with Vietnam’s long-term ambitions (February 13, 2026 | 09:00)

- Need-to-know aspects ahead of AI law (February 13, 2026 | 08:00)

- Legalities to early operations for Vietnam’s IFC (February 11, 2026 | 12:17)

- Foreign-language trademarks gain traction in Vietnam (February 06, 2026 | 09:26)

- Offshore structuring and the Singapore holding route (February 02, 2026 | 10:39)

- Vietnam enters new development era: Russian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 10:08)

- 14th National Party Congress marks new era, expands Vietnam’s global role: Australian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 09:54)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version