Measures thrashed out to protect sugar farmers

|

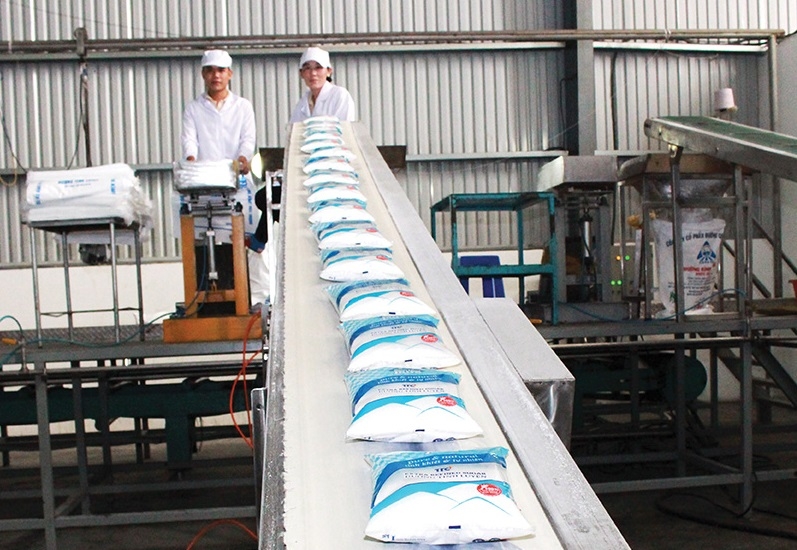

| Domestic sugar mills have been suffering from woes amid regional competition and are in dire need of support |

At this time of the year, Dao Van Duong’s family should be preparing a new crop. However, this year is different as the sudden spike in imported sugar overshadowed even large domestic plantations, like the 15 hectares that Duong and his family are cultivating in Tho Lam commune in the north-central province of Thanh Hoa’s Tho Xuan district.

“The price of sugarcane in the local market is so low, I can only cover the cost for input materials,” Duong said. During the last season, his family and more than 200 other contractors could sell raw sugarcane to Lam Son Sugar Joint Stock Corporation (Lasuco JSC) in the same district for around VND750,000-850,000 ($33-37) per tonne. Now, as each hectare yields only around 60-70 tonnes, Duong is worried that he may lose money in the next season if production costs continue to increase.

In addition to these rising production costs, sugarcane-producing families like Duong’s must cope with competition from abroad. Since January 1, when the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) came into force, Vietnam abolished import quotas for sugar from ASEAN member states, leading to a dramatic increase in imported sugar. In the first eight months of the year, the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MoIT) registered nearly 950,000 tonnes of imported sugar – more than six times the amount of the same period last year.

With the ATIGA in effect, tariffs for raw sugar reduced from 80 to 5 per cent. Similarly, trade tariffs for white sugar also fell to 5 from 85 per cent. This has prompted Thailand to increase its sugar exports to Vietnam drastically.

Data from the MoIT shows that while Thailand exported around 145,000 tonnes to Vietnam in the first eight months of last year, the figure for the same period this year amounts to 860,000 tonnes, which is already nearly three times as much as the total 2019 imports of about 300,000 tonnes from the kingdom.

Moreover, the protectionism of many sugar-importing markets is rendering the competition in the market unhealthy. Pham Hong Duong, chairman of TTC Sugar JSC, commented that, under the ATIGA, the domestic sugar price is being pushed down closer to global levels.

However, Vietnam’s sugar is not competitive with other countries as local production costs are often higher than the price of imported sugar, despite improving manufacturing technologies.

“The most important measure that local companies have to take now is to reduce their costs to compete with imported sugar,” Duong said.

Furthermore, Vietnamese sugarcane farmers rely heavily on state support covering 80-90 per cent of their investment capital and output consumption – support that other crops do not receive.

However, because of this assistance, sugarcane helps farmers to support their families and stabilise their livelihoods. Moreover, although the main sugarcane product is sugar, the plants are also used to produce molasses, fertiliser, refreshment drinks, and even electricity – with some of these outputs directly serving the farmers.

Duong concluded that the biggest challenge at the moment is “to harmonise the benefits for farmers and processing factories to guarantee a stable and long-term supply of input materials,” which, in turn, could help to reduce the costs.

Regional competition

Vietnam’s sugar industry is being heavily influenced by regional competition and their imported goods. Data from the Vietnam Sugarcane and Sugar Association (VSSA) shows that out of the original 41 sugar mills, only 13 are operating with revolving capital, 17 are currently suffering losses, and the remaining 11 have shut their doors entirely.

Domestic sugar production decreased sharply from 1.5-1.6 million tonnes per year on average to just about 700,000 tonnes. Sugarcane farmers like Dao Van Duong are also rapidly diminishing as prices continue to fall amid the competition. While last year, around 300,000 households were still growing sugarcane, their numbers shrunk to only 70,000 this year.

In addition to the challenge that the ATIGA presents, local sugarcane farmers also suffered under the pandemic. To cope with some of the hurdles, Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc issued Directive No.28/CT-TTg in July to emphasise the MoIT’s role in implementing solutions to develop Vietnam’s sugar industry together with other agencies.

Relevant units shall quickly propose the application of trade remedies for imported sugar products following international commitments. However, even with these efforts, the local sugar industry may be further pushed down by the current competition and the side-effects of the pandemic.

Talking to VIR, the VSSA’s acting general secretary Nguyen Van Loc warned that prices for local sugar may fall even further as Thailand continues to sell its sugar products at very low prices. “The situation could even worsen further since Thailand’s government announced on June 30 to financially support this industry with ฿10 billion ($317 million). Backed by this package, the Thai Ministry of Industry announced a sugarcane price of about ฿1,419 ($45) per tonne,” Loc added.

It remains unclear which of Thailand’s sugarcane products are subsidised and then dumped in the Vietnamese market. Nonetheless, according to the VSSA, local sugar demand for direct consumption and further processing is about two million tonnes per year. As imported sugar into Vietnam may reach 1.2 million tonnes in 2020, the local industry is left with just 800,000 tonnes to play with.

The VSSA also said that before the ATIGA took effect, Vietnam’s sugar industry was under great pressure from smuggled sugar. In 2019, Thailand exported more than one million tonnes of sugar to Cambodia, though local consumption capped at around 200,000 tonnes. Thus, the remaining 800,000 tonnes could have been smuggled into Vietnam through trails and openings along the border.

These issues surrounding the ineffective prevention of trade fraud and smuggling may have been another cause for the decline of local sugar production. While in the 2017-2018 crop year, Vietnam produced 1.47 million tonnes, output fell in the following season to just about 1.17 tonnes.

Reassuring farmers

As local authorities are understandably worried amid this daunting scenario, director of the MoIT’s Agency for Foreign Trade Phan Van Chinh last week met with researchers, sugar enterprises, and farmers to find solutions.

“Current government policy focuses on the 35,000 farmers growing sugarcane,” Chinh asserted at the meeting.

In principle, Vietnam does not restrict the import of sugar but aims to mainly do so whenever local production does not meet demand.

“We still have to import sugar, but we must address the issues and interests of farmers,” Chinh reassured.

He has good reason for the comments above, as Vietnam’s sugar market is technically closed to the outside, except for its commitments to the ASEAN. “Vietnam will find several solutions to deal with the local sugar industry’s shortcomings and improve its capacity while protecting local farmers. We also talked to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development to find measures to manage sugar imports amid the new situation,” Chinh said. According to the International Sugar Organization, different from previous years, there is no shortage this year in global sugar supply as the pandemic has slowed down demand around the globe significantly.

Meanwhile, the world’s largest sugar producer, Brazil, is again increasing its output and forecast to produce around 39.5 million tonnes, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

As local sugar producers struggle with regional competition, Tran Cong Thang, director of the Institute of Policy and Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development, reassured that Vietnam is not inferior to Thailand when it comes to some raw materials.

“Since domestic enterprises have been focusing on diversifying their products, investing in technology, and developing material sources in advantageous localities, Vietnam may be able to have an edge over regional competitors if the country also builds up a decent distribution system,” Thanh said.

Nevertheless, even if local authorities manage to improve production and keep up with regional competitors, another enemy is waiting at the gates. The biggest difficulty, not just for sugarcane farmers, is climate change. Currently, its effects are visible as droughts are affecting the industry significantly, and not many farmers are equipped with proper irrigation systems.

In addition, some Mekong Delta provinces where sugarcane is planted massively suffer under inundation and saline intrusion which also negatively impact sugarcane production.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- VNPAY and NAPAS deepen cooperation on digital payments (February 11, 2026 | 18:21)

- Vietnam financial markets on the rise amid tailwinds (February 11, 2026 | 11:41)

- New tax incentives to benefit startups and SMEs (February 09, 2026 | 17:27)

- VIFC launches aviation finance hub to tap regional market growth (February 06, 2026 | 13:27)

- Vietnam records solid FDI performance in January (February 05, 2026 | 17:11)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

- EU and Vietnam elevate relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership (January 29, 2026 | 15:22)

- Vietnam to lead trade growth in ASEAN (January 29, 2026 | 15:08)

- Japanese business outlook in Vietnam turns more optimistic (January 28, 2026 | 09:54)

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version