EU competition in redrawn public procurement landscape

|

| Nguyen Thi Thu Trang, director of the World Trade Organization and International Trade Centre, under the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

In the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA), Vietnam commits to opening part of its government procurement market to EU contractors.

Government procurement, or public procurement, is the act of obtaining goods or services for a public agency, using part of the public budget. In such public procurement, states tend to give priority to buying goods and services from local businesses and units, considering it a good way to ensure the highest benefit for the locals.

This is a popular practice that almost all countries follow. In the US, the “Buy American” scheme applies solely for the purchase of goods and services made by American groups.

A similar act is being applied in other countries, except for those with open market agreements. In some specific cases, only domestic contractors are allowed to compete for the public procurement packages of their countries.

In Vietnam before 2019, before the enforcement of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), there were in principle no foreign contractors freely joining government procurement packages in the country, except for cases of using foreign loans/international funding, or those offering international bidding.

Within the World Trade Organization (WTO), Vietnam is only an observer of the organisation’s Government Procurement Agreement and is yet to make any market-opening commitments in this field.

In the FTAs which took effect before last year, Vietnam also did the same.

|

| Photo: Le Toan |

Bold step towards liberalisation

The EVFTA is not the first time that Vietnam has opened its government procurement market to foreign contractors, with the CPTPP being the first. However, in the EVFTA, the scale of packages that Vietnam permits EU firms to join is significantly wider than that in the CPTPP.

Specifically, in the EVFTA, Vietnam commits to opening government procurement packages for 20 central-level agencies, two localities (Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City), and 42 other units including hospitals and universities. Meanwhile, for CPTPP contractors, Vietnam opened packages in 21 central-level agencies, 38 other units, and no localities.

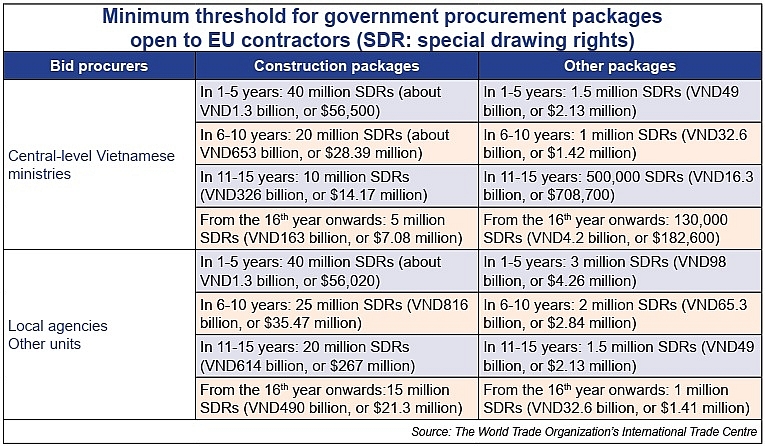

The minimum threshold calculated in special drawing rights (SDRs) of packages that are subject to market opening to EU contractors is also much lower than that in the CPTPP. For example, in the CPTPP, except for construction packages, in the first five years of the enforcement only packages valued at VND98billion ($4.26 million) and higher are open to CPTPP contractors, and starting from the sixth year, the threshold is down to over VND65 billion ($2.83 million).

In the EVFTA, the threshold is applied only for the packages offered by localities and other units in the first 10 years, and then will be reduced by a schedule to over VND32 billion ($1.39 million) starting from the 16th year onward. The minimum threshold of packages for central government procurement is much lower, from VND49 billion ($2.13 million) in the first five years to over VND4 billion ($173,900) from the sixth year onward (see box).

Vietnam’s state budget is modest and so its expenditures therefore are not as big as in other countries. In spite of this, government procurement still makes up a significant part in the country’s total domestic spending. It could be said that the government is the big purchaser of goods and services in Vietnam.

For domestic contractors who had for years dominated the government procurement market, sharing a slice of the cake to EU firms is not good news, especially as EU competitors have strong expertise in capital, professionalism, competitive edge, and international experience.

|

Challenges and opportunities

However, in a broader view, the market opening for EU contractors is not completely a serious threat to Vietnamese contractors.

Firstly, generally the structure of goods and services of the EU does not compete directly with Vietnam. In government procurement, EU contractors mostly have no special interest in goods and services that Vietnamese contractors have advantages in bidding for public procurement contracts such as agroproducts, foodstuff, woodwork, textiles and garments, footwear, and more.

On the contrary, the government procurement packages that EU businesses are forecast to have strong interest in, such as high-tech devices and machinery, are not the top focus and priority among Vietnamese firms. Therefore, direct competition in government procurement packages in Vietnam with the future involvement of EU contractors will not be as tough as expected.

Secondly, although minimum thresholds of government procurement packages that Vietnam commits to open to EU contractors in the EVFTA are lower than in the CPTPP, such remains higher than the common ones in Vietnam, and the schedule to lower it is long. Thus, in the short term, the packages with small and average threshold will yet to face competition from the EU.

Moreover, for some groups of specific and sensitive products like pharmaceuticals and products for national defence, Vietnam has specific market-opening commitments with a significantly slower timeline, and quotas of total contract value reserved specifically for Vietnamese firms.

Even for packages expected to be exposed to competition with EU competitors, this is not all bad news. As to these packages, Vietnam not only promises to open to EU contractors, it also commits to ensure the bidding process and procedures are transparent and meet the high standards of the EVFTA. For genuine Vietnamese businesses, this will help them expel negative phenomena in bidding, thus increasing the opportunities to win bids for them.

The EVFTA even brings about huge opportunities for Vietnamese contractors who are capable enough to access the EU’s giant government procurement market.

The EU’s commitment to open its government procurement market to Vietnam is significant. This may be the reason why it asked Vietnam to make significantly stronger market-opening commitments than in the CPTPP.

In fact, the EU has already made a similar market-opening commitment in the EU-Singapore FTA in this field. However, Singapore is not a direct competitor with Vietnam in the majority of products. The main competitors of Vietnam in the EU market, such as ASEAN and China, are yet to have the rights to approach the EU government procurement market.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Themes: EVFTA & EVIPA

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- VinaCapital launches Vietnam's first two strategic-beta ETFs (February 26, 2026 | 09:00)

- PM sets five key tasks to accelerate sci-tech development (February 26, 2026 | 08:00)

- PM outlines new tasks for healthcare sector (February 25, 2026 | 16:00)

- Citi report finds global trade transformed by tariffs and AI (February 25, 2026 | 10:49)

- Vietnam sets ambitious dairy growth targets (February 24, 2026 | 18:00)

- Vietnam, New Zealand seek level-up in ties (February 19, 2026 | 18:06)

- Untapped potential in relations with Indonesia (February 19, 2026 | 17:56)

- German strengths match Vietnamese aspirations (February 19, 2026 | 17:40)

- Vietnam’s pivotal year for advancing sustainability (February 19, 2026 | 08:44)

- Strengthening the core role of industry and trade (February 19, 2026 | 08:35)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version