Digital transformation: GE embraces digital leader role

|

The issues are not technical, but strategic

The manufacturing industry is in the throes of a major upsurge in innovation. The progressive digitalisation of industry – known as the Industrial Internet – is increasing the efficiency of production processes and generating additional growth. As a result, companies that master these new digitalisation rules can make better decisions, improve process integration, and develop new business designs.

According to Oliver Wyman’s study, entitled ‘Digital Industry – The True Value of Industry 4.0’, the global value-added potential of Industry 4.0 will hit $1.4 trillion by 2030, driven by cost reductions and profit growth. Most technical drivers of the digital transformation have been identified. They include the growing availability of networked machines in production facilities, more extensive 3D printing processes, simulation software, and the almost real-time availability of large data sets (‘big data’).

In this context, companies in the machinery and plant engineering industries will need to address primarily strategic issues, not technological ones.

The principal strategic issue is digital leadership. In the future, who will operate and optimise the systems in a car factory? Will these activities be performed by the company supplying the robots, the automotive manufacturer or a third-party software giant? Who will be capable of analysing the operating data? These questions are all related to the so-called application expertise and are truly the core issues of Industry 4.0. In the future, they will stand at the heart of mass customisation.

Machinery and plant engineering companies can not only boost their share in value creation in their traditional business sectors, but also in related industries by taking process integration into their own hands.

|

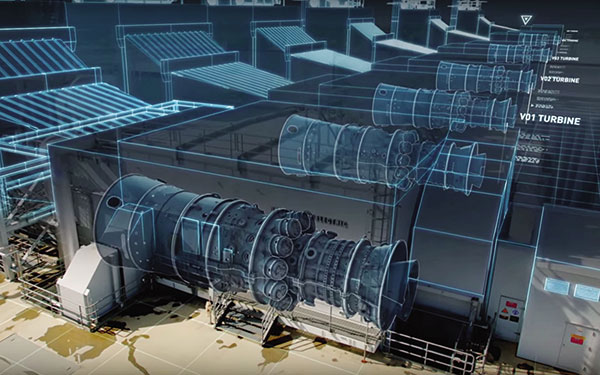

| With total integration with the digital world a necessary step for industry, GE has made a transition to a big data power |

GE has identified nine distinct points across the value chain, ranging from improving research and development efficiency to optimising the production network. The key aspect of digital value is a better understanding of actual customer demand that allows more precise forecasts and smarter pricing based on the customers’ willingness to pay. This potential will be reflected by global margin growth worth $600 billion. Making production more flexible, for example by allowing mass customisation, is the second most important aspect in terms of impact, adding $300 billion.

The advent of the ‘Digital Industry’ will fundamentally transform each and every company in the manufacturing industry. As the trend takes flight, executives, for their part, will be increasingly required to set up more transparent, data-based processes for their decision-making.

However, it seems that only a small number of managers feel that they are well-equipped to meet these new challenges. When surveyed for the study, a typical response from machinery and plant engineering company decision-makers was that there is not enough “creativity to think outside the existing operating models and business designs”. In addition, 86 per cent of the respondents deplored the lack of “in-house software and data capabilities” within their companies. Furthermore, 84 per cent acknowledged that they did not have the necessary “expertise to analyse large data volumes”, nor to derive real insight or recommend tangible improvement measures.

This shows that becoming the kind of firm that can thrive in digital industry is a significant challenge. It will require incumbent industrials to develop skills in data-based insight generation, to upgrade technology, to become more innovative, and to make organisational changes that promote these advances.

Therefore, industrial companies seeking to exploit their digital potential will need to transform many dimensions of their business and operating models and build a broad set of new capabilities.

Companies should not underestimate the urgency of getting this process underway, because it could take a decade or more to make the full transition. Customers’ expectations regarding digitisation will rise at an increasing pace and start-ups or fast-moving incumbents will seize the opportunities. In other words, “laggards will be losers”.

|

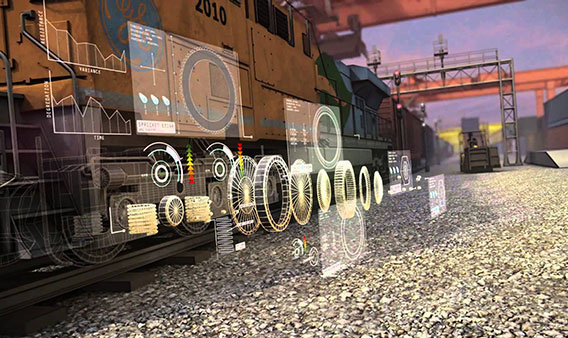

| With its digital technology, GE provides added value to its already-contracted clients |

From hardware to software

GE’s crusade to break open the tide of digitisation started in 2011. In 2008, in the midst of the global financial crisis, the surroundings of GE’s chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt might have seemed like the world was coming down on him, with share prices falling from $60 in 2000 to below $6 in 2008, and the company stripped of its triple-A credit rating by Standard & Poor’s. To top it off, Immelt was forced to cut the dividend for the first time since 1938.

It was then that Immelt started thinking about data. Many GE’s manufactured assets were becoming equipped with sensors to collect information. That often resulted in immense amounts of data: a jet engine, for instance, spits out roughly a terabyte’s worth of everything from fuel usage through heat levels to the size of the specks of dirt that fly through the engine, on a trip across the US. What were GE and its customers supposed to do with all that data?

Immelt considered teaming up with a tech company to create software that would analyse vast amounts of the data, but when the tech company figured that out, what would it need GE for? He thought GE would be better off developing this software on its own. If nothing else, the company would be able to utilise the technology to improve its own productivity, and if things went well GE would be able to sell it as an add-on to service contracts with industrial customers.

|

| Jeff Immelt, GE’s chairman and CEO |

He thus decided that GE needed to start building analytic and big data capability. It was the time when Immelt went after William Ruh, then-vice president at Cisco Systems. Ruh was astonished to get a call from a recruiter representing GE. He thought GE knew nothing about software. But he travelled to Fairfield in January 2011 to meet with Immelt. He was impressed by his vision and took the job. By the end of 2011, GE opened a software center in San Ramon, California.

Convinced that GE needed a cultural revolution, Immelt sought assistance from Eric Ries, a tech entrepreneur and author of “The Lean Startup”, a book that espouses the importance of releasing early versions of products, getting customer feedback, then “pivoting” or changing them if necessary to improve them. Ries helped GE tailor its own version of his methods, which the company calls FastWorks. FastWorks, according to GE, enabled the development of a new gas turbine in a year-and-a-half, rather than the usual five.

At the end of 2013, GE had 750 people working in its San Ramon office and had developed an early version of Predix, an operating system like Windows or Android but for the Industrial Internet. The company developed applications, enabling Predix to ingest and analyse vast amounts of data from sensor-equipped machines.

In April 2015, Immelt announced his plan to sell $200 billion of GE Capital assets within two years. Along with unloading most of its risky financial business, GE struck a deal to sell off its appliance division to Chinese conglomerate Haier and increased its share of the global power industry with its 2015 purchase of Alstom, a French energy company, for $10 billion. As a result, 90 per cent of GE’s profits will come from industrial operations by 2018.

The head count at the San Ramon office is now 2,000. When GE announced plans to open a software division in 2011, it expected to have a team of 400. Today, it has more than 14,000 software engineers, data scientists and designers helping to fuel software development for GE and its customers, and that number is expected to grow in coming years. Software revenue is on track to grow 20 per cent, increasing to more than $6 billion, in 2016, less than a year from the creation of GE Digital.

GE is beginning to sell Predix-based services to customers who design their own industrial equipment. Pitney Bowes is using Predix on its mailing-label machines and letter-sorting devices in corporate mailrooms. Toshiba is using it on elevators. A total of 20,000 developers from GE, partners, developers, and innovators are working on the platform to create industrial apps and solutions.

GE faces competition from all sides. Amazon and Google are getting into the Industrial Internet of Things along with IBM and Microsoft and dozens of small startups. However, knowing that the digital transformation that is underway in the industrial world is one of those times where a company has to get it right or become obsolete, GE seems to have made a smart choice. Only GE brings the combination of industrial domain and software expertise.

“If the ‘industrial’ does not converge with the ‘digital’, it will trigger a collision and we may see more formerly great companies fall by the wayside, while those that get the convergence right rocket to the next level,” said John G. Rice, vice chairman of GE and president and CEO of GE Global Growth Organization. “We are partnering and collaborating with our customers, suppliers, and developers to ensure we are not left on the sidelines.”

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- Addressing Vietnam's energy challenges with aeroderivative gas turbines (February 28, 2023 | 09:33)

- How to sprint ahead in 2023’s worldwide energy priorities (February 08, 2023 | 13:55)

- Boosting Vietnam's grid stability through gas turbine technology (November 22, 2022 | 20:02)

- Healthcare trio collaborates to provide thousands of free breast scans (October 27, 2022 | 17:19)

- GE Healthcare's vision for AI-backed radiology (September 29, 2022 | 11:53)

- GE brand trio to shape the future of key industries (July 19, 2022 | 15:35)

- GE unveiling brand names and defining future (July 19, 2022 | 15:16)

- GE: the shortest route towards sustainability (July 18, 2022 | 08:00)

- Be proactive in an uncertain world (May 20, 2022 | 11:40)

- GE secures first 9HA combined cycle power plant order in Vietnam (May 16, 2022 | 17:06)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version