Assessing risks of inflation for everyday life in Vietnam

|

| Patrick Lenain, senior associate at the Council on Economic Policies |

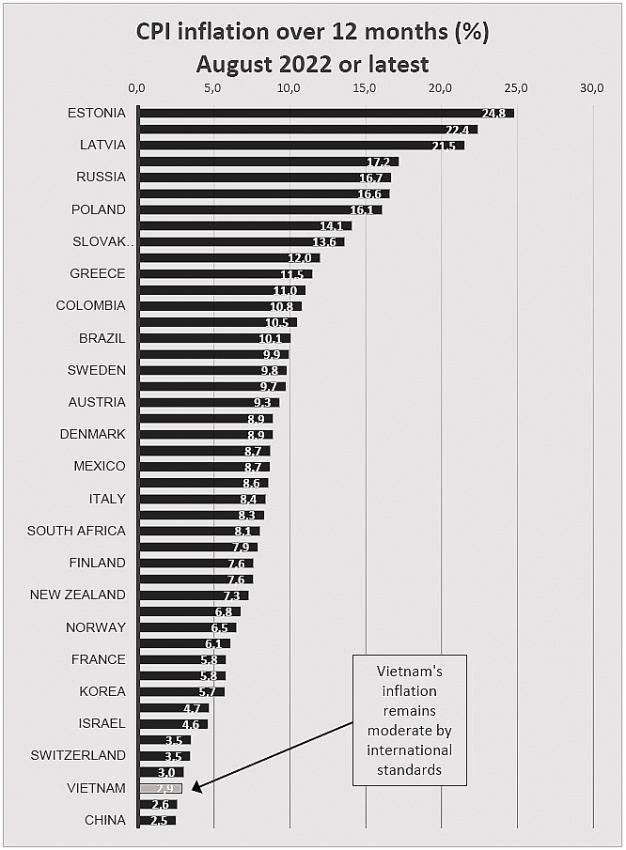

Inflation is high around the world, reaching in some countries levels not seen in 40 years. No less than 15 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) record annual inflation rates above 10 per cent. In a few countries, price increases have even reached levels akin to hyperinflation – about 80 per cent both in Argentina and Turkey.

Today’s inflation is well above the level of 2 per cent targeted both by the European Central Bank and US Federal Reserve. These central banks have started to tighten their monetary policy to send a signal that they remain committed to their low inflation target. The Fed has hiked its policy rate already five times in 2022, and the European Central Bank has raised its policy rate at two meetings. Injection of liquidity in the economy has also been reduced – quantitative tightening has replaced quantitative easing – and central banks’ balance sheets have started to decline. Most observers expect that additional tightening measures will be announced as inflation is not yet under control.

Central banks cannot act against increases in commodity prices. These so-called “supply shocks” – events such as the war in Ukraine or crop failure induced by dry weather – are beyond the reach of central banks. But monetary policy can control core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices.

In July, core inflation reached 6.8 per cent in OECD countries, also well above the central banks’ target. These high rates of core inflation are widely attributed to economic overheating, as support measures introduced during the pandemic continue to stimulate consumer demand.

Whether or not monetary policy tightening will cause a global recession is fiercely debated among economists. But there is no dispute that economic growth needs to slow down in countries with severe labour shortages, such as Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. In these countries, employers have no other choice than to offer higher wages to fill job vacancies. Higher wages risk fuelling higher retail prices and triggering wage-price spirals, a situation that central banks want to avoid.

Lowering impacts

Inflation rates are representative of the average household, but some social groups are hit by even faster increases in the cost of living. Energy prices are 35 per cent higher and food prices are 15 per cent higher than the previous year in OECD countries. For families on a tight budget, with no other choice than to put food on the table and pay energy bills for their cooking, heating and driving, inflation is a very worrying development.

A recent survey found that more than 1.7 million UK households are planning to stop paying their energy bills and, in the United States, 20 million households are behind their bills.

Many governments have stepped in to soften the hit with price freezes, lower VAT rates, and consumer subsidies. Governments have also provided direct income relief with cash transfers, vouchers, higher wages, increased pensions, and more generous social benefits. This is however costly for the public finances, and not all countries have the fiscal space to do it. High food prices are particularly burdensome for low-income families. A composite index of five commodity groups calculated by the Food and Agriculture Organization reached an all-time high in March. Food prices have declined since then, but they remain particularly high for meat, dairy products, and cereals.

In the United States, according to statistics published by the Department of Labour, grocery prices increased by 13.5 per cent in August from the previous year, with particularly large increases in the price of eggs (up about 40 per cent), and butter and margarine (up about 29 per cent). This inflicts a severe hit on low-income American families: the poorest quintile group allocates 27 per cent of its spending to food, compared with only 7 per cent among the richest income quintile.

Elsewhere in the world, high food prices have an even more harmful impact. In developing countries, food expenditure can take up to 44 per cent of the consumption basket. When food prices soar, households have no other choice than to cut back on their food purchases. With about 800 million people undernourished in 2020 (one-tenth of the world population), the present food price surge could rapidly trigger a humanitarian crisis.

In contrast to these international developments, inflation has remained low in Vietnam. The pace of price increases has picked up a bit from the previous year – reaching 2.9 per cent in August – but it remains well below international levels. Inflation remains also below the level of 4 per cent targeted by the State Bank of Vietnam.

Inflation has been kept low in Vietnam over the past decade. Monetary policy, exchange rate management, and fiscal policy have been prudent, with a focus on stability.

Markets have been open to more intense competition, putting pressure on sales prices. Free trade agreements with foreign countries, lower import tariffs, and large inflows of foreign direct investment have improved the supply of goods.

Finally, about 20 per cent of prices are administered by the government such as fuels, electricity, water, and also tuition fees. The government controls also the price of rice.

|

On the brink

Vietnam’s recent success with low inflation owes a lot to the stability of food prices.

According to Vietnam’s General Statistics Office, foodstuff and grain prices increased by only 2.3 per cent in August from the previous year, well below increases in other countries. The global surge in food prices has not passed through to domestic consumer prices thanks to Vietnam’s plentiful domestic supplies, lower prices of pork, and a preference for rice, which has increased less than other grains like wheat.

However, even moderate food price increases may inflict severe damage. Vietnam has successfully reduced food poverty and already achieved the UN Sustainable Development Goal for hunger, but undernourishment has not been eliminated – 6.7 per cent of the Vietnamese population remains undernourished accordingly to the World Bank.

In addition, according to UNICEF, around 230,000 under-5s suffer from severe acute malnutrition annually, especially in ethnic minorities, which can result in stunting and even child mortality. For people on the brink of hunger, even small food price increases can rapidly lead to poor health. Attention needs to be paid so that these groups are not left behind.

Transport prices have increased more rapidly than food prices – almost 9 per cent annually in August – reflecting the passthrough of global energy prices into gasoline prices.

After this temporary acceleration, transport prices will show a slower pace as gasoline prices have fallen rapidly: by mid-September, gasoline prices had fallen well below the peak reached last June. This reflects the downward trend in global energy prices.

With gasoline prices now back to more affordable levels, tax cuts decided earlier to soften the hit will have to be reconsidered. Environmental protection taxes (EPT) were cut in half last April, and the National Assembly adopted another decision in July to further lower it still. Similar EPT cuts were applied to diesel, mazut, kerosene, and lubricants.

Such tax cuts are costly for the public budget, they benefit mostly richer individuals who can afford to buy expensive vehicles, and they encourage fuel consumption – thus impeding the country’s decarbonisation.

While recent inflation trends have been encouraging in Vietnam, it is soon to claim victory. The military conflict in Ukraine could worsen in unpredictable ways, jeopardising the fragile agreement allowing grain shipments through Black Sea ports.

China’s economy, currently weakened by recurrent pandemic lockdowns, could rebound strongly if it soon decides to drop its current pandemic strategy. The reopening of China and the lifting of all health restrictions would stimulate the economy, putting once again pressure on international commodity markets.

Global monetary tightening could cause financial distress in highly indebted emerging market economies, with contagion effects depressing the external value of currencies such as VND.

Prudent macroeconomic policies combined with ambitious structural reforms and social inclusiveness have allowed Vietnam to keep inflation well below international levels. Keeping up with this sound strategy will consolidate its success.

| Inflation risks pose questions for exchange rate policy In response to the recent Fed’s interest rate hike, the State Bank of Vietnam is predicted to tighten its monetary policy in an attempt to curb inflation, with a focus on controlling the exchange rate. |

| Growth forecasts take price risks into account Despite positive forecasts from international organisations on Vietnam’s economic recovery, there are still concerns related to inflation and growth that need solutions and directions from the government. |

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Citi economists project robust Vietnam economic growth in 2026 (February 14, 2026 | 18:00)

- Sustaining high growth must be balanced in stable manner (February 14, 2026 | 09:00)

- From 5G to 6G: how AI is shaping Vietnam’s path to digital leadership (February 13, 2026 | 10:59)

- Cooperation must align with Vietnam’s long-term ambitions (February 13, 2026 | 09:00)

- Need-to-know aspects ahead of AI law (February 13, 2026 | 08:00)

- Legalities to early operations for Vietnam’s IFC (February 11, 2026 | 12:17)

- Foreign-language trademarks gain traction in Vietnam (February 06, 2026 | 09:26)

- Offshore structuring and the Singapore holding route (February 02, 2026 | 10:39)

- Vietnam enters new development era: Russian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 10:08)

- 14th National Party Congress marks new era, expands Vietnam’s global role: Australian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 09:54)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version