Acute challenge for world to tackle climate crisis at COP27

More than 30,000 delegates, including representatives from about 200 nations or territories, will gather on November 6-18 in the Egyptian town of Sharm el-Sheikh for COP27, in order to thrash out details on how to slow global warming and support those already feeling its impacts.

|

| Acute challenge for world to tackle climate crisis at COP27 |

Most mainstream analysis acknowledges that 2021’s COP26 in Scotland did not make enough progress to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. By the end of the decade, the world is expected to miss the Paris Agreement target to prevent the world’s average temperature from rising 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Scientists and UN officials have warned that exceeding that level will have catastrophic consequences, including devastating sea-level rise, longer and more intense heat waves, and widespread species loss.

But with the world dealing with the fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, along with soaring food and fuel prices and stuttering economic growth, questions are arising over whether they will act quickly enough. The freeze in relations this year between top greenhouse gas emitters China and the US also does not bode well, experts said.

A United Nations report released in October showed that most countries are lagging on their existing commitments to cut carbon output, with global greenhouse gas emissions on track to rise 10.6 per cent by 2030 compared with 2010 levels. Scientists said that emissions must drop 43 per cent by that time to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

Only 24 countries and territories have submitted new or updated emissions-cutting plans since COP26, even though all had committed to doing so, according to the UN climate agency. A few countries, including Chile, Mexico, and Turkey, are expected to release new plans during the Egypt conference, but it is unclear if any major developing economies like China and India will also do so.

Climate stocktake

According to the event’s vision statement, COP27 will be about moving from negotiations, and “planning for implementation” for all these promises and pledges made.

Besides reviewing how to implement the Paris Rulebook, the conference will also see negotiations regarding some points that remained inconclusive after COP26.

These issues include “loss and damage” financing so that countries at the frontlines of the crisis can deal with the consequences of climate change that go beyond what they can adapt to, and the fulfilment of the promise of $100 billion every year from adaptation finance, from developed nations, to low-income countries.

The negotiations will also include technical discussions to specify the way in which nations should practically measure their emissions so that there is a level playing field for everyone.

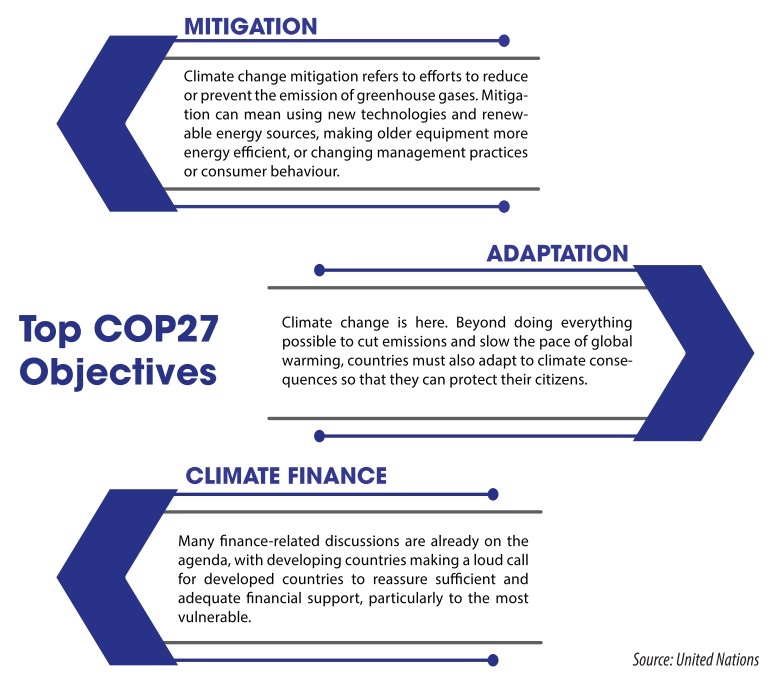

All these discussions will pave the way for the first Global Stocktake at COP28, which in 2023 will assess the global collective progress on mitigation, adaptation, and means of implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Perhaps the bigger picture is of a need for more transformative change in global economic systems. Alessandra Giannini of Columbia University wrote a fortnight ago, “I hope to see debate emerge about the deep connection between global inequality and climate change. The exploitation of fossil fuels that has led us to the edge has its roots in a global economic system where winners exploit losers in a never-ending quest for growth. Climate change cannot be halted unless we redress this inequality.”

In terms of the Asia-Pacific region, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has announced plans to launch several flagship initiatives at COP27.

During the event, the ADB will launch an Asia-Pacific water resilience initiative, aimed at promoting water management in the region, and a finance hub to restore ocean health, build coastal resilience, and develop sustainable blue economies.

The bank will also launch its “just transition” support platform to ensure that the benefits of the shift to low-carbon, resilient economies are shared equally. In addition, the ADB is piloting a finance facility for climate in Asia-Pacific, which will use guarantees and grant contributions from donor countries and philanthropies to leverage $4 for every $1.

The last 12 months have highlighted the negative human impact on climate, particularly in Asia-Pacific. Flooding in Pakistan has been historically devastating, as has extreme drought in China, tropical cyclones in the Pacific Islands, and typhoons in the Philippines.

Anjal Prakash of the Bharti Institute of Public Policy at the Indian School of Business emphasised that the impacts of climate change are happening now, and are being disproportionately felt in the Global South. “Be it floods in Bangladesh, India, or Pakistan, we have seen devastating images of how the poor and marginalised are suffering,” Prakash said. “A large part of the poor in South Asia live below the poverty line and their lifestyles are carbon negative. They are the first ones to be affected by the rapidly changing climatic conditions and do not have capacities to cope.”

The ADB’s climate envoy Warren Evans added, “We cannot avoid all the impacts of climate change so we have to focus on building resilience of the most vulnerable communities. COP27 will focus on scaling-up adaptation solutions and mobilising and strengthening access to financing for adaptation.”

Evans said that the ADB raised its ambition for climate change financing for 2019-2030 from $80 billion to $100 billion, of which $34 billion is marked for adaptation. “It is time to step up and mobilise the kind of resources, with the kind of conditions, that allow countries to really use those resources to adapt to and become more resilient to climate change,” he added.

|

National responsibilities

But many of the plans involve action from the biggest emitters, such as the US and China.

“Climate-related communication between China and the US remains stagnant. Even if they resume conversation or even negotiation, it may be difficult to see cooperation push global climate actions forward again,” said Kevin Mo, principal at the Innovative Green Development Program based in China.

During 2021 climate talks, the US and China produced a joint statement on a variety of collaborations, from carbon capture and storage, renewable energy development, methane emission reductions, and cross-border carbon trading. Further, China committed to develop a national action plan on methane emission reduction before COP27, but the plan is yet to be published.

In upcoming talks, China is expected to seek a new partnership with developing countries to drive renewable energy investments, while pushing back on “green barriers”, namely trade barriers built for environmental protection.

Proposals for a global clean energy partnership emerged in October, with China committing to channel investments and foster collaboration for renewable energy deployment. COP27 could be the ideal venue to negotiate with potential partner countries.

Meanwhile, the EU – consisting of 27 member countries with the third-largest emissions in the world – is trying to mobilise the main emitters to set more ambitious climate targets.

In a document released after EU environment ministers met in Luxembourg on October 24, member states called for increased global efforts to achieve the targets set out in the Paris Agreement. The EU’s current target is to reduce net emissions by 55 per cent by 2030, compared with 1990 levels, and EU officials pledged to raise the target as soon as possible.

Notably, the EU agreed to put the issue of loss and damage on the agenda of COP27, discussing compensation measures related to damages caused by floods, sea-level rise, and other impacts caused by climate change, to the poorest countries in the world. This has remained a contentious issue for many years, and the agreement of EU ministers to put it on the agenda of COP27 could be considered a breakthrough.

Developing countries are constantly pressuring the world’s top-emitting economies, to gradually abandon their opposition to claims, in cases of damage caused by the effects of climate change.

Gabon’s environment minister Lee White told The Guardian that governments like those in the EU were not yet behaving as if global heating was a crisis. He said the $100 billion of promised climate finance from rich nations was not reaching poor countries, which was driving distrust in the UN climate process.

“With everything that’s happened in the last year in the Horn of Africa and Pakistan – those places really count,” White said. “With drought and fires in Europe, and the New York subway becoming Niagara Falls, we might be at a point where things are getting bad enough that developed nations start taking the climate more seriously,” said White. “It’s a horrible thing to say, but until more people in developed nations are dying because of the climate crisis, it’s not going to change.”

At the very least, negotiators will be heading to COP27 with the benefit of ever-growing scientific evidence of the issue. Fred Tangang of the National University of Malaysia pointed out that Southeast Asia is considered one of the most exposed regions to climate change.

“Due to the uncertain prospect of hitting the targets, countries in the region will need to focus more on adaptation measures to increase climate resilience,” Tangang said. “Information from sources such as CORDEX Southeast Asia’s regional downscaling exercises will hopefully provide policymakers and practitioners in this region with evidence they can use to devise science-based adaptation measures alongside sustainable development. I hope to see more recognition of such opportunities at COP27.”

| Vietnam reiterates strong commitments at COP27 Vietnam is engaging in negotiations regarding issues in which the country needs international support, such as financing and technical assistance to draft plans in energy transition and assess renewable energy potential. |

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Tag:

Tag:

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Trung Nam-Sideros River consortium wins bid for LNG venture (January 30, 2026 | 11:16)

- Vietnam moves towards market-based fuel management with E10 rollout (January 30, 2026 | 11:10)

- Envision Energy, REE Group partner on 128MW wind projects (January 30, 2026 | 10:58)

- Vingroup consults on carbon credits for electric vehicle charging network (January 28, 2026 | 11:04)

- Bac Ai Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant to enter peak construction phase (January 27, 2026 | 08:00)

- ASEAN could scale up sustainable aviation fuel by 2050 (January 24, 2026 | 10:19)

- 64,000 hectares of sea allocated for offshore wind surveys (January 22, 2026 | 20:23)

- EVN secures financing for Quang Trach II LNG power plant (January 17, 2026 | 15:55)

- PC1 teams up with DENZAI on regional wind projects (January 16, 2026 | 21:18)

- Innovation and ESG practices drive green transition in the digital era (January 16, 2026 | 16:51)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version