Unearned currency label unlikely to stick

|

| Michael Kokalari, chief economist at VinaCapital |

The US government normally does not accuse its trading partners of manipulating the value of their currencies in order to gain an unfair advantage in selling their products in the US market. This was partly because being designated as a “currency manipulator” did not entail severe consequences.

This changed in April 2020, when the Trump administration issued new guidelines encouraging the US Department of Commerce to impose tariffs on countries the US Treasury Department has designated as currency manipulators, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

The US Treasury put Vietnam on the monitoring list of potential currency manipulators in early 2020, but most economists had not expected it to actually brand Vietnam as a currency manipulator because the economic justifications supporting that designation are not very strong, and because Vietnam has a potentially critical role in helping the US achieve its regional geopolitical goals.

In light of the Treasury’s unexpected and arguably unjustified action, many economists/analysts now believe that there is a real risk of temporary tariffs on Vietnamese exports to the US and that the Trump administration’s motivation to label Vietnam a currency manipulator was primarily spawned by domestic political considerations rather than by concerns about US-Vietnamese economic relations.

Further to the first point, it is very likely that the Biden administration would undo any major sanctions that Trump imposes on Vietnam. However, it could take months for any tariffs on Vietnamese exports to the US to be removed, for a variety of reasons.

Politically motivated tariffs

There are strong arguments against designating Vietnam a currency manipulator, and the US Treasury’s own report even highlights several of these arguments. For that reason, we believe that any potential punitive action by the Trump administration on Vietnam would be at least partly motivated by a desire to impede the incoming Biden administration’s ability to reverse Trump’s “America First” policy.

Furthermore, Trump has issued many new sanctions on China in recent weeks, including prohibitions on specific individuals and companies, which prompted a senior analyst at the CSIS to comment that Trump is leaving “a whole pile of trade problems with China” for Biden.

Biden will need to expend political capital to undo Trump’s trade-related actions. We believe Trump’s strategy is to leave such a large pile of trade-related issues behind that the incoming administration will exhaust time and effort to undo all of Trump’s sanctions on both China and Vietnam. The net result will be that at least some of Trump’s key sanctions against China are likely to remain in place after he leaves office.

|

The case against tariffs

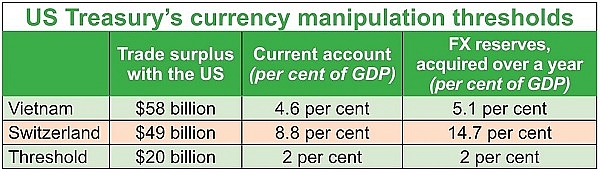

The US Treasury has three quantitative criteria that it uses to determine if a country is a “currency manipulator”. First, the country has a $20 billion trade surplus with the US. Second, the country has an overall 2 per cent of GDP current account surplus. Third, the country’s central bank accumulated 2 per cent of GDP worth of foreign exchange (FX) reserves over a one year period (see table).

In addition to the numerical criteria, the Treasury also uses qualitative criteria, the most important of which is the Treasury officials’ own judgment in determining if that country’s central bank acquired FX reserves in order to depreciate the value of its own currency or to lift that country’s FX reserves up to a prudent level.

The table shows that both Vietnam and Switzerland met the quantitative criteria for being considered a currency manipulator in June 2020.

The Treasury’s report to the US Congress asserted that Vietnam’s FX rate management in the year ending in June 2020 aimed to “gain unfair competitive advantage in international trade”, but this report also contained powerful arguments against Vietnam being considered a currency manipulator. Regarding Vietnam’s trade surplus with the US, the report implicitly acknowledged that one reason the trade surplus surged in recent years was that the administration’s instigation of the US-China trade war prompted companies to shift production from China to Vietnam.

Furthermore, the report acknowledged that fraudulent transshipments also account for a part and also noted that the Vietnamese government had taken effective measures to crack down on transshipments from China.

Regarding the State Bank of Vietnam’s (SBV) accumulation of FX reserves over one year, the US Treasury stated that Vietnam’s FX reserves were 24 per cent below the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) recommended level at the beginning of 2019, and hinted that the reserves held by the SBV are likely to be more-or-less in line with the IMF’s recommended level at the end of 2020.

The IMF computes a recommended level of FX reserves for individual countries using its Assessing Reserve Adequacy (ARA) methodology. The Treasury’s report contained sufficient details about Vietnam’s ARA that enable “back of the envelope” calculations showing that the amount of FX reserves that the SBV bought over 2019-2020 were necessary to bring the country’s FX reserves up to a minimum, prudent level.

The US government has reportedly asserted that the VND is about 5 per cent undervalued, so the easiest way for the SBV to respond to the accusation that Vietnam is a “currency manipulator” would be to allow the value of the VND to start appreciating against the US dollar.

VinaCapital forecast for over a year that VND will begin a sustained, multi-year appreciation, starting from 2021. The US Treasury’s designation of Vietnam as a “currency manipulator” makes it even clearer to us that the VND will appreciate by 3-4 per cent against the USD next year.

Next, potential temporary tariffs discussed above would not be good for the Vietnamese economy but tariffs could actually raise foreign investors’ awareness that the country’s growing economic power compelled the US to take punitive action against it; and we also think the “optics” of Vietnam being lumped in with Switzerland can only raise Vietnam’s perception in foreign investors’ eyes.

Finally, even if the US were to impose 10 per cent tariffs on all of Vietnam’s exports, it is unlikely that foreign-invested companies would be dissuaded from setting up new factories in Vietnam. That is because factory wages in Vietnam are far below most of the potentially competing countries for Vietnam’s foreign investment inflows, and are one-half to two-thirds below China’s factory wages.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Banking sector targets double-digit growth (February 23, 2026 | 09:00)

- Private capital funds as cornerstone of IFC plans (February 20, 2026 | 14:38)

- Priorities for building credibility and momentum within Vietnamese IFCs (February 20, 2026 | 14:29)

- How Hong Kong can bridge critical financial centre gaps (February 20, 2026 | 14:22)

- All global experiences useful for Vietnam’s international financial hub (February 20, 2026 | 14:16)

- Raised ties reaffirm strategic trust (February 20, 2026 | 14:06)

- Sustained growth can translate into income gains (February 19, 2026 | 18:55)

- The vision to maintain a stable monetary policy (February 19, 2026 | 08:50)

- Banking sector faces data governance hurdles in AI transition (February 19, 2026 | 08:00)

- AI leading to shift in banking roles (February 18, 2026 | 19:54)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version