The non-linear future of new global value chains

|

| Nguyen Minh Cuong |

Supply chains and value chains have become increasingly interchangeable. Value is added in almost every stage of the supply chain and, vice versa, the value chain is comprised of interrelated supply change stages from suppliers and manufacturers to customers.

Global value chains (GVCs) have been the most predominant conduit of global trade and important channels for technology diffusion, and were the driving force of globalisation in the 1990s. Rapid evolution of GVCs in the 1990s was driven by profound trade liberalisation measures, which resulted in sharp reduction of tariff barriers to trade.

The establishment of the World Trade Organization in 1995, the shift from import-substitute industrialisation to export-oriented growth, and the proliferation of regional trade agreements and free trade agreements (FTAs) fuelled global trade liberalisation. Significant advances in transport and communications in that decade allowed the fragmentation of production networks across borders, and in turn the spread of GVCs facilitated the diffusion of technology to GVC-participating countries. Multinational corporations played a central and dominant role in the spread of GVCs in the global economy.

Developing countries have significantly benefited from GVCs through greater access to global markets, reduction of costs, knowledge and technology transfer, an improving business environment, and strengthening domestic capabilities.

The benefits of GVCs are not automatic and can be overweighed by multiple challenges if they are not well-managed by the host countries. Technology spill-over and upgrading would not be realised if the participating countries in GVCs only stay at the lowest stage of the value chain.

However, the move up the value chains would require substantial investment in skill enhancement and technology improvement, which are often the key impediments of developing countries and small firms to integrate with GVCs.

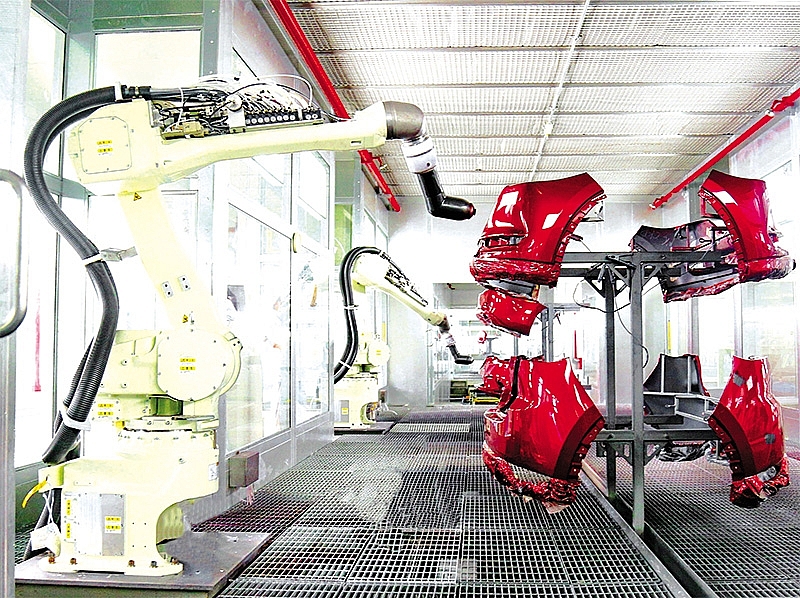

These impediments are further compounded with the new generation of GVCs under the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The traditional GVCs in which suppliers-producers-consumers are linked in a linear fashion are being reconfigured and reshaped through the rapid evolution of Industry 4.0 with advanced information technology such as Big Data analytics, the Internet of Things, Artificial Intelligence, and robotics.

A linear GVC is being replaced by a more integrated and digitalised network supply chain in which information flows from and to different directions. Cost reduction and efficiency gains are significant by the new generation of GVCs in the Industry 4.0 era.

However, the technological sophistication of the new generation of GVCs and the high level of skillset requirements make it more challenging for developing countries and small businesses to move up to higher stages of value chains.

Recently, the transformation of GVCs has been further complicated with the on-going trade war between the United States and China. It has disrupted global trade flows and GVCs have been therefore severely affected.

|

| The Fourth Industrial Revolution is bringing with it more integrated and digitalised network supply chains, Photo: Le Toan |

Since the beginning of doi moi in 1986, Vietnam’s economy has rapidly integrated with the global economy. Foreign trade is now about twice the country’s GDP. Vietnam is now involved in 12 FTAs that helped the economy become embedded in GVCs. However, the country’s participation with these chains have been largely driven by foreign businesses.

The country’s private enterprises, predominantly represented by small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), numbering more than half a million in 2017 and contributing nearly half of GDP, hardly partake in GVCs.

Low quality is the key constraint that hinders the domestic private sector in joining these global chains. The low-quality problem has become increasingly acute when technical, quarantine, environmental, and health requirements become more stringent as Vietnam is expanding its market access domestically and globally.

One of the underlining causes that have resulted in low-quality products of the domestic private sector is limited capability to innovate and adapt new technology.

The World Bank’s recent Enterprises Survey indicated that product innovation in Vietnam appears more often than other countries aiming at reducing costs and less often at introducing new functions.

Also, relatively few Vietnamese companies appear to be spending on the purchase or licensing of inventions and knowledge for development of new products and processes.

Limited access to finance due to stringent collateral requirements by banks, constrained banking procedures, and lack of well-functioning capital markets are other factors impeding the domestic private sector in improving their product quality.

Despite multiple mechanisms to provide finance, such as the SME Development Fund, state-owned commercial banks, credit guarantee funds, the Vietnam Development Bank, and the Women’s Union and Farmers’ Union, access to such finance remains a critical constraint to quality improvement.

Finally, skill shortages in both technical skills and managerial competency hinder private Vietnamese businesses from improving quality. ManpowerGroup’s recent survey showed that only 11 per cent of Vietnamese companies can meet skill requirements. It points to the end of the “low cost – low skills” era of Vietnam’s development, and the country has to become a high-skilled economy if it wants to catch up with the Industry 4.0 generation of GVCs.

There is also a lack of large domestic private enterprises (LDPEs) which can lead SMEs in the integration with GVCs. Large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were initially expected to drive the industrialisation process and facilitate SME integration with GVCs. However, the inefficiency of some SOEs has prompted the need for LDPEs to fill the gap.

To address the underlining causes of low quality, policy measures would need to support adoption and innovation of technology by enabling the domestic private sector in identifying, acquiring, and adopting cutting-edge technologies.

Enforcement of current regulations on finance is important to strengthen access to finance for domestic businesses. In addition, innovative financing models can be explored, including credit for purchasing and leasing capital equipment, trade finance, supply chain finance, finance for market and product, working capital finance, and greater role of financial intermediaries.

Skills development requires more comprehensive and integrated solutions that can bring together all stakeholders to strengthen the quality of graduates.

Greater participation of the private sector in technical and vocational training is critical to make the training more demand-oriented. Conducive environment for development of LDPEs is critical to create greater linkages with GVCs. These combined policy measures would ensure the improvement of quality of the domestic private sector and consequently their entering into GVCs.

Most importantly, the development of the GVCs in Vietnam should be embedded within a holistic industrialisation strategy rather than having them treated as preferential entities in the economy with special privileges and incentives. In so doing, Vietnam could address “dual economy” characteristics and make economic growth more sustainable and inclusive.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Citi economists project robust Vietnam economic growth in 2026 (February 14, 2026 | 18:00)

- Sustaining high growth must be balanced in stable manner (February 14, 2026 | 09:00)

- From 5G to 6G: how AI is shaping Vietnam’s path to digital leadership (February 13, 2026 | 10:59)

- Cooperation must align with Vietnam’s long-term ambitions (February 13, 2026 | 09:00)

- Need-to-know aspects ahead of AI law (February 13, 2026 | 08:00)

- Legalities to early operations for Vietnam’s IFC (February 11, 2026 | 12:17)

- Foreign-language trademarks gain traction in Vietnam (February 06, 2026 | 09:26)

- Offshore structuring and the Singapore holding route (February 02, 2026 | 10:39)

- Vietnam enters new development era: Russian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 10:08)

- 14th National Party Congress marks new era, expands Vietnam’s global role: Australian scholar (January 25, 2026 | 09:54)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version