The capacity to change amid crisis

|

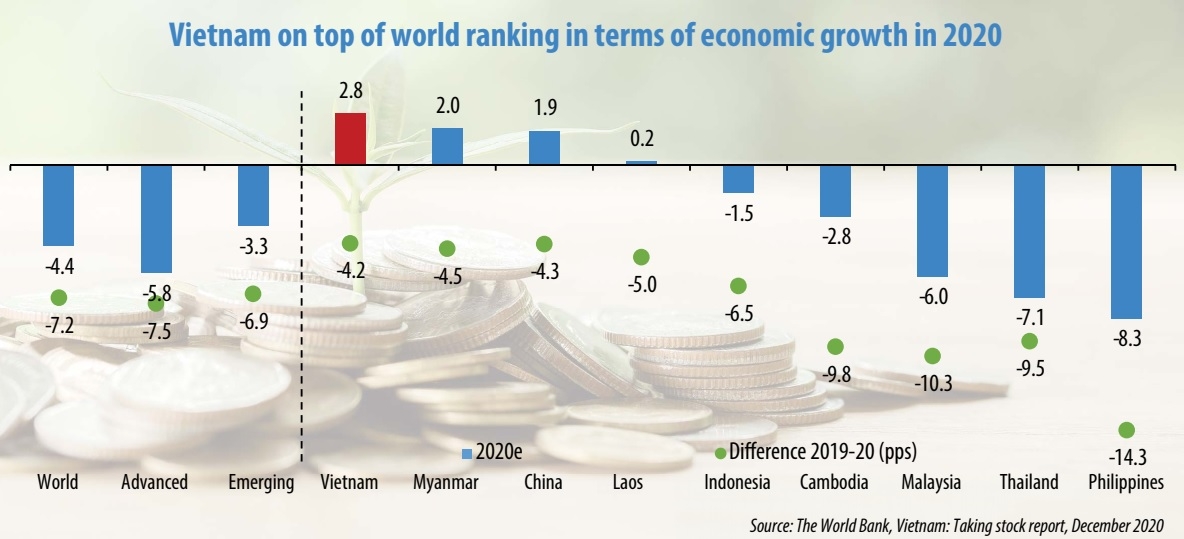

With the number of infections and deaths kept at minimal levels and a GDP growth rate that is estimated to have reached almost 3 per cent in 2020, the country has been an outlier in a gloomy world (see graph).

Vietnam’s capacity to change or to adapt when confronted with a crisis was apparent in at least three different but complementary ways during 2020. Firstly, it moved quickly and boldly to handle the pandemic. Secondly, the government shifted both its monetary and fiscal policies to provide the necessary breathing space to the private sector and to stimulate the domestic recovery. Thirdly, it accelerated reforms to take advantage of global trends emerging from the pandemic, by increasing its footprint in the global economy and by encouraging its digital transformation.

While these changes have shaped Vietnam’s resilience, they are not sufficient unless the country addresses its environmental and climate challenges, which may rapidly threaten the country’s ambitious goal to become a high-income economy by 2045.

By all standards, Vietnam has managed the COVID-19 crisis very well, deservedly receiving a great deal of attention from local and international media. What is perhaps less understood is that the government implemented measures by using its traditional strengths of solidarity and enforcement but also its willingness to innovate through modern digital technologies.

Targeted measures

Early in the process, the prime minister created a national committee that provided the vision but also the necessary coordination mechanisms across ministries and between national and provincial governments, building a strong sense of direction and supplanting complicated existing intra-governmental mechanisms.

The authorities developed an online reporting system to monitor suspected and confirmed cases, including details to trace potential risks of transmissions. The collected information was used to establish strict but targeted quarantine measures and was shared almost in real time with a broad audience through digital platforms and non-traditional methods.

This last step, unusual for Vietnam, helped send the right signals to the population, which accepted the measures and modified their behaviour accordingly.

The external sector – Vietnam’s main driver of economic growth over the past decade – also benefited. In 2020, the country reported not only its highest merchandise trade surplus ever but also accumulated significant international reserves.

Such positive developments were somewhat unexpected at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis when Vietnam was perceived as highly vulnerable to a global economic downturn and the closure of international borders.

Investors from outside the country have continued to come, and merchandise exports to increase even though at a slower pace than in 2019. The management of the COVID-19 crisis has been Vietnam’s best promotional tool, encouraging foreign companies to reallocate their production activities to the country.

Adapting to the new context

After three years of fiscal consolidation, the authorities acted decisively and accelerated the disbursement of the public investment programme, which increased by about 40 per cent between January and September 2020, compared with the same period a year ago.

They also implemented a series of compensatory measures on taxes and social protection but, perhaps, with less conviction due to the relatively limited long-run impacts of the coronavirus on businesses and people. Concurrently, like most central banks, the State Bank of Vietnam eased its monetary and credit conditions to provide breathing space to the affected private sector.

Looking ahead, Vietnam’s prospects appear positive. The latest World Bank projections are that the economy will grow by 6.8 per cent in 2021, and thereafter stabilise at around 6.5 per cent. This projection assumes that the COVID-19 crisis will be gradually brought under control, notably through the introduction of an effective vaccine.

In this baseline scenario, as economic recovery firms up, the accommodative monetary and fiscal policies adopted in response to the crisis are expected to be unwound so the authorities will be able to balance between supporting economic growth and managing inflation, while closely monitoring the health of the financial sector and public debt levels.

That said, the magnitude and duration of the pandemic, as well as its economic implications, are difficult to predict and, for that reason, Vietnam should be ready for further policy changes to address the three potential risks.

The first is fiscal risk – the government may need to identify new sources of funding that would require substantial reforms in public financial management, tax collection, and debt as well as asset management.

The second is that the financial sector, especially commercial banks, is not immune to the pandemic. The main danger is that an increasing number of borrowers will gradually default on their debt, raising the proportion of problematic loans for banks.

Thirdly, social risks could also arise from people and businesses that are now in financial distress because of the pandemic. On average, the shock has been well absorbed by the domestic economy but, as in every crisis, there have been winners and losers. The government should pay immediate attention to victims generally not covered by existing social programmes and are in danger of being left behind.

Accelerating reforms

Despite the success achieved over the past few decades, the authorities have decided to adjust their growth model. If the road from a poor to a middle-income economy occurred through the accumulation of more physical and human capital and the use of natural resources, the transition from middle to high income will be mainly through efficient use of existing resources.

If managed well, Vietnam can emerge stronger from the COVID-19 crisis than before. The successful management of the pandemic to date has already enabled the country to capture a larger share of global trade and foreign direct investment during 2020. The revamping of global value chains provides Vietnam a unique opportunity to position itself, as international corporations and governments are increasingly seeking to diversify their sources of production.

This move has already started, as several existing multinationals have moved part of their production facilities to Vietnam, while new ones have expressed interest in relocating. The challenge for Vietnam would not necessarily be to attract more investors, but to optimise the synergies with domestic suppliers and distributors for the growing local market.

The economy of tomorrow will become increasingly contact-free. While Vietnam was arguably lagging behind more advanced countries in digitalisation, the pandemic has been a catalyst. Over the past few months, local businesses have accelerated their digital development as their customers switch from physical retail towards e-commerce.

The government has also fast-tracked its efforts, and between March and November last year, increased 11-fold the number of e-services integrated into the National Portal.

Addressing the environment

Policymakers have also increasingly recognised that Vietnam’s future will require greater attention to the management of the country’s natural resources and to rising climate risks, which are direct threats to the country’s aspiration of becoming a high-income economy.

Yet, despite the high-level commitment, measurable progress has remained elusive: air pollution continues to worsen in main cities, rising ocean waters are invading the Mekong Delta, and natural disasters are becoming bigger and more frequent along the coast as recently demonstrated by the series of tropical storms that hit Vietnam’s central region during last October and November.

Today, Vietnam stands at a crossroads of COVID-19 recovery. It needs to choose between a business-as-usual path and a green and clean recovery path to help address the impacts of future pandemics or climate and disaster risks and build a resilient future. Such a decision will require new policies and investments. It will also transform doing business and consumption patterns. Yet, history has demonstrated that Vietnam is not afraid of change. The time to act is now.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Foreign leaders extend congratulations to Party General Secretary To Lam (January 25, 2026 | 10:01)

- 14th National Party Congress wraps up with success (January 25, 2026 | 09:49)

- Congratulations from VFF Central Committee's int’l partners to 14th National Party Congress (January 25, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th Party Central Committee unanimously elects To Lam as General Secretary (January 23, 2026 | 16:22)

- Worldwide congratulations underscore confidence in Vietnam’s 14th Party Congress (January 23, 2026 | 09:02)

- Political parties, organisations, int’l friends send congratulations to 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:33)

- Press release on second working day of 14th National Party Congress (January 22, 2026 | 09:19)

- 14th National Party Congress: Japanese media highlight Vietnam’s growth targets (January 21, 2026 | 09:46)

- 14th National Party Congress: Driving force for Vietnam to continue renewal, innovation, breakthroughs (January 21, 2026 | 09:42)

- Vietnam remains spiritual support for progressive forces: Colombian party leader (January 21, 2026 | 08:00)

Tag:

Tag:

Mobile Version

Mobile Version