Encouraging mobile money to stem the spread of COVID-19

Mobile money has three main characteristics. First, the service is available to customers without bank accounts (the unbanked). Second, the service can include any form of mobile payments (including retail payments and bill payments, among others), domestic or international transfers, and accounts can be accessed by phone. Third, mobile money can be transferred through transaction points that are mobile agents such as bank branches, retailers, and shops.

Mobile money services mainly consist of various types of transactions including peer-to-peer money transfers, bill payments, government payments, retail payments, and allowing for deposits or withdrawals at the agent location. These mobile money services offer numerous benefits such as reducing transaction costs, improving financial inclusion (especially for the unbanked), increasing convenience and speed for consumers, creating opportunities for employment and investment for businesses, and improving the transparency of transactions (and thus contributing to money laundering and corruption reduction.

The formal financial system has excluded many people from access, limiting the scope of such financial services. With mobile money, however, financial transactions can be performed securely, efficiently, and affordably – and customers are able to access their accounts easily and carry out financial transactions flexibly. Besides, mobile money service providers may offer job prospects and reduce the unemployment rate, thus stimulating economic growth. According to ICT News, mobile money may boost Vietnam’s economic growth by 0.5 percentage points.

Despite the importance of mobile money, there still exist possible risks concerning this service, mainly related to potential fraud. The most common types of fraud associated with mobile money include identity theft, fake currency deposits, scams (mobile insurance scams, promotional scams, and so on), and phishing, exacerbated by the abundant use of SIM cards. However, these illegal activities can be prevented through the implementation of regulations to minimise and manage risks while still progressing towards business objectives.

The regulations should be centred around verifying customer identity, monitoring of transactions, raising awareness concerning fraud, and involving law enforcement when necessary. Second, customer money may suffer losses due to abuse by mobile money providers. Third, there also exist distribution risks which are related to third parties as agents which may not have sufficient capacity, expertise, or even capital. Finally, customer privacy and cybersecurity could be another risk which needs to be minimised.

Global mobile money potential

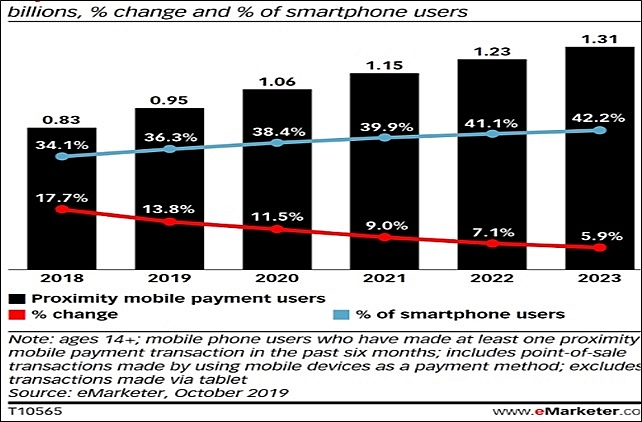

Currently, mobile money is being increasingly used worldwide due to its accessibility and convenience, with approximately one billion mobile payment users worldwide in 2020, 38.4 per cent of whom use smartphones. By 2023, there could be 1.3 billion mobile payment users with 42.2 per cent having smartphones, growing at about 8.4 per cent per year (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Number of users of mobile payments and smartphones in the world |

Vietnam's mobile money potential

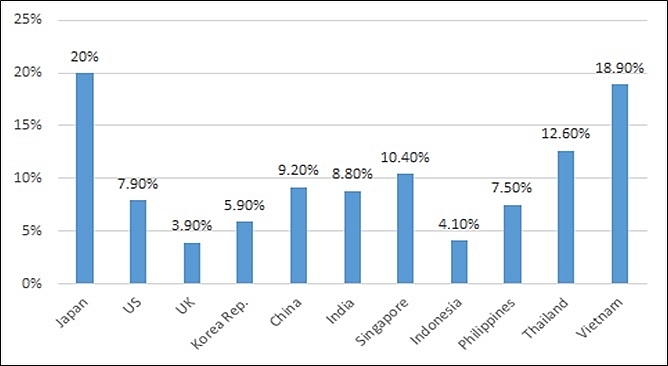

In Vietnam, mobile money is still considered a relatively new service, but shows great potential for future development. First, Vietnam is still a cash-based society, with the proportion of cash in circulation to GDP quite high (18.9 per cent in 2018) compared to regional peers (Figure 2). Under the plan on non-cash payments in Vietnam in 2016-2020 approved by the Prime Minister, the ratio of cash in circulation would be reduced from 12 per cent in 2016 to below 10 per cent by the end of 2020.

|

| Figure 2: Cash in circulation in Vietnam and peers (per cent of GDP 2018) |

Second, according to the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV), 63 per cent of Vietnamese adults possess a bank account (this ratio in Vietnam as indicated by the World Bank was only 40 per cent at the end of 2017), yet in 2019, the number of phone subscribers have reached 129.5 million, with 55 per cent owning smartphones in 2019 – figures on par with Malaysia, and higher than Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, according to E-Marketer.

The growth rate of internet users has also increased significantly over the past years, from 5 per cent of the adult population in 2005 to 70 per cent in 2019 (according to Internetworldstats.com). This presents a desirable opportunity for mobile money services to develop in Vietnam.

Furthermore, the infrastructure required to deploy mobile money in Vietnam has been improving. At the moment, VNPT and Viettel have been granted licenses by the SBV to carry out such services. The national personal database has also been built for issuing personal identification numbers to the people and (somebody is also adopting e-KYC (electronic Know-Your-Customers) soon.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Vietnamese government has required the SBV to expedite research and the use of mobile money to reduce cash transactions.

However, there remain several obstacles regarding the implementation of mobile money services in Vietnam. The potential risks are basically similar to those indicated above. In addition, it will take time for people to give up cash. An adequate database and cybersecurity are also big concerns. A legal framework is now being built but it might very well be a long time in coming, given the service is quite new in Vietnam. Finally, these services may be used for gambling or money laundering purposes if appropriate regulations are not in place.

In consideration of the risks and obstacles, I would like to offer some recommendations to aid the development of mobile money in Vietnam. First, there needs to be a detailed roadmap and deployment plan, as mobile money is relatively new to Vietnam with many uncertainties. This plan needs to clarify the scope and objectives of the project, timeline of implementation, means of co-operation among various stakeholders, and responsibilities of related parties and authorities.

Second, there is an urgent need for a legal system governing these services which covers key aspects, such as creating a fair playing field between banks and non-bank providers, protecting customer’s monies, ensuring transparency and cybersecurity, and preventing and minimising money laundering and gambling, while at the same time ensuring adequate capacity on the side of service providers, outlining selection criteria for agents, and clarifying supervision mechanisms.

Third, the infrastructure and technology need to be consolidated in areas of concern, including things like 4G and 5G, to ensure the service delivery to customers to be satisfactory. The national personal database also needs to be completed and updated, and an ecosystem be created for stakeholders’ benefits.

Fourth, the human element is essential in the growth of mobile money services. At service providers (especially non-bank units), there needs to be a panel of experts and staff with intensive training; extensive training programmes should also be offered to current and potential employees considering the constant exposure to larger cash flows. Customers should be given adequate information and educated on use and risk management, especially those who live in remote areas and have little experience with cashless payments. In this case, “mobile financial education” could be applied. There should be some incentives to promote cashless transactions and increase its accessibility to the wider population as was done in Thailand.

Finally, adequate regulation and supervision of service providers and agents should be conducted to ensure a smooth, convenient and safe process.

In conclusion, mobile money is an emerging trend and holds great potential for development in Vietnam. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, it is time for Vietnam to get the service started. A detailed plan for implementation should be compiled and trust needs to be built and preserved, as keys to success.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Tag:

Tag:

Related Contents

Latest News

More News

- Private capital funds as cornerstone of IFC plans (February 20, 2026 | 14:38)

- Priorities for building credibility and momentum within Vietnamese IFCs (February 20, 2026 | 14:29)

- How Hong Kong can bridge critical financial centre gaps (February 20, 2026 | 14:22)

- All global experiences useful for Vietnam’s international financial hub (February 20, 2026 | 14:16)

- Raised ties reaffirm strategic trust (February 20, 2026 | 14:06)

- Sustained growth can translate into income gains (February 19, 2026 | 18:55)

- The vision to maintain a stable monetary policy (February 19, 2026 | 08:50)

- Banking sector faces data governance hurdles in AI transition (February 19, 2026 | 08:00)

- AI leading to shift in banking roles (February 18, 2026 | 19:54)

- Digital banking enters season of transformation (February 16, 2026 | 09:00)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version