Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure poised to win out on TPP

|

By Michael Sieburg Michael Sieburg is an associate partner at Solidiance Vietnam and the author of the “Trans-Pacific Partnership: A Boost for Vietnam’s Manufacturing Growth” white paper. Solidiance is a corporate strategy consulting firm focused on Asia. The firm advises CEOs on deals, define new business models, and accelerate growth in Asia. Solidiance’s expertise is focused on industrial applications, green technology, and the healthcare and technology sectors, with offices in 12 different Asian countries, including Vietnam. |

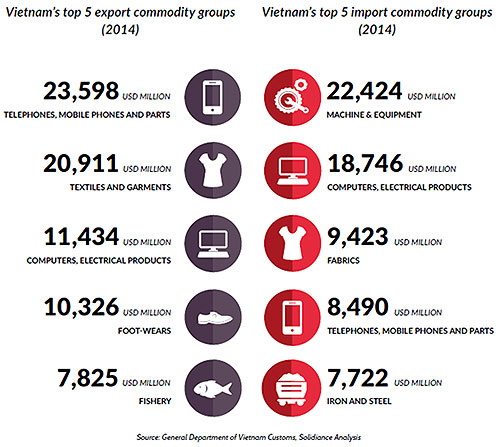

Driven by already growing trade volumes, a competitive manufacturing environment, and tariff cuts to key products, such as electronics, textiles and garments, trade growth is expected to accelerate further by at least 11 and 13 per cent year-over-year for exports and imports, respectively.

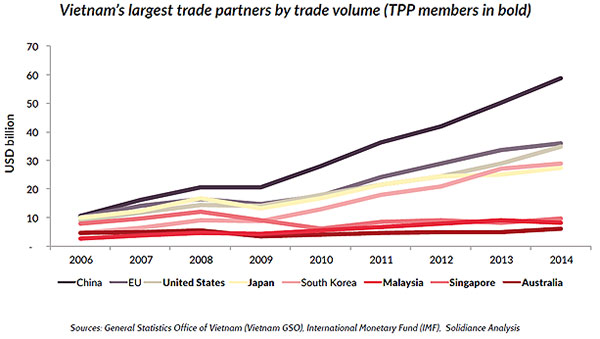

A recent study by Solidiance highlights that while China remains Vietnam’s largest trade partner, the TPP’s ratification will lead to higher manufacturing-driven trade volumes with the US and Japan, potentially resulting in an additional export value of $68 billion by 2025. As a result, Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure will benefit from the TPP as investments targeting its upgrade will be needed to accommodate the rising flow of goods.

Current state of Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure

Spanning more than 3,200 kilometres along the coastline, Vietnam is the among the smallest TPP members geographically, only surpassing Brunei (161km of coastline), Singapore (193km), and Peru (2,414km). Vietnam hosts approximately 115 seaports, including Saigon, Haiphong, and Danang, which are among the largest. Of the three, Saigon Port has the highest storage capacity, Haiphong has the longest birth capacity, and Danang has the highest maximum vessel size. Despite being the largest, Saigon Port’s volume in 2013 was only 5.96 million twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEUs), which was roughly half of Malaysian Port Kelang’s volume, 10 per cent less than Malaysian Tanjung Port’s volume, and around 18 per cent of Singapore’s overall port volume. This suggests a demand for higher capacity alone, relative to other member states, especially since maritime transport is the predominant mode of facilitating trade between Vietnam and other countries.

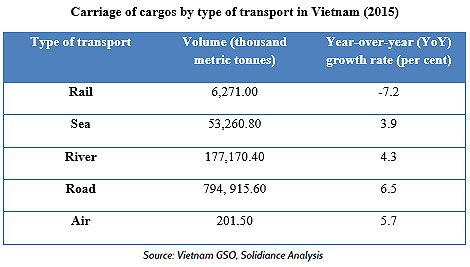

Once containers set anchor in Vietnamese ports, road transport is the primary medium for carrying freight, where goods are transported mainly from north to south, from ports to factories and warehouses, and vice versa. A shortage of smartly-designed road capacity and road access to ports remain the key barriers for improved efficiency, leading to higher logistics costs and decreasing global competitiveness - not just in transportation infrastructure, but ultimately in manufacturing, as well.

Although air freight accounts for a relatively small amount of Vietnamese trade volume, a quarter of the domestic trade value is shipped by air and Vietnam is expected to be among the world’s fastest-growing air cargo markets in the years ahead, expanding at 6.6 per cent per annum, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). Rail transport, on the other hand, is currently underdeveloped and will need upgrading.

At present, cargo handling facilities, such as logistics centres, are run by the private sector, with standalone warehouses located near ports, airports or industrial zones to promote business efficiency. The Vietnamese government recently approved a development plan for logistics centres, where each region will have one dedicated centre serving local airports and ports.

As logistics competitiveness is highly dependent on a country’s transportation infrastructure, Vietnam will move to upgrade itself in order to maximise benefits from the trade agreement. Key investments will likely target the port network’s limited capacity, including the minimum vessel size allowed and storage capacity, underdeveloped road and rail infrastructure, and limited forwarding centres and supply services, which ultimately drive logistics costs higher as more vehicles carry less cargo to further distances.

Opportunities for multinational logistics companies through the TPP ratification

Accounting for about 40 per cent of Vietnam’ GDP, the trade industry has been the main driver for investments as well as international transport and logistics services, even prior to the TPP. The further opening of Vietnam as a market translates to a greater need for transporting, supplying, and warehousing at international standards, thereby leading to the development of logistics services and investments in warehouses, especially at large ports.

Road infrastructure improvements are already underway and links are being created between manufacturing regions and product destinations. However, to accelerate upgrades, the government announced in January 2016 that it would turn to the private sector for additional infrastructural funding, due to constraints on the state budget. This is a result of an estimated $48 billion infrastructure budget requirement from 2016 through 2020 that has been identified to support and sustain the country’s economic growth, which has been among the highest in Asia in the recent years. This governmental move will create a more conducive investment environment, aimed at encouraging private and foreign investment in infrastructure projects.

Following Vietnam’s 2007 accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), many global logistics companies have strengthened their presence in the country, as the sector shifted towards a more liberal market. The expansion of multinational companies in Vietnam to create a more competitive market is driving growing demand for supply-chain management facilities, particularly in relation to handling more complex sourcing issues, production requirements, and servicing sales networks.

In order to successfully access the Vietnamese logistics market, the best move forward would be to develop the industry from the inside as well, rather than simply relying on external drivers. Foreign logistics companies, for example, may collaborate with local partners in training and technology transfer to likewise maximise their operations through increased localisation. They may also facilitate freight forwarding and third-party logistics service-providers (3PLs) to boost business competitiveness and they can make good use of geopolitical advantages in developing a logistics infrastructure in deep-water ports, international airports, trans-Asia railway, as well as logistics centres to accommodate the trade demands of the TPP.

Hence, while improvements are still needed to facilitate growing trade volumes, Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure will inevitably benefit from the TPP as a result of the aim to boost Vietnam’s competitiveness. This will increase the country’s attractiveness as an investment hub, developing both the manufacturing and logistics sectors hand-in-hand.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- Mitsubishi Estate launches Logicross Hai Phong - a milestone in logistics evolution (November 20, 2024 | 14:32)

- Semiconductor workforce partnerships deliver industry-relevant training (November 20, 2024 | 10:58)

- German Quickpack to invest $31.7 million in Long An province (November 20, 2024 | 09:31)

- Foreign-invested enterprises drive logistics investment in the southeast region (November 20, 2024 | 09:27)

- Chile visit underscores trade benefits (November 19, 2024 | 10:00)

- Trump’s second term impacts sci-tech activities and industry 4.0 technologies (November 18, 2024 | 10:00)

- Vietnam eyes nuclear revival to bolster energy security (November 14, 2024 | 16:46)

- Kyokuyo completes $13.5 million seafood factory in Vietnam (November 14, 2024 | 12:19)

- VinFast receives $3.5 billion funding from Vingroup and Pham Nhat Vuong (November 14, 2024 | 06:38)

- Localities sprint to reach FDI targets (November 13, 2024 | 10:00)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version